Forty years ago, in the late summer of 1982, the Soviet Union was under the rule of Leonid Brezhnev, who had been in power since October 1964. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) exercised stifling control of the country and routinely violated basic human rights and freedoms. The USSR was largely closed off from the rest of the world, and the CPSU prevented Soviet citizens from traveling abroad. The Soviet press was rigidly controlled, and most foreign publications were not allowed into the country. Brezhnev and other members of the CPSU’s ruling Politburo were supported by millions of troops in the Soviet armed forces and the vast apparatus of the State Security Committee (KGB). The dissident movement had been crushed during Brezhnev’s long reign, and ethnic tensions were largely dormant. Slower economic growth rates in the 1980s and lags in technological innovation were a problem for the CPSU but not a fatal one. The prospect that the USSR would disintegrate in less than a decade seemed entirely fanciful.

Over the next two-and-a-half years, the Soviet Union underwent several changes of leadership, culminating in the ascendance of Mikhail Gorbachev as CPSU General Secretary in March 1985. Gorbachev, who died on 30 August 2022 at age 91, ended up changing everything. He remained in power in the Kremlin for less than seven years, but during that time he transformed the USSR and Soviet foreign policy in truly remarkable ways. He had come to office seeking to strengthen the Soviet Union and to consolidate the Warsaw Pact military alliance under Soviet leadership. He ultimately failed to achieve either of these basic goals and instead presided over the dismantling of the Warsaw Pact and the dissolution of the USSR. But even though he failed to accomplish his main goals, his failures were accompanied by magnificent achievements. The Cold War and all the dangers it posed came to an end in the late 1980s and early 1990s in large part through Gorbachev’s efforts. Although other political leaders such as Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush also played important roles in ending the Cold War, Gorbachev deserves the greatest share of the credit. Few leaders in modern history have had as great an impact on the world and on their own countries as Gorbachev did during his brief tenure.

The stream of disclosures about the Soviet past and about the deficiencies of Soviet society did not spark mass unrest, but it did have the cumulative impact of delegitimizing the Soviet regime in the eyes of many Russians as well as non-Russians.

In the first eighteen months after coming to power, Gorbachev pursued relatively orthodox policies of uskorenie (acceleration), with only modest results. Even when he shifted to a more ambitious agenda of perestroika (restructuring) in the aftermath of the 27th Soviet Party Congress in February-March 1986 it was not yet clear whether he would take the Soviet Union in a genuinely new direction. This began to change in the latter half of 1986 and 1987, especially with the release of Soviet political prisoners and dissidents such as Andrei Sakharov and with the inception of glasnost, a policy of official openness that soon expanded to give much greater leeway to newspapers and journals to cover previously taboo subjects.

The greater openness of Soviet press coverage was reinforced by Gorbachev’s decision to open Soviet society to the outside world. By early 1988, international telecommunications links were markedly increased, and ordinary Soviet citizens were allowed to travel abroad. Foreign corporations were encouraged to establish joint ventures with Soviet partners and to undertake investments that were previously off-limits. Gorbachev began drastically expanding the number of exit visas given to Soviet Jews to emigrate to Israel, symbolized by the release in 1986 of the renowned dissident Anatoly Shcharansky (Natan Sharansky), who had spent nearly a decade in a harsh prison camp for his defiance of Soviet tyranny.

Soviet economic reforms were a much more formidable challenge. Gorbachev could not bring himself to adopt radical free-market reforms as Deng Xiaoping had implemented in China at the end of the 1970s. Gorbachev sought instead to reform, rather than jettison, the Soviet economic model. But he gradually came to believe that far-reaching political liberalization would be a prerequisite for economic advancement. From mid-1988 on, he combined perestroika and glasnost with demokratizatsiya, including the first free elections the Soviet Union had ever held. As the CPSU gradually relinquished its grip over political and social life, unrest emerged in many parts of the Soviet Union, particularly the Baltic republics, the Caucasus, and Moldova, where separatist movements and political instability gradually spread.

The freer flow of information under glasnost contributed to the decline of central control. Soviet citizens could finally read about the full magnitude of Stalin-era crimes, the wide range of social problems afflicting the Soviet Union — alcoholism, juvenile delinquency, declining health indices, homelessness, spiritual malaise, crime, poverty, and the disaffection of young people — and the destruction caused by natural disasters, accidents, and environmental pollution. The stream of disclosures about the Soviet past and about the deficiencies of Soviet society did not spark mass unrest, but it did have the cumulative impact of delegitimizing the Soviet regime in the eyes of many Russians as well as non-Russians.

