Functional Beauty

In early 1914 the Baedeker publishing company issued the first English-language edition of Russia with Teheran, Port Arthur, and Peking: Handbook for Travellers. The world was on the edge of war and the tsarist empire was careening toward collapse, but no one quite knew that yet. Well-heeled Europeans were still paging through their trusty Baedeker guidebooks, contemplating walking tours of China, rambles in the Alps, and train rides through Russia.

The Handbook for Russia contains 88 itineraries which pass through over 3,000 places—towns and villages of all shapes and sizes. It describes mountains and caves, rivers and churches, cafes and ruins. It contains no pictures and tells no stories, yet in its own way it charts the landscape of the Russian Empire.

Panorama of Riga, early 20th century

The Baedeker itineraries describe routes through eight reigons: I. General Government of Warsaw (Poland), II. Western Russia (Baltic provinces), III. St. Petersburg and Environs, IV. Grand Duchy of Finland, V. Central and Northern Russia, VI. Southern Russia, VII. The Caucasus, and VIII. Teheran, Railways in Asiatic Russia, Port Arthur, Peking.

Dozens of enviable maps and plans support that work, but the Handbook relies less on them and more on the art of the itinerary. At its simplest, an itinerary is nothing more than a listing of places in sequence—a tool for moving from origin to destination.

Like many of the world’s most powerful technologies, the beauty of the itinerary is in function rather than form. If an itinerary tells you exactly what you need to know with absurd efficiency and utter predictability, it is a beautiful thing.

The Baedeker itineraries meet this threshold and then some. They digest the vast chaos that was the Russian Empire and return it, streamlined and simplified, in the form of neat paths along railway lines and carriage routes. From starting points in London, Berlin, and Vienna, they run along arteries with endpoints in Warsaw, Helsinki, Odessa, Astrakhan, Tashkent, and Vladivostok (with Tehran and Beijing thrown in for some extra-imperial fun). There are sidetracks and alternate routes, and occasionally itineraries overlap, but for the most part the reader—and would-be traveller—has the sense of linear movement through an exquisitely well-defined space.

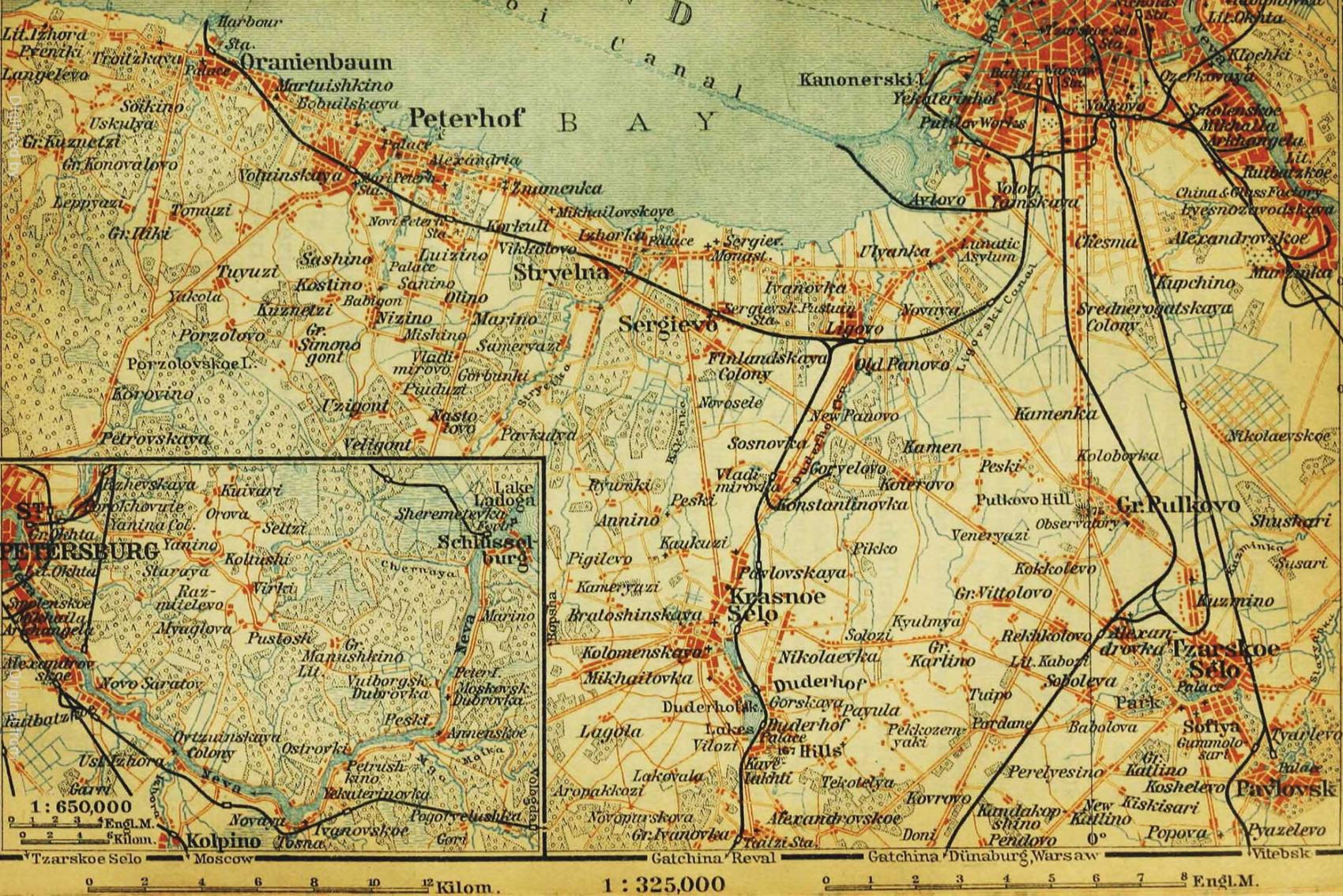

"The Nevá from Schlüsselburg to St. Petersburg." Cartography by Heinrich Wagner and Ernst Debes. Published in Leipzig by Karl Baedeker, 1914.

