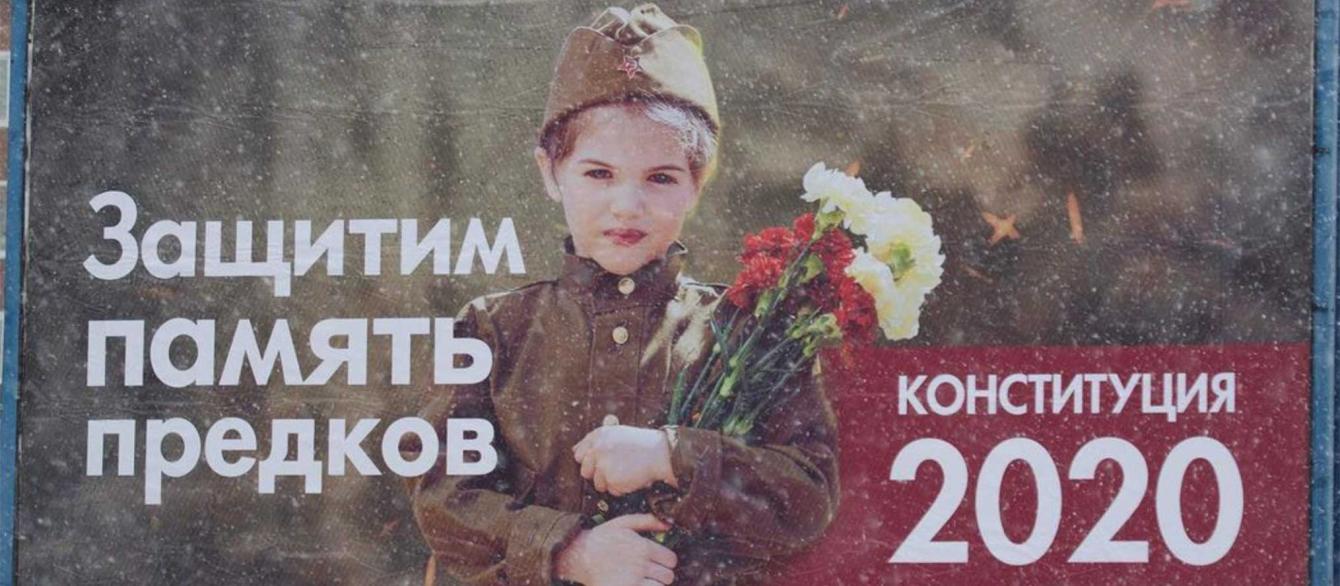

In late March, as Russia prepared for a national vote on constitutional changes that would allow President Vladimir Putin to break through term limits and retain power until 2036, a set of billboards in the Siberian city of Tomsk called on residents to endorse the changes with an unsubtle allusion to the country’s past: A small girl dressed in a Red Army uniform looked down on passing cars and pedestrians, clutching a bouquet of flowers intended as a gift to the country’s revered World War II veterans. “We’ll defend the memory of our ancestors,” read the accompanying message, “Constitution 2020.”

Days after the billboards surfaced online, provoking uproar among Putin’s critics, the president postponed the national vote in a televised address to the nation. The coronavirus pandemic was spreading through Russia, and plans for a spring of political pageantry that would crown him Russia’s undisputed leader and culminate in a grand May 9 military parade marking 75 years since Nazi Germany’s defeat had been scuppered by an invisible enemy against which the country was now forced to mobilize all resources.

The Tomsk billboards surprised few people in Russia; for decades, the state had used memory of the World War II experience as a political tool, and they serve merely as evidence that the practice is alive and well. Victory over Nazi Germany, which cost over 26 million Soviet lives, has emerged as a cornerstone of Russian identity, an all the more cherished story amid the battles over historical truth playing out across Eastern Europe today. In a meeting with war veterans in St. Petersburg this January, Putin promised to “shut the filthy mouths” of those who falsify history and fail to give the Soviet Union its due. Per the constitutional changes he initiated and endorsed, Russia is a country that “safeguards defense of historical truth” and has no tolerance for “belittling the nation’s feats” in fighting fascism. Monuments celebrating Red Army heroes, erected across Eastern Europe after 1945, are being dismantled as Moscow wages a bitter war of words with Prague, Warsaw, and other capitals of its former satellite states, where many see the monuments as symbols of an occupying power. Russia, Putin has repeatedly warned, will accept this no more.

The offensive against competing historical narratives is intensifying in Russia itself. As the country prepares for its Victory Day celebration, it is playing out at sites of memory like Perm-36, a former Gulag, which now houses an exhibition extolling its labor history, and Katyn, where thousands of Polish officers were killed by the Soviet secret police in 1940 and where a controversial new museum extols Russo-Polish ties. In Tver, near Moscow, authorities have ordered the removal of commemorative plaques affixed to a building where many of those Poles were shot by Stalin's secret police, and commenced plans to excavate parts of the site where they lie buried. In Sandarmokh, a forest clearing near Russia’s border with Finland where researchers discovered a Soviet execution site in 1997, a government-backed body is already digging up the bones to test the controversial theory that among the skeletons are hundreds of Soviet POWs executed by Finnish forces that occupied the region during World War II.

A parallel effort aims at enshrining the state-sanctioned story of the Great Patriotic War. Ahead of May 9, grand monuments are ready for unveiling in several Russian cities, and a vast cathedral dedicated to the country’s past military glories has been built outside Moscow. The victory parade on Red Square was meant to feature 15,000 troops and almost 400 vehicles and aircraft, showing off the newest elements of Russia’s arsenal to world leaders including France’s Emmanuel Macron, whose attendance Moscow hoped would lend it legitimacy at a time when it remains under Western sanctions. But the pandemic has upended those plans, with lockdowns ordered across the country and alternative, virtual forms of commemoration planned. If the aim was to seize on the upcoming anniversary to assert Russia’s historical narrative and squeeze out all others, the catharsis—along with Putin’s coronation—may have to wait.