Glasnost also had a profound impact on Soviet elites, who were suddenly free to talk about the regime’s past iniquities and the Soviet Union’s “failure to measure up to the civilized world” (as Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze put it). The exposure of Stalinist crimes, and the outpouring of criticism about the continued shortcomings of Soviet life, eroded the morale of elites who had previously been loyal to the Communist system. Even though Gorbachev believed that these trends would ultimately benefit his reforms and strengthen the Soviet Union, a hardline backlash began to emerge in the CPSU and KGB.

The vastly greater leeway for political protest and mobilization in the late 1980s came at the same time that economic conditions were sharply deteriorating. Ironically, in the two years prior to Gorbachev’s emergence as leader of the CPSU, the Soviet economy had actually been improving. Although economic growth rates had been lagging since the early 1970s, the economy was not in crisis in 1985 and could probably have continued functioning indefinitely. Gorbachev's own economic policies, which led to macroeconomic imbalances, soaring inflation, rampant shortages, the stripping of assets of large firms, and a rapid buildup of foreign debt, destabilized the economy and produced a genuine crisis by 1990 and 1991. The hardships that resulted from Gorbachev’s failure to pursue an effective economic program generated widespread social discontent.

The confluence of these trends by the end of the 1980s produced a highly volatile mix that was made even more combustible by the increasing polarization of key elites. On one end were hardline officials in the CPSU and KGB who wanted to roll back the reforms and to reassert centralized control. On the other end were radical reformers (including Sakharov and other former dissidents) who were disappointed that Gorbachev was not moving faster and who were intent on creating new political parties to supplant the CPSU. The more moderate reformers led by Gorbachev were increasingly isolated in a tenuous middle position.

Gorbachev's refusal to lend his imprimatur to the putsch during the crucial first few days was decisive in depriving the GKChP of any legitimacy it might have attained and in ensuring the coup’s failure.

Many of the radical reformers coalesced around Boris Yeltsin, who had staged a remarkable political comeback in 1989 after being demoted and humiliated by Gorbachev in October 1987. Although Yeltsin remained a CPSU member until July 1990, he increasingly presented himself as an anti-establishment and populist figure who would confront the party hierarchy. Voters in Moscow overwhelmingly elected Yeltsin to the new Soviet legislature, known as the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies, in March 1989, despite strong opposition from senior CPSU officials. Yeltsin used this new platform to call repeatedly on Gorbachev and the CPSU to move much faster with political and economic reforms.

Yeltsin’s position was strengthened still further in June 1990 when he gained the chairmanship of the newly created Russian parliament and, a few weeks later, when he demonstratively walked out of the CPSU’s 28th Congress and renounced his party membership. Over the next year, he kept up his pressure on Gorbachev and continued to demand much bolder reforms. When Yeltsin was elected by a wide margin to the new Russian presidency in July 1991, he had an even stronger vantage point from which to challenge Gorbachev and the Soviet regime.

Despite Yeltsin’s increasing assertiveness, Gorbachev tried to hold the Soviet Union together by forging a new relationship between the center and the union republics. Prolonged negotiations toward this end in 1990-1991 were plagued by difficulties, but the mere possibility of a lasting accord that would bring about far-reaching decentralization inspired hardliners in the KGB, the army, the military-industrial complex, and the CPSU to launch a coup d'état on 19 August 1991, the day before the scheduled signing of a Union Treaty that would have reconfigured center-republic ties. The coup did not come entirely out of the blue. It was preceded by the abrupt resignation of Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze in December 1990 (as he warned of an impending hardline backlash), a violent crackdown in Lithuania and Latvia in January 1991, an attempt to stage a “constitutional coup” in June 1991, and the publication of an ultra-hardline “Word to the People” (Slovo k narodu) manifesto in July.

Several months prior to the coup, Gorbachev had authorized planning for a general crackdown, and he therefore knew at least in broad terms that a coup was in the offing. But the evidence indicates that Gorbachev did not condone the specific attempt that occurred on 19 August and that his refusal to back the conspirators proved decisive in the coup's failure on 21 August. By all indications, the leaders of the putsch — who set up a State Committee on the State of Emergency (GKChP) to oversee matters — were hoping that Gorbachev would reluctantly join them if they forced his hand. Although it is impossible to know what Gorbachev might have done if the coup had lasted longer and the conspirators had been more resolute in cracking down on unrest, his refusal to lend his imprimatur to the putsch during the crucial first few days was decisive in depriving the GKChP of any legitimacy it might have attained and in ensuring the coup’s failure.