I stumbled across the Handbook last spring. I bought a copy and have kept it on my kitchen table (i.e., my desk) ever since. I have read it in its entirety, though not from cover to cover. I am teaching with it. Lecturing about it. Tweeting my takes on its humor and wit. I am even using it as the foundation for my own “Guidebook” project.

The Handbook has a firm grasp on me because it offers me something I treasure as a human being, as well as something I require as a historian.

The thing I treasure is a visceral sense of the past.

That might sound a bit counterintuitive. But as much as I value Baedeker’s logic and the geographic information system that girds it, I crave the guidebook’s digressions into sound and flavor. They allow the places of the empire to come alive.

Let me give you just one example. The Handbook devotes a hundred pages to St. Petersburg, and they are brimming with impeccably organized notes on the arrangement of the Hermitage galleries and the iconography of the cathedrals.

But what stopped me in my tracks was the description of the calls of street vendors hawking everything from pasties to dressing-gowns. Here the editors don’t bother listing prices or offering advice on how to procure quality goods. They simply record a litany of cries: “tzvyeti, tzvyetotchki” (flowers)! “okuni, yershi, sigi, lososina, ruiba zhivaya” (perch, ruff, char, salmon, live fish)! “apelsini, limoni, khoroshiye” (tasty oranges and lemons)!

Baedeker’s transliterations follow the standards of the Royal Geographical Society rather than the Library of Congress, but otherwise, if you have spent time in Russia, those cries will be familiar. You will hear the cadence and intonation. You will sense the street as I do, singing from the page into your ears.

The thing I require as a historian is a way into the story.

As a historian, sometimes you go in, well-armed and confident, from the roof; sometimes you dig a grubby tunnel into the cellar and hope for the best. It is impossible to know how much damage you will sustain or when you will emerge. But the story is always there.

There are endless stories to tell about the Handbook, but I thought I would share one that sheds some light on the practice of history, the relationship between books and machines, and the very real value of research.

(I should warn you that this story is the product of an episode of cellar-clambering.)

Here is the way in.

The Volga Voyage

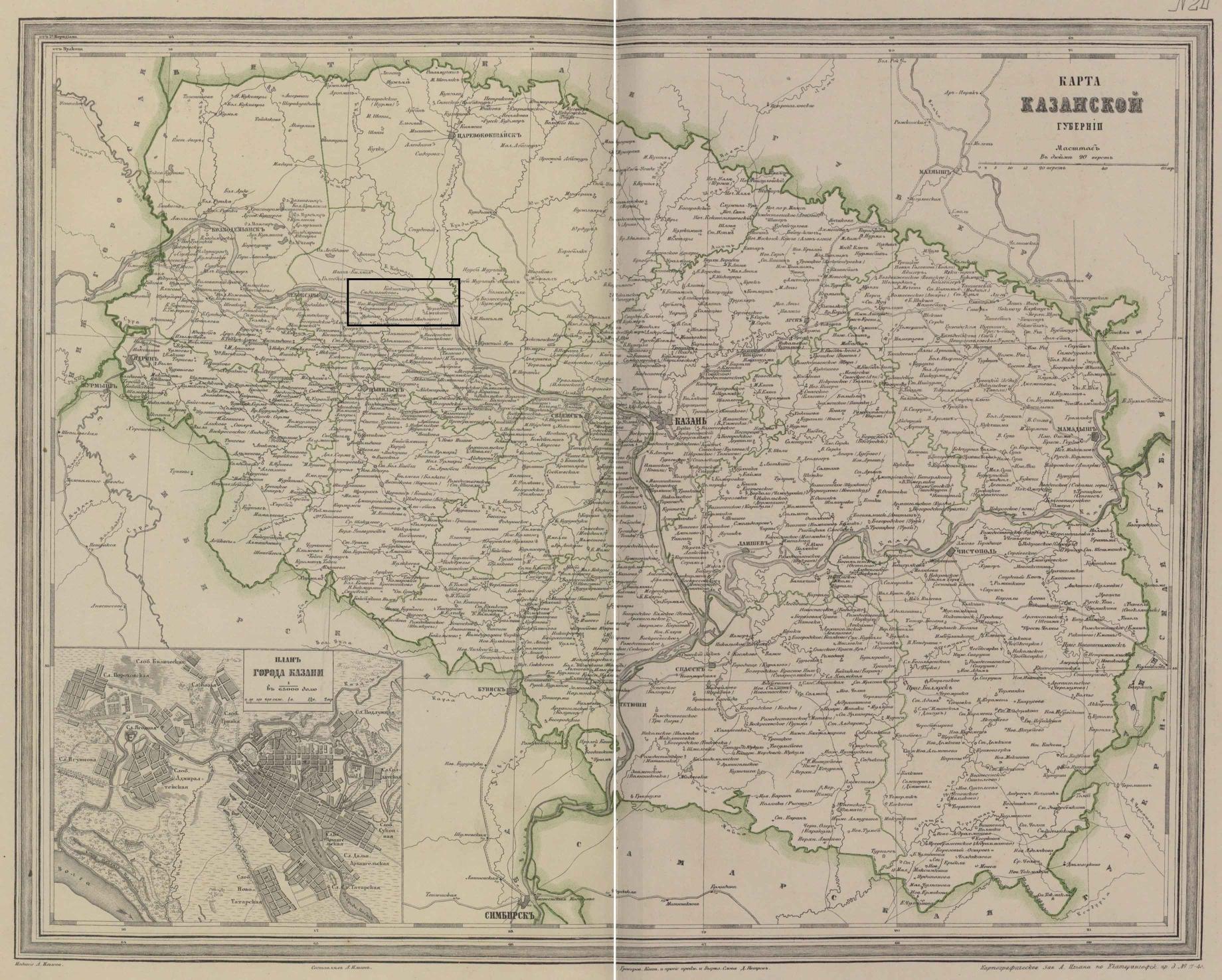

The section of Baedeker’s Handbook on “Central and Northern Russia” contains an itinerary for a voyage down the Volga departing from Tver and passing Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan, and Samara on its way to Syzran. Even someone who does not suffer from an obsession with rivers (as I do) might gravitate here. A voyage. The mighty Volga. Slightly exotic-sounding waypoints.

