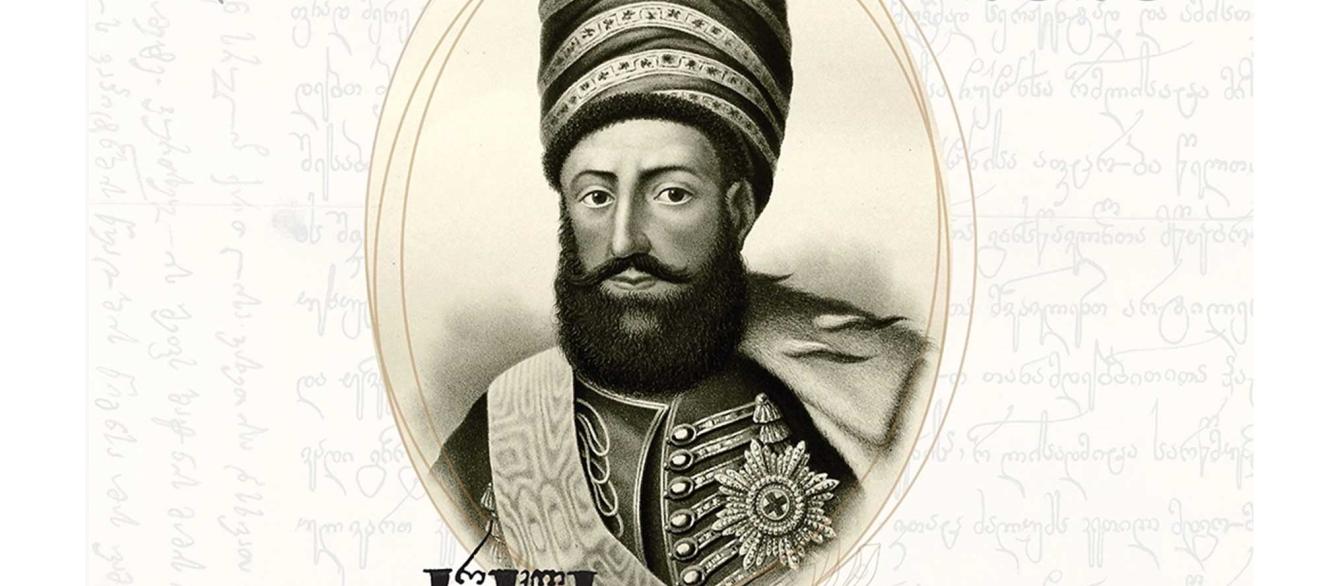

Was an 18th-century king of Georgia, Erekle II, a “traitor”? That was the recent claim of Levan Berdzenishvili, one of Georgia’s more liberal commentators. Berdzenishvili was revisiting a pivotal moment in Georgian history, the 1783 Treaty of Georgievsk. Erekle signed the treaty with Russian Empress Catherine the Great, believing it would defend Georgians against Persian and Ottoman threats from the south.

The treaty transformed the independent kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti into a Russian protectorate and was the beginning of two centuries of Georgian subordination to the Russian, and subsequently Russo-Soviet, empires. The treaty was a reminder of the limited leverage small states have against ambitious imperial neighbors, a lesson with obvious salience in Georgia today.

Berdzenishvili, a former member of the liberal opposition Republican Party, made his argument on an obscure internet channel. But it soon became a national scandal, setting off a chain reaction of mutual recrimination among Georgian intellectuals. It shone a harsh spotlight on two prominent features of Georgian politics today: the powerful impact of a living past on the present, and the use of language to demonize the opposition.

Following Berdzenishvili’s comments, the chairman of the ruling Georgian Dream party, Irakli Kobakhidze, claimed they amounted to an attack on Georgian national identity. He called Berdzenishvili and the country’s largest opposition party, the United National Movement (UNM), “Bolsheviks of the new age.” Berdzenishvili’s remarks, Kobakhidze continued, were a “depraved speech of a man imbued with hatred, without a god and a homeland.”

Words like “traitor” and “Bolsheviks” are now integral parts of Georgian political speech. After thirty years of independence, Georgian contemporary discourse remains stuck in the revolutionary era of turncoats, conspirators, and apostates.