President Reagan and General Secretary Gorbachev signing the INF Treaty in the East Room of the White House, December 8, 1987.

The coup failed not because the plotters lacked enough force to carry it out — they in fact had immense numbers of well-armed troops at their disposal — but because they were averse to taking responsibility for large-scale bloodshed unless they received explicit authorization from the country’s highest command authority (namely, Gorbachev). This dynamic underscores the enormous importance of the top leader’s role in the Soviet political system. Even though the heads of the key institutions of power in the USSR — the army, the KGB, the Internal Affairs Ministry, the military-industrial complex, and the CPSU apparatus — were all complicit in the coup, their backing was insufficient without direct authorization from the very top. If the CPSU General Secretary was unwilling to resort to mass repression, other high-ranking officials did not want to accept responsibility for causing widespread loss of life.

The failure of the putsch prefigured the collapse of the USSR itself four months later. The rebuff of the coup gave unstoppable momentum to several of the union republics — the Baltic states, Georgia, Moldova, and others — in their drives for independence. Of particular importance was Ukraine. In the absence of the failed coup attempt, the independence movement in Ukraine probably would not have gained the momentum that it did by December 1991. As recently as March 1991, when a countrywide referendum was held on the future of the Soviet Union, nearly three-quarters of voters in Ukraine had been in favor of preserving the union. But the aborted coup profoundly altered public sentiment in Ukraine. The Ukrainian parliament reflected the new mood by adopting an independence declaration on 24 August 1991. When a republic-wide referendum was held in Ukraine on 1 December, more than 90 percent voted in favor of full independence, a result that led a week later to the signing of the Belovezhskaya Pushcha accords that codified the end of the Soviet Union.

Even as fissiparous trends in the USSR intensified during the final four months, Gorbachev was unable to take effective remedial action. Yeltsin's highly visible role in the resistance to the putsch — symbolized most vividly by his standing on top of a tank — enabled him to gain clear ascendance over Gorbachev once the coup was rebuffed. The Russian leader promptly recognized the independence of the Baltic states, Georgia, and Moldova. Although Yeltsin initially wanted to preserve the rest of the union as a Russian-led federation, he was intent on reducing the Soviet regime to a mere figurehead status, if that. His efforts in this regard in the last few months of 1991 accelerated trends that ultimately forced him to accept the outright disintegration of the union.

Coercive options, which had played such a prominent role in the USSR from the time it was founded, were no longer a practical means of holding the USSR together after August 1991. The rebuff of the coup had undermined the CPSU and severely weakened the KGB, the army, and the Soviet government. None of these institutions was in any position afterward to rely on violence as a last-ditch means of trying to keep the Soviet Union together. Yeltsin promptly suspended and then banned the CPSU, bringing a de facto end to Communist rule. The KGB and the army were temporarily immobilized and were incapable of resisting the breakup of the Soviet state. The failure of the coup was decisive in eliminating any further willingness on the part of top elites to resort to large-scale repression. Although Gorbachev raised the possibility of a military crackdown in a private conversation with the Soviet defense minister as late as mid-November 1991, he undoubtedly realized that it was much too late for such a step even as he proposed it.

With Gorbachev relegated to a subordinate position in the aftermath of the coup, Yeltsin worked sedulously in the fall of 1991 to ensure that the Soviet regime would play no more than a ceremonial role in a new political structure. No longer did Yeltsin seek to cooperate with Gorbachev in any sustained way. Although both men hoped to preserve a union after 21 August, their conceptions of the entity that should emerge were incompatible. The resounding shift of public opinion in Ukraine in support of outright independence, as reflected in the voting results on 1 December, is what ultimately forced Yeltsin to change his goals and precipitate the demise of the Soviet Union through the Belovezhskaya Pushcha agreements, which he signed on 7-8 December with Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk and Belarusian leader Stanislau Shushkevich. But even if the situation in Ukraine had not changed so dramatically, it is questionable whether a viable union structure could have been devised that would have satisfied both Yeltsin and Gorbachev as well as other leaders of the republics that were still part of the USSR.

Russian President Boris Yeltsin, right, confronts Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, left, during a special session of the Russian Federation Parliament in Moscow on Friday, August 23, 1991.