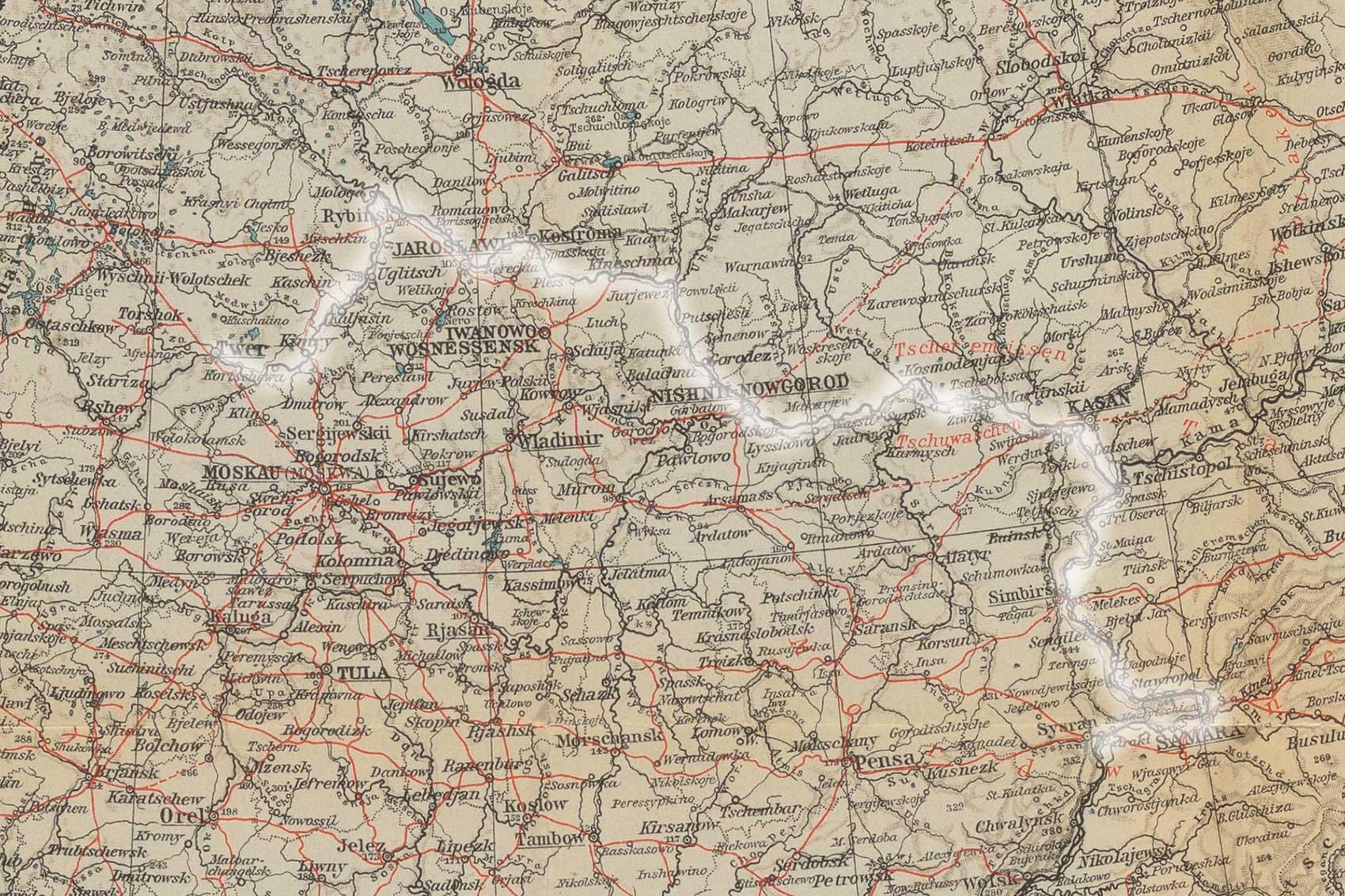

Detail of The General Map of Russia, Heinrich Wagner & Ernst Debes (cartographers). The white line highlights Route 45 of the Baedeker Handbook: the Volga voyage from Tver to Syzran.

By the middle of the 19th century, the Volga was known to be 3,295 versts (2,184 miles) long. The route from Tver to Syzran covered just a portion of that. As part of my project I have been recording the waypoints along each itinerary and mapping them. I am fixing them to the coordinates of their modern equivalents (to the coordinates of the centroids of their modern equivalents to be very precise) using the GeoNames database—the gold-standard open-source world gazetteer.

Among the 60 waypoints along the voyage to Syzran, there is only one that does not turn up—after the usual modest wrangling—in GeoNames.

Well, to be more precise, there is only one waypoint that turns up in the wrong place.

To be even more precise, there is one waypoint that turns up in eight places, none of which is correct.

According to Baedeker, the place is called “Sunduir.” If we shed the archaic transliteration system of the Royal Geographical Society, which was in common use in the early 20th century but causes us to furrow our brows, we can call this place Sundyr’.

The Handbook describes Sundyr’ as a "a market town situated on the slope" of the right bank of the Volga between Cheboksary and Kozlovka, 289 versts from Tver.