Language is at the heart of democracy. It can preserve it, or it can destroy it. Today, it plays a destructive role in Georgia, exemplified by the debate over Erekle II. George Orwell warned us long ago that the deterioration of language is closely connected to the decline of democracy. He suggested a symbiotic relationship exists between the two: politics affects what language we use, and language affects the politics we experience.

The language employed by Georgia’s politicians today, in parliament, television, and social media, reflects the erosion of the country’s democratic institutions. Language no longer serves as a form of communication between parliamentarians and constituents to describe policies, provide information, or promote dialogue.

Georgia’s polarized elites bear the blame for this. In their desire to grandstand and mobilize support, they use language designed to divide. Language has become a polarizing instrument used to distract citizens from the real problems facing Georgia today. But ordinary Georgians are not polarized over what really matters to them. Public opinion surveys consistently show that ordinary Georgians see healthcare, unemployment, and prices as their major priorities.

Yet the language of Georgia’s political leaders is focused on ridicule, threat, coercion, and violence, and has little connection to their constituents’ reality. Deliberation, persuasion, or a conciliatory linguistic tone or style have rarely governed Georgian political elites, but today, linguistic extremism is the norm. Language is dictating politics rather than the other way round.

Language is at the heart of democracy. It can preserve it, or it can destroy it. Today, it plays a destructive role in Georgia.

This has led to a bifurcated political system in which parties have no clear social or political constituencies that might pressure them into concrete policies to address concrete problems. This disconnection from reality gives populist leaders wide linguistic freedom – more often than not, it produces a vocabulary which will take no prisoners and only imagine enemies. It has led to violent debates over Erekle II, when the real problem is unemployment and massive social and economic inequalities.

Consciously or not, Georgia’s leaders have absorbed Soviet techniques of linguistic manipulation. Soviet political language created a discourse of incivility – poisonous insults, political labelling, ad hominem attacks and branding of the opposition as “traitors,” “enemies,” or worse. It eroded the ability to use language for dialogue or mediation.

Georgian political discourse today is not so toxic as it was in Soviet times, but the country’s political elites use it to promote an ideologization of daily life. Their language is fixated on the enemy within (homosexuality, religious minorities), or on opponents linked to the enemy without (Russian imperialism, Bolshevism, or the EU and the “West”).

Georgia is not alone. Donald Trump, Victor Orban and Vladimir Putin can outdo Georgia’s leaders when it comes to linguistic abuse of opponents and minorities. The vocabulary of war has infiltrated the dialogue of all modern societies – another of Orwell’s observations – but in Georgia over the last decade, it has taken on particular intensity.

It comes from an authoritarian impulse which uses language to control citizens. The government’s rhetoric depicts a war against Georgian traditional values. In defending Georgia against homosexuality, for example, radical rhetoric mobilizes a coalition of conservative church supporters and pro-Russian commentators against liberal civil society representatives and the opposition press. For the political opposition, such as the UNM, a parallel rhetoric depicts a society of pro-Russian conspirators and “agents of the Kremlin.”

Venomous insults made in public – in parliament or in TV studios – are rarely forgiven and discourage political cooperation. Democracy depends on basic levels of collaboration and consensus, and the use of extreme language destroys it.

It is easy to dismiss language like that of Berdzenishvili and Kobakhidze as theatrical, but it has serious consequences for Georgian politics at home and abroad. At home, this unbridled rhetoric encourages irreconcilability and violence. (Levan Berdzenishvili’s bother, Davit, was physically assaulted by unknown assailants in Tbilisi in apparent retaliation for Levan’s comments on Erekle II.) Venomous insults made in public – in parliament or in TV studios – are rarely forgiven and discourage political cooperation. Democracy depends on basic levels of collaboration and consensus, and the use of extreme language destroys it.

The consequences for Georgia abroad are equally bad. Georgians, already suffering from a patronizing reputation for hotheadedness, do themselves no favors with this linguistic extremism. Georgia now faces a period of self-reflection as the European Union, in considering the country’s membership application, said last week that it must first reform. European lawmakers, in a recently adopted resolution, identified a culture of toxic rhetoric and mutual blame in Georgia which only harms the country’s EU aspirations.

If Georgia’s leaders want to improve their country’s image in Europe (and everywhere else); if they want to establish some normality in current political life; if they want to connect with their constituents and strengthen the legitimacy of the Georgian political class, then the place to start is language.

This piece originally appeared in Eurasianet on June 20, 2022.