When ordinary Russians suddenly learned on 8 December 1991 that the Soviet Union was going to be dissolved by the end of the year, they did not take to the streets in protest. On the contrary, Russian society reacted to the Belovezhskaya Pushcha accords with evident relief and even, in some cases, with indifference. Gorbachev had desperately wanted to preserve the Soviet Union, but his effort to do so was greatly complicated by the public mood in Russia during the final few months of 1991. In the aftermath of the Belovezhskaya Pushcha meeting and another meeting in Kazakhstan two weeks later that officially set up the Commonwealth of Independent States, Gorbachev faced up to reality. He resigned all his offices on 25 December 1991, and the next day the Supreme Soviet of the USSR formally approved the dissolution of the Soviet Union, bringing an end to the state the Bolsheviks had created after coming to power in Petrograd in November 1917.

The dissolution of the USSR seemed inconceivable before Gorbachev came to power, but one of the consequences of his policies — obviously an unintended consequence — was the growing public perception in Russia that the demise of the Soviet state was bound to occur and was therefore not worth resisting. Although Russians were not inclined to end Soviet rule through the use of force, the important thing by the end of 1991 was that all major social groups in Russia no longer had a stake in the future existence of the USSR. Russia’s important role in the breakup of the Soviet Union is worth recalling today. In 2005, Vladimir Putin claimed that the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991 had been “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the [20th] century,” but this assertion glosses over Russia’s own key role in precipitating the outcome Putin now laments.

The dissolution of the USSR seemed inconceivable before Gorbachev came to power, but one of the consequences of his policies was the growing public perception in Russia that the demise of the Soviet state was bound to occur and was therefore not worth resisting.

When the Soviet Union broke apart, Gorbachev was only 60 years old, the same age as Yeltsin. The two men never reconciled. One of the tragic consequences of the lasting animosity between them is that they did not cooperate in late 1991 and early 1992 in taking steps that would have given a fillip to genuine democratization in the new Russian state. The most fundamental steps that were needed in the wake of the abortive coup were the permanent dismantling of the KGB, the banning of all KGB personnel from public office at any level, and the demolition of the entire Lubyanka headquarters of the KGB. The KGB’s deep involvement in the coup created a window of opportunity for Gorbachev and Yeltsin to get rid of the agency after the coup fell apart. The prospects of success in disbanding the security apparatus would have been especially great if the two leaders had acted together on the matter in the final months of 1991. If just one or the other had taken such a step, opponents of the move would have had an easier time trying to derail it. But if Gorbachev and Yeltsin had worked together, they undoubtedly could have gotten rid of the KGB and thereby eliminated the main obstacle to democratization in Russia. One of Yeltsin’s closest advisers, Gennadii Burbulis, raised this very matter with Yeltsin and suggested that they enlist Gorbachev’s support for it, but Yeltsin brushed aside Burbulis’s proposal and decided to keep the KGB and simply rename it.

In the aftermath of the failed coup, senior KGB officers themselves had worried that Gorbachev or Yeltsin (or both) would seek to dismantle the state security organs, and they were relieved when nothing of the sort ultimately happened. The renamed security apparatus in Russia (now the Federal Security Service) inherited the personnel and resources of the KGB and quickly regained a dominant position in Russia, enabling it to thwart lasting progress toward democratic governance.

Despite the grudge Gorbachev felt toward Yeltsin, the former Soviet leader did not condemn some of the most unsavory steps Yeltsin took after 1991, including coercive actions the Russian government pursued vis-à-vis neighboring countries, notably Moldova, Georgia, Tajikistan, and Ukraine. Despite all the differences between Gorbachev and Yeltsin, they were alike in believing that Russia was entitled to a privileged sphere of influence in former Soviet republics.

After Yeltsin stepped down at the end of 1999, Gorbachev initially welcomed the new Russian president, Vladimir Putin, and sought a cordial relationship with him. Over time, Gorbachev became unnerved by Putin’s reversion to autocratic rule and by the return of stifling repression, and he openly criticized some of the steps Putin took. But Gorbachev refrained from the blunter criticism one might have expected. During the years Gorbachev was in power in the USSR, he mostly avoided the use of large-scale violence both domestically and abroad. He later expressed pride that he had deemphasized the role of violence in the Soviet Union and had steered Soviet foreign policy away from expansionism and aggression. Even so, he supported Putin’s ruthless war in Chechnya from 1999 to 2009, and he also condoned the war Putin waged against Georgia in August 2008.