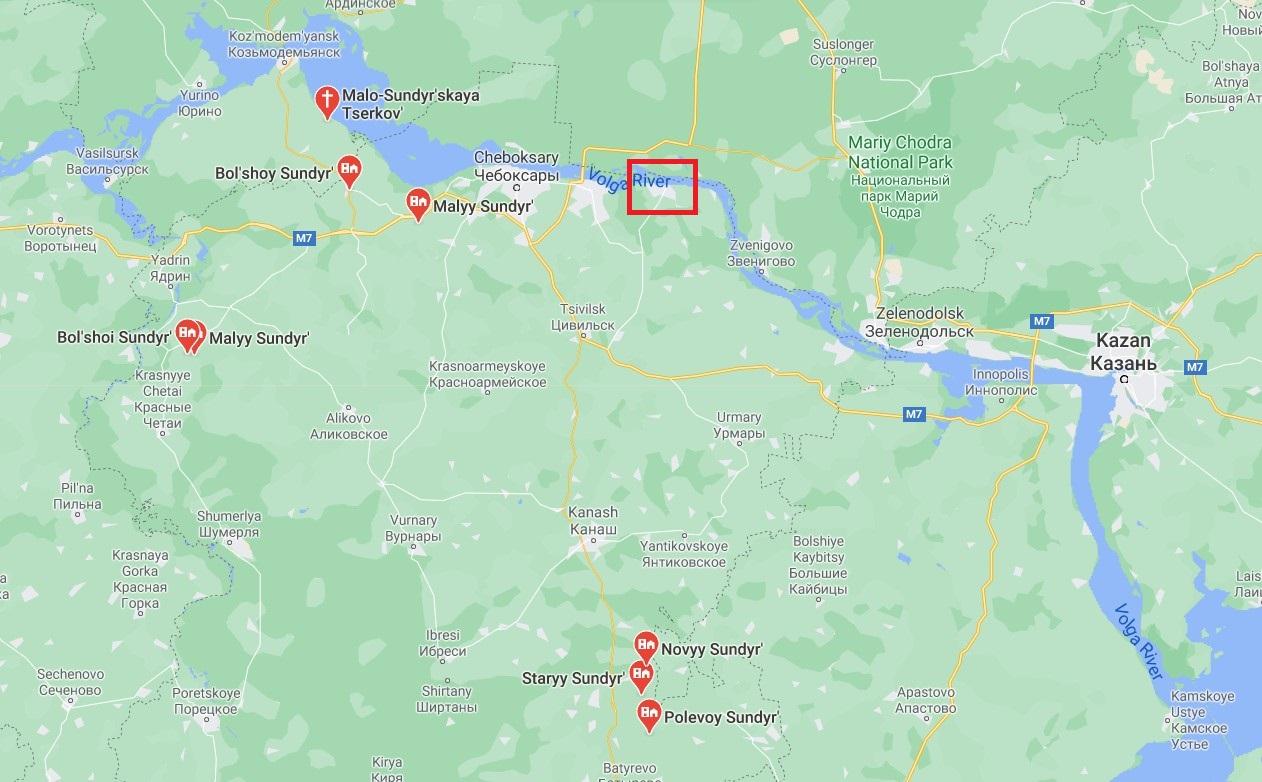

Fair enough. GeoNames has heard of "Сундырь." It associates "Сундырь" (Sundyr') with eight populated places (and two streams, to boot). It knows about Malyy Sundyr’, Novyy Sundyr’, Staryy Sundyr’, Polevoy Sundyr’, and Bol’shoy Sundyr’—all of which are west or south of Cheboksary instead of east, and only two of which are on the bank of the Volga.

Locations of places named Sundyr' (according to Google Maps), with the location of the Sundyr' that became Mariinsky posad marked with a red rectangle.

Clearly, either two of the best modern geographical databases are wrong, or the venerable Baedeker publishing house is wrong.

Either that, or they are both right.

Gazetteers (databases that associate placenames with location information) like GeoNames and Google Maps are extraordinarily good at recognizing historical places by their contemporary names. They cope remarkably well with alphabets, alternate transliterations and the occasional misspelling. They are able to equate Volgograd (modern placename) with Stalingrad (as it was called from 1925 until 1961) and Stalingrad with Tsaritsyn (as it was known prior to 1925). They know that whether a user asks for St. Petersburg, Petrograd, or Leningrad, they will likely be content with the same coordinate pair.

They are able to do this not because machines are brilliant, but because they have been fed incredible amounts of data by (occasionally brilliant) human beings.

The Document Dive

What they can’t do, on the fly, yet, is conduct historical research.

Solving a problem to which Google has no solution, or providing a piece of information that algorithms cannot generate, is the sort of thing that sets me dashing to brew a fresh pot of coffee and get to work. Because as any decent historian knows, there are answers to be found if you know where to look.

The first place I looked to find the “right” location for Sundyr’ was the Geographical-Statistical Dictionary of the Russian Empire (1863–1885).

