Editor’s note: After last month’s death of opposition politician and anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny in an Arctic prison, journalist David Remnick described him “not as … an ethereal intellectual, but as a grounded member of a hopeful generation: interested in freedom and prosperity. He even spoke of ‘happiness’ — hardly a common term in the … post-Soviet political lexicon.” REECA master’s student Polina Galouchko, from Moscow, represents that generation. Here she describes her responses to the grim news emanating from her native city over the past few years, including that of Navalny’s death. For a very different perspective on the politician, see this piece by REECA alumna Kimberly St. Julian-Varnon.

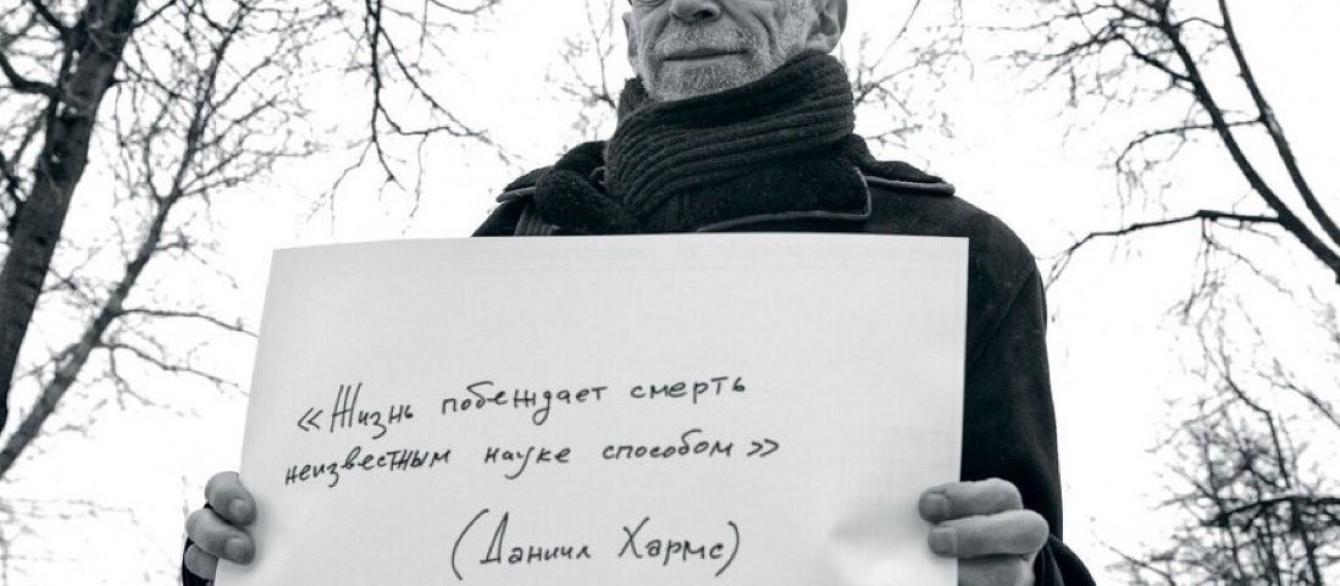

The first Davis Center event I ever attended was in February 2020 when poet Lev Rubinstein came to read his work. At the time, I was an undergraduate and did not know who he was. Before the event, I googled his name. One photo really stood out to me: Rubinstein holding a sheet of paper with a quote by poet Daniil Kharms (1905-1942): “Life defeats death in a way that’s unknown to science.” These words conveyed a sense of hope, in short supply even then; I saved the image on my phone.

The quote stuck with me and I kept going back to it over and over again. These were the first words that came to my mind when, in August 2020, Alexei Navalny miraculously survived a poisoning with the Novichok nerve agent. Life had defeated death indeed! This was the hope when he returned to Russia in January 2021 after recovering in a German clinic — knowing he would be jailed upon arrival. “It’s my country and I have no other,” he said and, as expected, was arrested at passport control. It was a snowy, cold January night, but thousands of people took to the streets. Navalny’s courage gave hope. “Russia will be free,” the crowd chanted, and the hope was palpable despite hundreds of arrests and police brutality.

A year later, in February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Horror and paralysis filled our days. I showed the picture of Rubinstein with his poster to a friend. “Yes,” she said, “Death has won indeed. A neighboring country is being destroyed.” I was confused: For me, the words had always carried the diametrically opposite message, invoking life’s victory over death, symbolizing hope even in the darkest of times. “Don’t you see?” she continued, “It says life is defeated by death in a way that’s unknown to science.” I realized then Kharms’s clever play with the accusative case in Russian grammar: Depending on the context, life could be the subject and death the object (i.e., life defeats death), or vice versa (i.e., death defeats life). Looking at photos of Bucha that spring, the latter interpretation suddenly seemed more plausible.

Lev Rubinstein was hit by a car and died in January 2024. Alexey Navalny was killed in a penal colony in Russia’s far north in February. Death — and war, and injustice, and violence, and fear, and repression — seemed to have triumphed. That’s what I was thinking when looking at the photos of Navalny’s 70-year-old mother searching for his body — the body of a son who had been tortured for years, yet unfailingly continued to give hope to his fellow countrymen by laughing right in the face of Leviathan and urging us not to give up, keep fighting. (“At least we’ll die honest,” he said.) For a week prison, morgue, and investigative officials refused to hand over the corpse for burial. Meanwhile, Putin promoted Russia’s deputy chief jailer to a higher rank. Death’s victory march was beating strong — and even stronger when you think about the hundreds of people imprisoned in Russia and in Belarus for treason, for “discrediting the armed forces.” It beats strongest of all when watching a film like “20 Days in Mariupol.”

I still haven’t read many of Rubinstein’s poems, but one of my favorites is “Life everywhere” (1989). Bits of life do start to show through, even amid death and darkness. My classmates from Moscow — we have lived our whole lives under Putin; we all watched Navalny’s anti-corruption investigations in high school; our families and loved ones were all hit by the regime in one way or another — sent me photos of flowers brought after Navalny’s death to memorials of the victims of Soviet repressions. The flowers were removed overnight, access to the memorials was blocked. People kept bringing flowers anyway. People wrote on walls, using the tender diminutive forms of Navalny’s and his wife’s names: “Lyosha + Yulia = love.” People commemorated him quietly in churches. Arrests and detentions followed, but there was life — life so clearly! — in all those actions.

My friend and I organized a vigil for Navalny on the steps of Harvard’s Memorial Church the day after his death. It seemed like the most natural thing to do: We felt total hopelessness — and that was what Alexei hated and fought against. We gathered on a cold, windy evening, like the one when Navalny came back to Moscow in 2021. We didn’t expect many people to show up. Around 30 came, bringing flowers and candles. We heard beautiful and courageous speeches. People cried. People hugged. After the vigil had ended formally, people stayed. Standing together, not necessarily talking, just being together — preserving this warm breath of life amid death and hopelessness. Looking around, I thought to myself that I don’t know what exactly Kharms meant, but I’m sure that both Lev Rubinstein and Alexei Navalny interpreted his quote optimistically: Life does defeat death in an irrational way. We need to be together, have courage to do what’s right, and never lose hope — no matter how irrational it seems. Hope that the war will end and that Russia will be free. And happy.

Navalny vigil in Harvard Square.