Most disturbing of all, from today’s perspective, was Gorbachev’s endorsement of Putin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and his support of the domineering position Putin adopted toward Ukraine thereafter, not least by fomenting and fueling a war in eastern Ukraine. Ukrainian officials who had been hoping that Gorbachev would oppose or at least distance himself from Putin’s heavy-handed belligerence toward Ukraine were left disappointed.

Gorbachev had been gravely ill in the months before his death, and he did not make any public comment about the war Russia has been waging against Ukraine since 24 February 2022. Aleksei Venediktov, a well-known Russian journalist, reported in July 2022 that he had spoken with Gorbachev by phone and that the former Soviet leader was “upset” (rasstroen) about the war, but Gorbachev’s foundation did not confirm that claim. Gorbachev himself certainly would not have launched an unprovoked war, and he undoubtedly regretted that Putin has made Russia an international pariah. He also likely would have been appalled by the atrocities committed by Russian troops and the cruelty inflicted on Ukrainian civilians. But whether he would have publicly condemned Putin’s military campaign is more questionable, despite the phone call with Venediktov.

His record in office was one of monumental achievement and epic failure. Assessments that focus on only one or the other are misleading.

The economic hardships that many in the USSR experienced during Gorbachev’s final years in power, and the economic upheavals that occurred in every former Soviet republic after 1991, resulted in extremely low favorability ratings for Gorbachev all over the former Soviet Union. Nowhere in the former USSR have opinion polls over the past 31 years turned up favorable attitudes toward Gorbachev. In Russia, for example, periodic surveys conducted by the Levada Center and other organizations have consistently shown that only a tiny minority of Russians view Gorbachev positively. Given the way the Russian government under Putin has tendentiously shaped the narrative of Soviet history for Russian schoolchildren — claiming, among other things, that Gorbachev was misguided in pursuing a rapprochement with the “bloodthirsty” West — Gorbachev’s image in Russia may remain negative for a long time to come. Putin was guarded in his reaction to Gorbachev’s death, and he declined to arrange a state funeral or day of mourning. Putin also indicated he would not attend the funeral in Novodevichy Cemetery on 3 September.

Nevertheless, at some point in the future, after generational change in Russia proceeds apace, a more balanced assessment of Gorbachev may well be feasible in his native country. His record in office was one of monumental achievement and epic failure. Assessments that focus on only one or the other are misleading. Gorbachev was instrumental in the end of the Cold War, and he brought hopes of freedom and democratization to Russia, giving the country a chance to become truly democratic. That opportunity was subsequently squandered under Yeltsin and was abandoned altogether under Putin, who reimposed autocratic repression at home and embraced military expansion abroad. Gorbachev cannot entirely escape blame for those setbacks, but the primary responsibility lies with his successors. None of what happened under Yeltsin and Putin, especially Russia’s brutal war against Ukraine, should be allowed to tarnish Gorbachev’s great achievements.