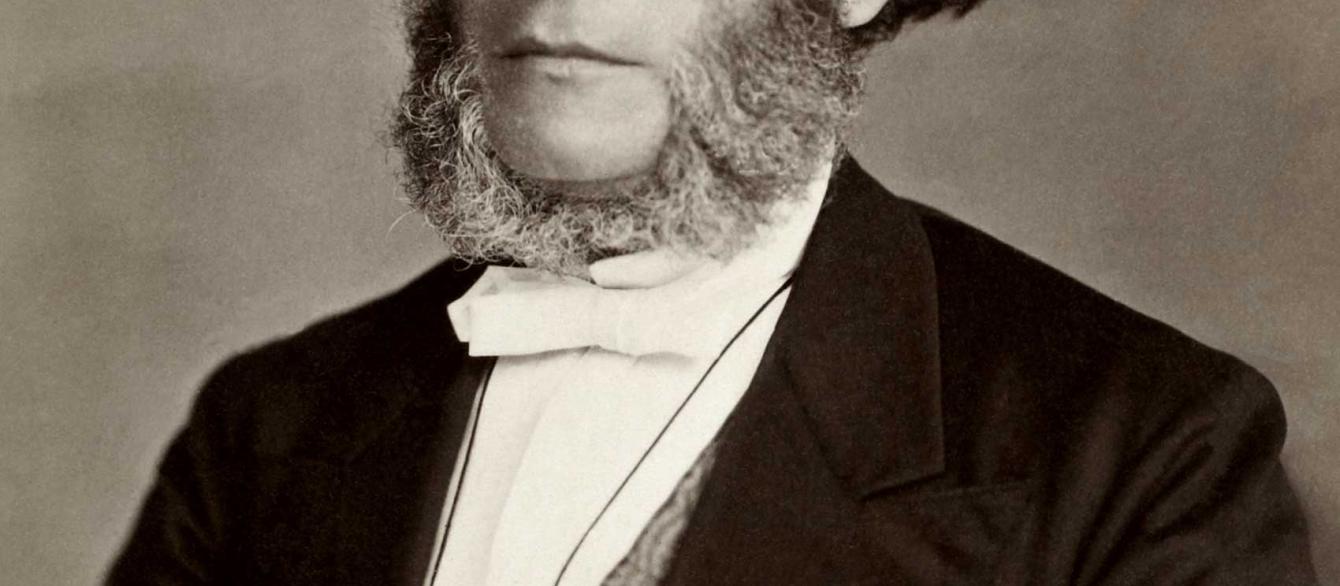

This dictionary was quite the thing in its day. It was the brainchild of Pëtr Petrovich Semënov-Tian-Shansky, the spectacularly bearded and slightly rebellious collector of insects and Dutch art who directed the Imperial Russian Geographical Society for four decades.

If you do not already have a copy on your bedside table, I highly recommend getting your hands on all five volumes. (Of course, living in imperial Russia and having disposable income would make the purchase easier. Otherwise, access to Google Books will do the trick.)

I am happy to report that volume 4, published in 1873, contains a reference to Sundyr’. The entry says—can you stand the suspense?—“see Mariinsk.”

Which I did, dutiful scholar that I am.

“Mariinsk” is in volume 3, which was published in 1867. The entry is long and interesting to someone obsessed with historical geography. And I will summarize it for you.

The Dictionary agrees that Sundyr’ was a market town on the right bank of the Volga, 24 versts east of Cheboksary and 114 versts west-south-west of Kazan. In other words, the Dictionary places it exactly where Baedeker suggests a traveler would find it.

But it has much more to say, in large part because Sundyr’ had been there since at least 1620. By 1624 it included the Holy Trinity Church, a residence for the (Russian Orthodox) metropolitan, and a brewery. When Empress Catherine II secularized church lands in 1764, Sundyr’ became property of the state: a collection of six villages and settlements whose occupants engaged primarily in trade and cottage industries rather than agriculture.

Eventually, some of those occupants petitioned to convert the settlement—and its inhabitants—from rural to urban status, and in 1856 Tsar Alexander II agreed. The conglomeration of villages that for centuries had been Sundyr’ became “Mariinsky posad” in honor of the new empress, Maria Aleksandrovna.

Within a decade of the name change the population of Mariinsky posad—nearly 3,000 strong—lived among three Orthodox churches, ten stone houses, dozens of shops and warehouses near the pier, 4 (water)mills, half a dozen schools, and a tavern. Farming had taken hold. Fishing held its own. A great many men worked on the ships sailing between Mariinsky posad and Astrakhan. There were dozens of coopers and even more blacksmiths, and local pilots could earn over 100 rubles for a single passage to (or from) the Caspian Sea.

Caravan with grain.

River trade at Mariinsky posad / Sundyr' amounted to over a quarter million poods (4,000 tons) and was valued at nearly 40,000 rubles per year.

The posad’s location at the confluence of the Volga and Kokshaga rivers was not coincidental: grain poured down the Kokshaga River from Simbirsk. Timber, wooden goods, and sterlet flowed from surrounding districts. By the end of the 19th century, Mariinsky posad had added a hospital and two fairs, and the population had nearly doubled.

In other words, “Sunduir” was no sleepy backwater. It was a bustling place. It was everything one might expect of a thriving river town.

Except that, in 1914, it did not exist.

The Leipzig Puzzle

Let’s return to that story.

In 1856, Alexander II wiped Sundyr’ off the map. But the name lived on. Reports published by the Ministry of Internal Affairs continued to describe “Mariinsky posad Sundyr'” for decades. Popular atlases such as the Detailed Atlas of the Russian Empire (1871) and the landmark Brokgauz-Efron Encyclopedia followed suit, appending the old toponym to the new. And as we know, the most celebrated geography of the Romanov period included entries for both Mariinsky posad and Sundyr’.

Is it surprising that a new placename failed to wholly supplant the old one? Even after half a century?

It is not.

Is Sundyr’ the only place in the empire where traditional toponymy persisted in the face of imperial decree or where two utterly different toponyms were used almost interchangeably to describe the same place?

Absolutely not.

Is it curious that the juggernaut of geographical information that was the Karl Baedeker publishing house called this place by its old name, as if the name “Mariinsky posad” had never been conjured?

It is.

Why?

Maybe word simply failed to reach Leipzig that this robust-but-unremarkable Volga town had changed its name. Is that so hard to believe?

It is, actually. Because the Baedeker house prided itself on providing readers with the most accurate information, year after year, edition after edition.

The first edition of the Russia guide was published in 1883 in German, followed by several more German and French editions before the English-language edition saw the light of day in 1914. The man at the helm throughout this period was Fritz Baedeker. He had taken his place in the family business alongside his brother Karl (son of the original Karl) and was in sole control by 1877.

