By the time a wave of Futurists, Rayonists, and other avant-garde artists fleeing the Russian civil war poured into the capital of briefly independent Georgia, the city was already bubbling with modernist ferment. The largest metropolis in the South Caucasus, Tiflis (renamed Tbilisi in 1936) had been one of the Russian empire’s most colorful and multinational cities — “fruitful soil” for artistic innovation with its “conglomeration of mutually contradictory ideas and views,” in the words of art historian Nana Shervashidze. It was there Ilya Zdanevich (1894-1975) grew up, with revolution in the air, eventually joining an artistic insurgency against imperial rule.

Later styling himself “Iliazd,” Zdanevich came from a family of liberal, artistic intelligentsia. His father, of Polish origin, graduated from the Sorbonne and translated Filippo Marinetti’s Futurist manifesto into Russian for his two sons. His mother, Valentina Gamkrelidze, studied with Pyotr Tchaikovsky. His older brother, Kirill, was an artist. Together, the Zdanevich brothers, along with poets Igor Terentyev and Alexei Kruchenykh, founded the avant-garde group “41 Degrees” in their native city in 1917; after a brief spell in Constantinople, Iliazd moved to Paris in 1921, never to set foot on Soviet soil.

Art historians recognize Iliazd’s impact on the European modernist movement and his unique contribution to the concept of the book as a work of art, but few people are aware of the breadth of his talents — inventor, poet, designer, typographer, novelist. This week, marking 130 years since Zdanevich’s birth, a dozen international scholars will gather to share their research on this multi-faceted creator at a symposium hosted by the Davis Center’s Program on Georgian Studies and Harvard’s Houghton Library, which holds an impressive collection of his work. Among Houghton’s books is Iliazd’s 1923 typographic tour-de-force Lidantiu Faram (“Le-Dantiu as a Beacon”), one of the most well-known and beautifully printed books of the Russian avant-garde. Combining hundreds of different typefaces, the book is an incredible feat in the medium of letterpress printing.

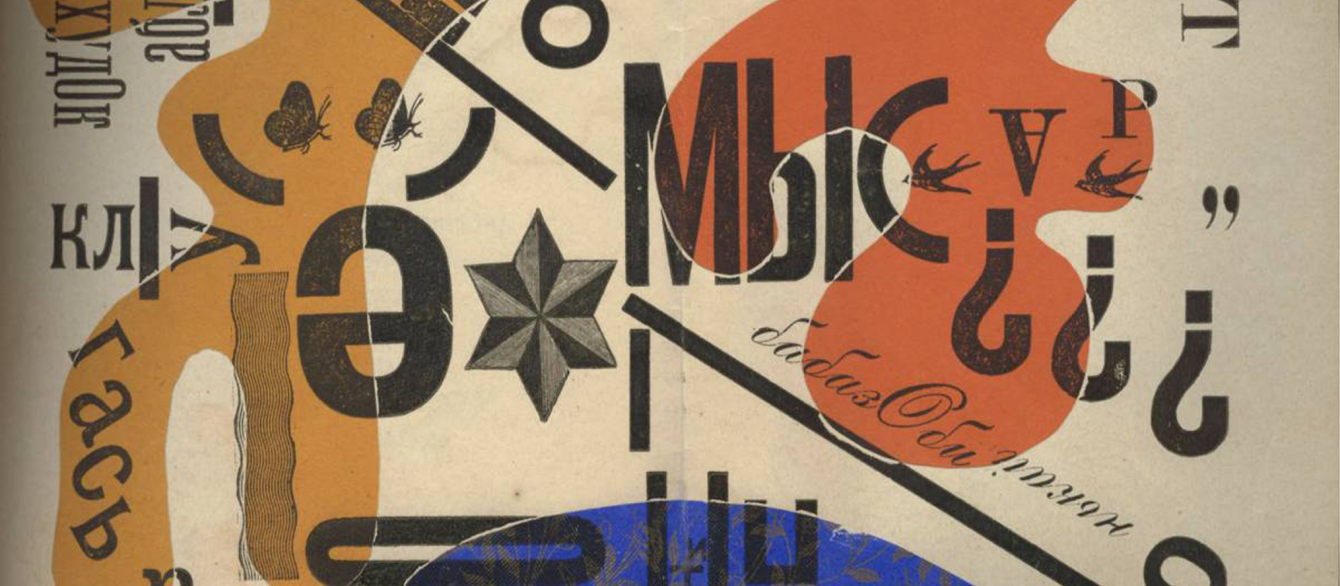

![Lidantiu Faram [“Le-Dantiu as a Beacon], Paris 1923](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-10/lidantiu%20faram.jpg?itok=V2GIapgX)

Pages from Lidantiu Faram, written in zaum, the experimental "trans-rational" language embraced by some Russian-speaking Futurists.

Iliazd’s books, known as livres d’artistes, were produced by the artist from his youthful days in Tiflis through the rest of his life. For his most famous 21-book series, published in Paris between 1940 and 1975, Iliazd solicited unique creations from Europe’s greatest artists, many of them his friends — Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Marc Chagall, Alberto Giacometti, Max Ernst, and others. For Iliazd, a book was not a mass-produced artifact but a stand-alone work of art, handmade, each one different, comprising etchings and images surrounded by typographical experimentation and unusual print designs. Parchment was used for the covers and different types of paper for the pages. Each book focused on a theme and told a story.

The livre d’artistes was not invented by Iliazd, but he dominated the genre for decades. During the short period of Georgian independence (1918-1921), he was recognized as one of the most groundbreaking artists in town, manipulating typography and typesetting to create books that mixed experimental designs and unfamiliar poetic forms. One of the earliest was To Sophia Georgievna Melnikova: The Fantastic Tavern, published in 1919. Dedicated to Melnikova, a famous actress and a supporter of young artists’ bohemian performances in the street café known Fantasticheskii kabachek (The Fantastic Tavern), it contained poems, paintings, stories, notes, and lectures by avant-garde poets, painters, and even academics in Georgian, Armenian, and Russian.

Iliazd never painted in his life, but his book creations and other work — including textile prints made over his many years as one of Coco Chanel’s chief designers — have been the subject of several exhibitions over the last few decades. Among his other creative projects, Iliazd promoted and performed zaum — an experimental poetic language developed by Kruchenykh based on phonetics and rhythm rather than grammar or syntax. Iliazd wrote several zaum dramas (he called them dra), such as Yanko krul albanskai (“Yanko, the King of Albania”).

Though Iliazd never returned to Tiflis, his impact on Georgian modern art remains. This week’s two-day symposium, we hope, will illuminate his work further and put him in the context of his times, both in Tiflis until 1921 and in Paris until his death in 1975.