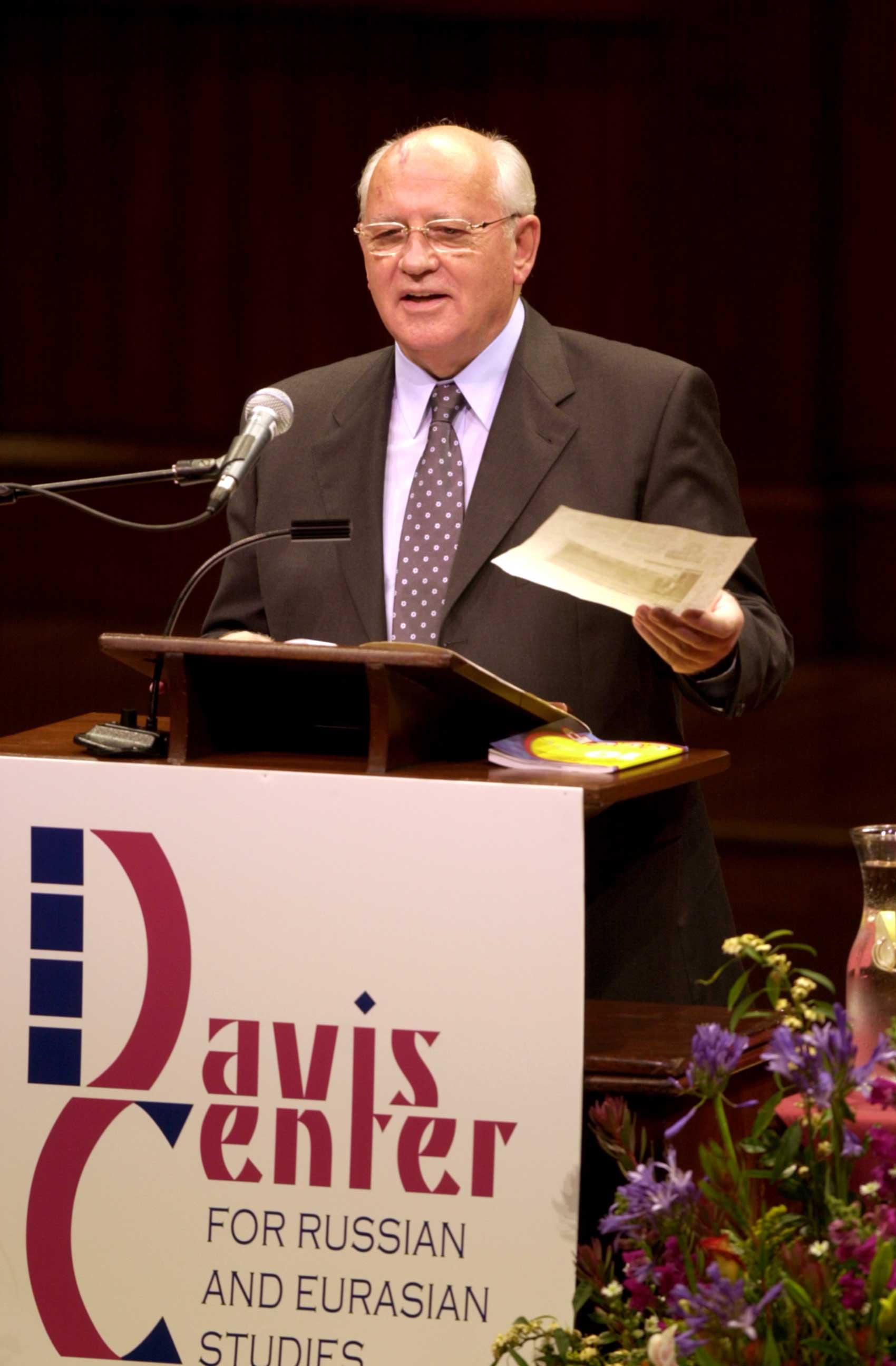

Mikhail Gorbachev delivers a speech, "Looking Back on Perestroika," at Harvard University on November 11, 2002.

In Western Europe and North America, Gorbachev has been viewed much more favorably than in the former Soviet Union. When Gorbachev came to Harvard University’s Davis Center in November 2002 and gave a lecture in Sanders Theatre, he was greeted by an overflow crowd of roughly 3,000 people (mostly students), who understood his immense historical significance. When he gave lectures in other Western countries, he drew crowds of similar size. The passage of time did not dim Gorbachev’s star in the West. After he died on 30 August, effusive tributes to him poured forth from Western government officials, journalists, political commentators, and academics. Some who paid homage to Gorbachev expressed reservations, and a few observers were harsh or sardonic, but by far the most common sentiment voiced in Western countries was lavish praise.

A year before Gorbachev died, he provided his own assessment of his record as leader of the Soviet Union. In a retrospective essay published in the journal Demokratizatsiya, he sought to explain why he had acted as he did in 1985-1991 and what he had been trying to achieve. He defended his record, but he also acknowledged numerous shortcomings and argued that “if given a chance to start anew, [he] would have done many things differently.” He said, for example, that he should have moved much more boldly on economic reform, should have acted much earlier to try to restructure the multiethnic Soviet federation, and should have realized much sooner that the CPSU was “incapable of transforming itself and unwilling to participate in reforms.” Even though one can argue that Gorbachev did not go far enough in highlighting the severity of problems he inadvertently created, he was commendably forthright in admitting that he wished he had “done many things differently.”

Gorbachev’s retrospective essay was accompanied by assessments from several leading Western scholars, who offered differing perspectives on his record and legacy. Scholars in the future will continue to debate Gorbachev’s performance and impact. Despite his egregious flaws and failings, he will almost certainly be remembered in the West mainly for his spectacular achievements, especially in helping to end the Cold War. In the former USSR, popular and scholarly assessments of him will likely remain dour for a long while to come, but even in Russia as the years pass the contempt for Gorbachev will likely diminish and the admiration for him will likely grow.