It was Fritz who moved operations from Koblenz to Leipzig. It was Fritz who developed a crucial partnership with the cartographers (Heinrich Wagner and Ernst Debes) who would lend the guidebooks their signature flair. And it was Fritz who championed the use of crowdsourcing as a technique for acquiring up-to-date information about hotel service, restaurant prices, museum hours, bribery, and bureaucracy. Reports on recent demolitions, fires, and refurbishments seem to have flowed into Leipzig on the backs of ticket receipts and such, because the Handbook contains dozens of these details.

The publishing house also consumed a regular diet of contemporary narrative, historical, and cartographic materials. The “Geographical and Ethnographical Sketch of European Russia” that opens the 1914 Handbook ends with an extensive bibliography of “general information,” histories, works on art and literature, and yes, maps. Special maps of the Caucasus published in Munich. Atlases published in London. Even the topographical series (large-scale) of European Russia published in St. Petersburg at the turn of the century.

Baedeker knew the going rate for geographical information. The editors kept abreast of the market and cultivated the connections necessary to operate in cases where maps were “not procurable through ordinary channels.” As a result, the Handbook gets so many things right. So many small and otherwise inconsequential places are recorded, accurately, on its pages. And when the Baedeker team assembled the itinerary for the Volga voyage—sometime in the early 1880s—nearly every source they could have put their hands on would have told them of the existence of Mariinsky posad. Or possibly Mariinsky posad-Sundyr’. The place was no longer called Sundyr’ and everyone knew it.

Everyone but Baedeker?

Company Interests

As it happens, there was one cohort in Russia that continued to call Mariinsky posad exclusively by its old name: the trio of steam navigation companies sending passenger ships up and down the Volga.

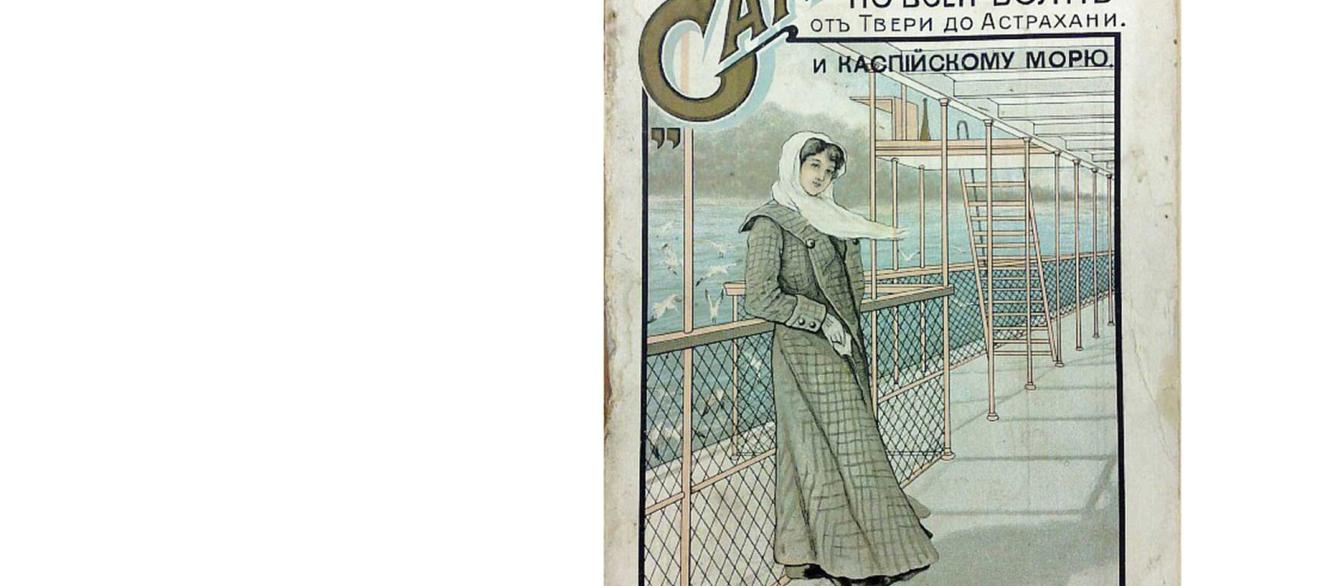

Volga Steamboat Company (established 1843), the Mercury Company (1849), and the Samolet Steamboat Company (1853) had a vested interest in placenames. Their businesses depended on the ability of customers to identify waypoints and the routes between them, and on their own ability to grow the customer base. In a burgeoning industry charged with excitement but rife with risk, continuity and predictability had value.

