They say a picture is worth a thousand words.

(In case you are curious, this famous adage is attributed to at least half a dozen sources, including a Chinese philosopher, a French emperor, a Russian novelist, and an American newspaper editor.)

Imagine for a minute the adage were true. Next, imagine standing in front of a stack of 3,500 pictures. 3,500 maps, to be precise, all created as part of a series, at the same scale, in the same projection, with the same cartographic style. Reading those maps would be the equivalent of reading three and a half million words or eleven thousand densely-packed pages, all variations on a theme laid out in black and white. Would you be up to the task?

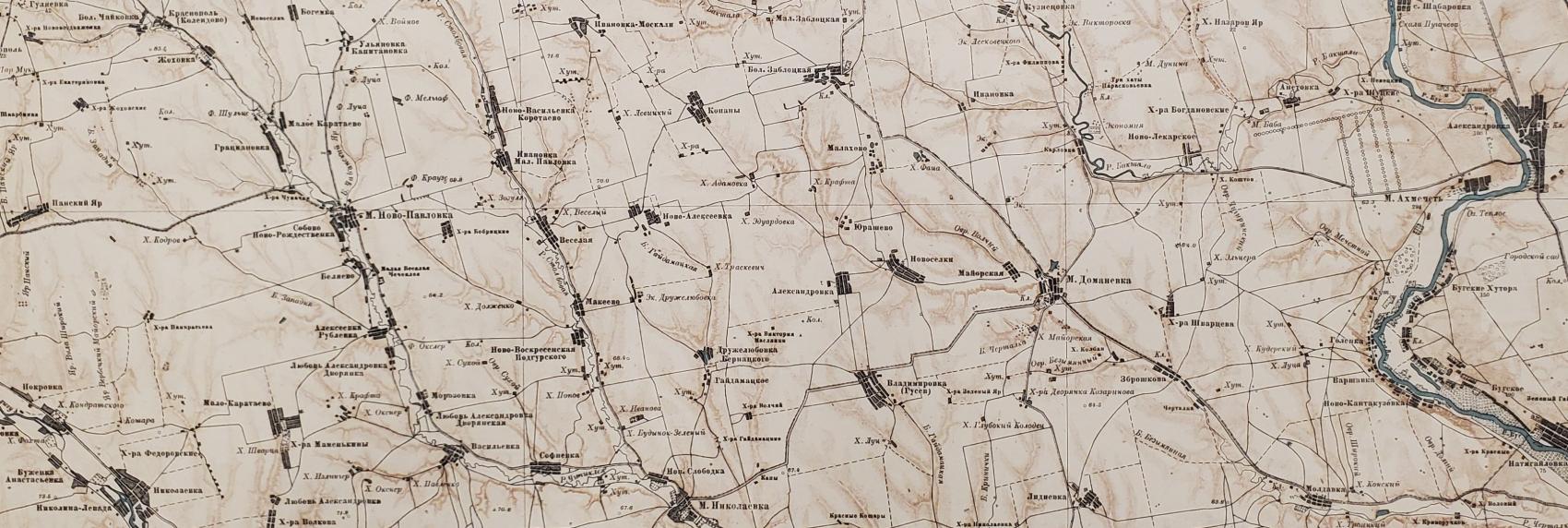

It just so happens that a trove of maps that size rests in the basement of the James Madison building of the Library of Congress, stacked on twenty-five wide shelves. They were produced as part of the Military-Topographic Survey of European Russia in the second half of the 19th century and hold a wealth of detail about land use, water resources, roads and rails, and demographic distribution. They speak volumes about the structure of space in the tsarist empire.

Detail from the index grid of the survey of European Russia.

The existence of the maps is no state secret and there are copies in various quantities in libraries across Russia and Europe. But because their stories are coded in the language of lines, grids, hachures, and shading, rather than sentences and paragraphs, they have remained on the edges of historical study. Those who make it their business to know the history of the Russian Empire know they are there, but not what to do with them.

We decided to read them.