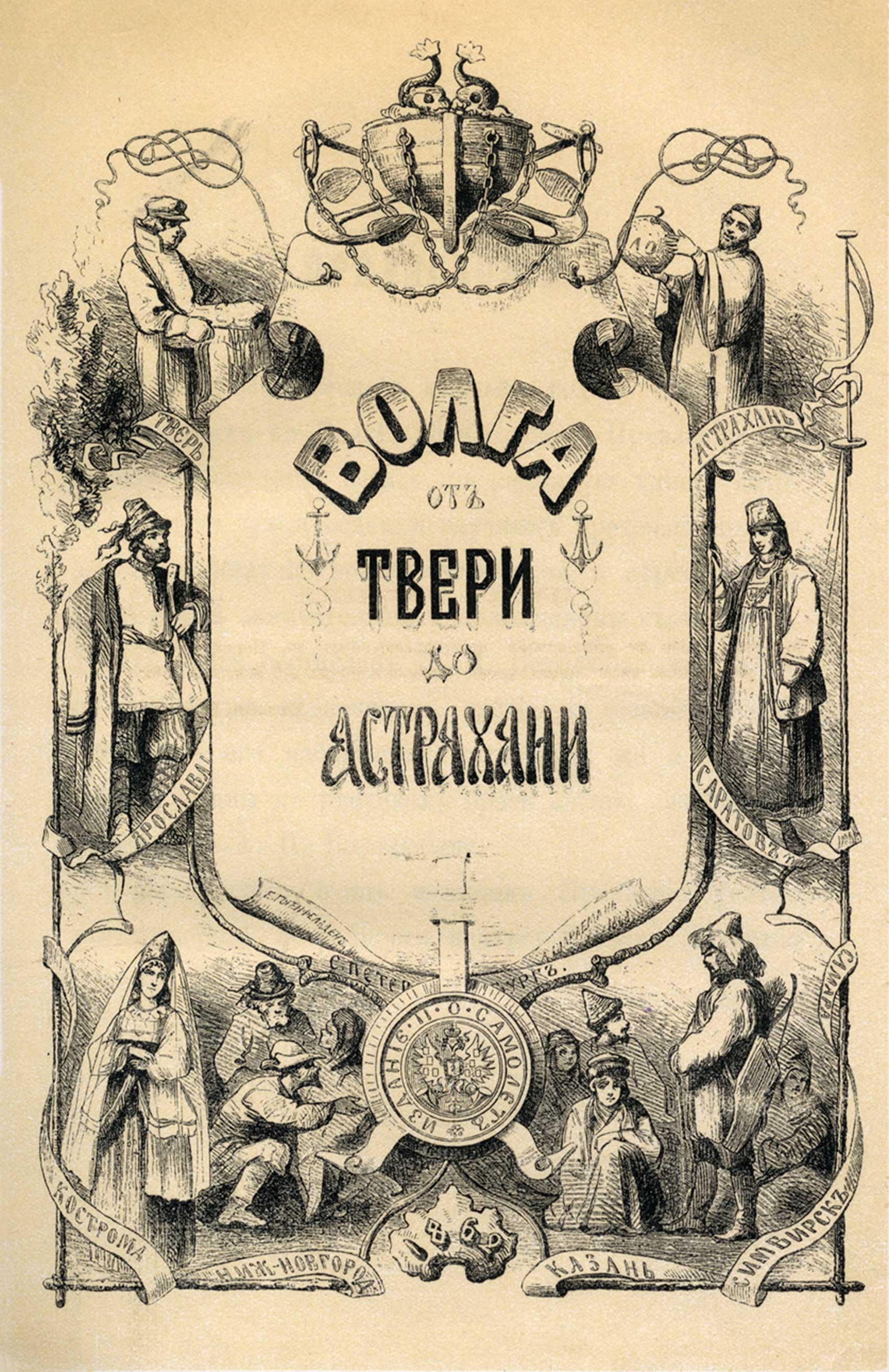

Despite being the last big player to emerge on the scene, Samolet made a name for itself early on by publishing a first-of-its-kind guidebook to Russian river travel. The Volga, from Tver to Astrakhan hit the shelves in 1862.

The volume was graced with dozens of lithograph illustrations and sketches by one of the finest artists of the day, Aleksey Petrovich Bogolyubov. Bogolyubov just happened to be sailing down the Volga for another purpose entirely, having been commissioned by the Naval Ministry to collaborate on a hydrographical atlas of the Caspian Sea. When they found out, Samolet asked Bogolyubov to document the picturesque towns and landscapes along their route.

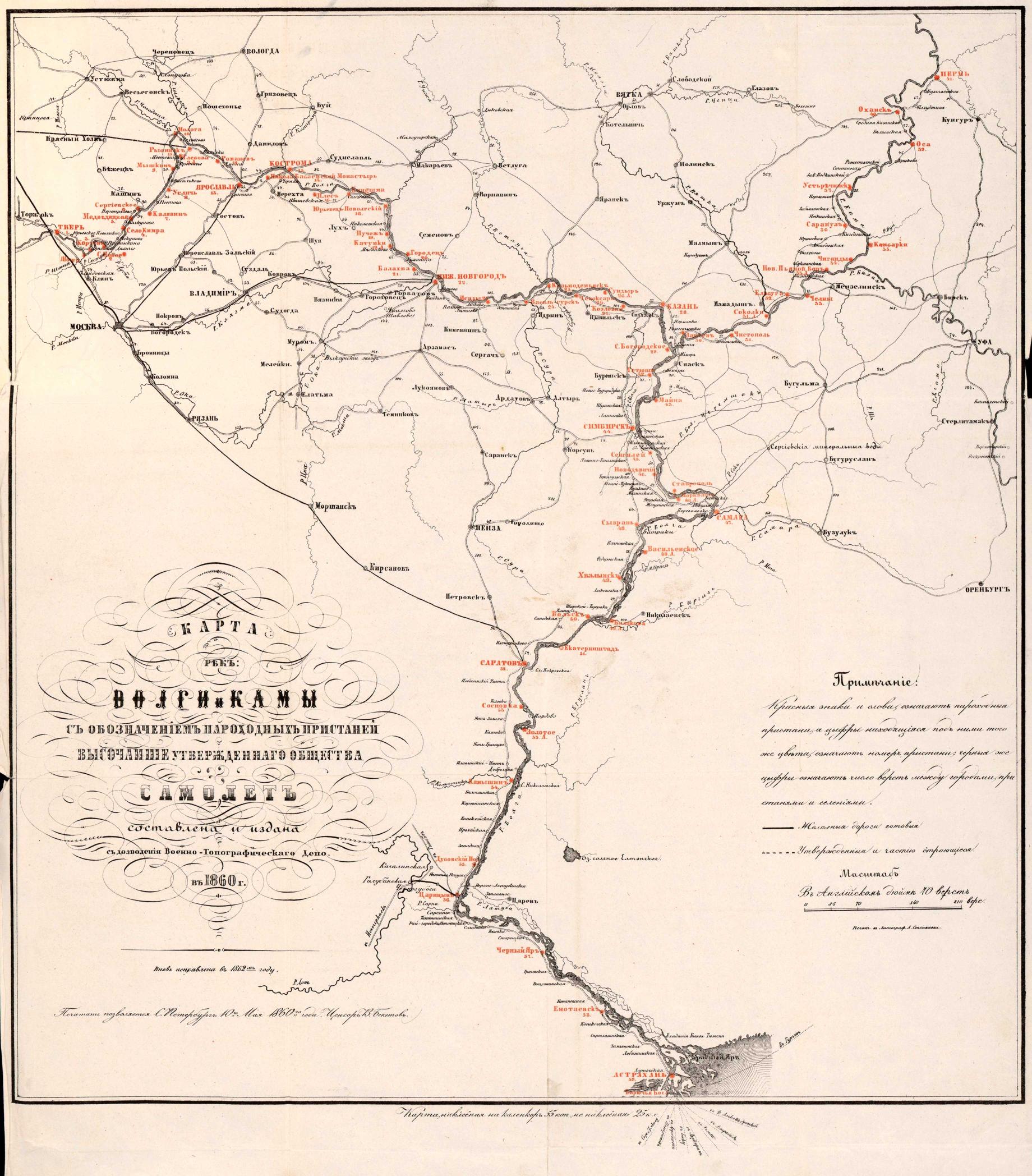

Samolet’s Volga guidebook also included a map.

And on the map, wedged in between Cheboksary and Kozlovka, is Sundyr’.

Knowing that the wheels of government did not always turn with lightning speed (especially while the empire was at war, which it was between 1853 and 1856), I thought at first that the cartographer might not have known about the creation of Mariinsky posad—the decree could not possibly have attracted much public attention.

However, this map was approved by the Military Topographical Depot in St. Petersburg—home to the best geographic intelligence and the best cartographers in the Russian Empire. Although all things are possible, this makes information failure a less likely possibility.

As I often remind my students, everything on a map is there for a reason: understanding the map depends on your ability to understand those reasons. And the reason for the inclusion of Sundyr’ on the Samolet map is right in the title.

It turns out this is not a map of the towns and villages along the Volga: it is a map of the Samolet Company’s wharves. The tsar replaced the name of a settlement in 1856, but not the name of the Samolet Company's wharf. After 1856, steamers could call at Mariinsky posad, but then again, they could call at the Sundyr’ wharf at Mariinsky posad. At Sundyr'.

In that sense, the beautiful Volga route map isn’t wrong.

But is it conceivable that the fine gentlemen at the Baedeker offices in Leipzig 1) got their hands on the Samolet map, and 2) chose to use it—over the course of multiple editions—as the authoritative source for the Volga itinerary instead of a range of other possible sources?

It is.

Can I prove it?

I can’t. Not at the moment, anyway.

However. Travel infrastructure was the foundation of the Handbook. Without reliable details about the cost, duration, and accessibility of rail lines, steam navigation, and carriage routes, the Handbook could not serve its purpose. A detailed map of wharves, including distances and connections to railways and roads, would have been worth its weight in gold and relatively easy to acquire. (In fact, the map was available for purchase affixed to buckram, a stiff cotton material commonly used for bookbinding and map backings, for 55 kopeks or as a paper sheet for 25 kopeks—not much gold involved at all.) The Volga and Mercury companies shared Samolet’s naming practices (not exclusively, but more often than not), which means there was consistency across the industry as well as across the decades.

Coincidence might have had a hand as well. Samolet remained a major player in passenger steam travel, but by the 1870s its fleet was in need of an upgrade. So the company made a splashy move, investing in new American-style steamers that launched in 1882—just as the Baedeker men were putting the finishing touches on their first guidebook to Russia.

References to the company are scattered throughout the Handbook—both in the itineraries and on the maps—and clearly outnumber mentions of rival companies.

One almost gets the impression that Baedeker played favorites.

Samolet demonstrated a talent for staying in the headlines, even overcoming a fatal onboard fire to become one of the most trusted lines on the Volga. And in 1914 there it was, fashionable and relevant. Its routes expanded and its fleet much improved, but its wharves as constant as the stars.

Samolet called at Sundyr'. Therefore, in the world of leisure travel, Mariinsky posad did not exist.

It Comes to This

GeoNames and Google would beg to differ. They know just where to find Mariinsky posad. And to give them due credit, they are adept at locating the various settlements that use the toponym Sundyr’.

What they cannot do is recognize that none of the versions of Sundyr’ they hold in their databases are the place I was looking for. What they cannot understand is that Mariinsky posad used to be called Sundyr’.

Why?

Because no one told them. That’s right. In simplest terms, we have put our finger on one of the places where the powerful feedback loop between human knowledge and mechanized (and digitized) processing systems breaks down. Not only that. We have stumbled upon one of the countless-but-subtle bits of evidence of the inconsistency of modern data: for while Google and GeoNames stumble on Sundyr', the Yandex Maps platform (the Russian equivalent of Google Maps), when asked to located Sundyr', drops its placemark right at Mariinsky posad.

This is not a criticism of modern gazetteers or mapping platforms. It is a call to action.

It comes to this. Those of us who study the past are custodians of unique, often hard-won, troves of data. By virtue of inhabiting the digital age, we have the capacity to visualize huge swaths of historical terrain. We have the capacity to mend (some of) the gaps between human and machine—between the practice of scholarship and the power of computation. In fact, we have the capacity to not just fill in those gaps for others but to add the dimension of space—and the analytical power it brings—to our own studies of political, social, and cultural change.

If it ever was, it no longer is enough for a lone historian to know that Sundyr’ is not where Google says it is, but somewhere else entirely. We can write the history of the Russian Empire without Sundyr’. But we cannot understand the past without understanding the systems and practices that create, mobilize, and assign meaning to geographic information.

Information is the currency of the modern world, and we students of the past are swimming in it. But information was always the currency of empires. I, for one, lay awake at night thinking about context and contingency, space and time, the point of diminishing returns, and the power of putting the past on the map. When I wake in the morning I tend to have the same thought: it is time for us to build something together. We can tell Google about it later. Maybe. For now, let’s start by assessing what we know. Let’s talk. Let’s share. Let’s map.

Let’s produce some functional beauty.