The Russian Military-Topographic Depot set about the large-scale topographic mapping of the empire in 1846.The Depot was abolished and reformed as the Military Topographic Section of the Directorate of the Russian Army General Staff in 1863. Although the main survey and cartographic work was completed by 1863, this truly was a project with no end: surveyors continually dispersed through the provinces improving triangulations and collecting data, cartographers made edits, engravers prepared new printings and new editions. Within that larger initiative there were several smaller projects, including the mapping of European Russia. The maps produced as part of that project were oriented to the Pulkovo meridian (the longitude of the Pulkovo Observatory in 1839 near St. Petersburg) and executed at a scale of 1:126,000 (1 centimeter = 1,260 meters).

Topographic surveys could make or break an empire's reputation.

The project was uniquely Russian in content and utterly trans-imperial in form. The middle of the nineteenth century was the golden age of topographic mapping, with grand projects conducted by the British (in England and south Asia), the French (in France and north Africa), and the Americans (in the western U.S.). As Matthew Edney has shown, these projects and others like them launched because of a tectonic shift in the way people thought about maps and mapping. Around 1800, “the privileged form of mapmaking ceased to be the rational process of combining various observations and itineraries within a framework of latitude and longitude and became the directly observed and measured survey.” This shift from “low-resolution abstraction” to “high-resolution” triangulation could only be made by states with sufficient expertise and resources. In fact, as the nineteenth century progressed it became clear that the world could be divided into states that could, and states that could not, produce “ideal” maps.Matthew H. Edney, “The Irony of Imperial Mapping,” in James Akerman (ed), The Imperial Map: Cartography and the Mastery of Empire (University of Chicago Press, 2009): 41. Topographic surveys could make or break an empire's reputation.

The Military Topographic Survey of European Russia was therefore a demonstration of imperial power. It was the magnum opus of state mapmaking.

Detail from row XXVIII column 9, printed in 1917. The map shows the right bank of the Southern Buh River just north of Voznesensk in the Mikolaiv district of Ukraine. The village of Akhmechet (М. Ахмечеть), shows on the right, dates back to Ottoman times and was renamed Pribuzhzhya (Прибужжя) in 1946.

In the middle of the nineteenth century there were 59 provinces in the “European” part of the empire (if we include Poland and exclude Finland, which is what the topographers did). The survey divided this area into 509 pieces. It imposed a systematic grid and assigned row and column numbers to each rectangular piece of the puzzle. Printed maps began appearing in the 1870s, each capable of covering a kitchen table and showing an area of roughly 1,500 square miles – the size of Rhode Island.Each sheet measures approximately 64 centimeters wide and 50 centimeters long with the neatline set a few centimeters from the edge of the paper. Gridlines mark every twenty minutes of longitude and latitude. Reprintings and new editions appeared at uneven intervals on either side of the First World War and the revolutions of 1917, occasionally in German and Estonian as well as Russian.

The strategic value of these large-scale maps was not lost on anyone, least of all the U. S. Army. While the maps in the Library of Congress collection took various (often dramatic) routes from St. Petersburg to Washington over the first half of the twentieth century, many arrived thanks to the efforts of the Army Map Service. The Army Map Service - we will have much more to say about this in a future post - regularly deposited pallets of material with the library, and the Map Division opened its figurative arms, accepting as much as it could store. As a result, we have not 509 sheets at our disposal, but seven times that number.

The library has taken meticulous care of this particular mountain of maps, but it has never found it necessary to create a full inventory. That is where our project began. Over the past few months, Imperiia research assistant Charles Pflieger took up residence in the Map Division. With the unflagging support of the librarians there, he assessed every sheet, documenting print dates and repository stamps, recording rips and tears and the odd marginal doodling, so that we can create a high-quality composite of the 19th century survey. It is the sort of task you would only accept if you were sure the result was worth it.

Charles and I are sure. After all, this maddening assortment of copies and editions is the key to visualizing the archive of the late imperial period. The data we harvest from it will allow us to map European Russia at a scale and with a level of accuracy that has not been possible before. This is a multi-phased project that involves everything from image processing to compiling a historical gazetteer.

We are ready to begin sharing notes from the field. After all, if a picture is worth a thousand words, we have quite a few stories to tell. Stay tuned.