Editor’s note: It’s been more than a century since the Soviet project tore forth from imperial Russia, bloody and screaming. And it holds our attention still. Scholars keep writing new books on Soviet Communism, from its birth to its long-lasting impacts; writers and filmmakers draw on the Soviet past for their work; the legacy of Soviet militarism echoes through Russia’s war against Ukraine, sometimes in unexpected ways.

The Davis Center Library has recently digitized close to 200 Soviet propaganda posters in its collection. Together they form a visual history of official efforts to influence the USSR’s people throughout the country’s 70-year lifespan — from militant appeals against capitalism to the iconic “Motherland calls!” of World War II to little known gems supporting Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika efforts.

In our age of misinformation by meme, as history is again manipulated to justify violence and soft power still matters to Moscow, this poster collection sheds new light on the means and ends of propaganda — and the present digitization vastly expands access. The posters can now be browsed in Harvard Library’s digital image catalog. The images are accompanied by text in the original Russian and in English translation, making them keyword-searchable in both languages.

The following selection of 10 posters, ordered chronologically, with illuminating commentary by Davis Center alum and Harvard Slavic department Ph.D. student James Browning, gives a taste of the collection’s breadth.

The links in the poster titles lead to full-size images and additional information.

![Пролетарии всех стран, соединяйтесь! / Proletarii vsekh stran, soediniaites'! / [Workers of the world, unite!]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495222575.jpg?itok=m6sdU-qI)

Despite serving a cause that would soon spawn the world’s first officially atheist state, this poster glorifying the Red Army borrows heavily from Russian Orthodox eschatological iconography. A worker and a peasant astride a winged horse, now made indistinguishable by their military uniforms, occupy the place of Archangel Michael — also called the Archstrategist, who led a heavenly host against Satan in the Book of Revelation. They carry banners calling for victory over the White Russian generals Kolchak, Yudenich, and Denikin and for the establishment of a worldwide worker-peasant commune. Below them, the Kremlin, wreathed in the cleansing fire of revolution, is surrounded by a bristling multitude finally ready to shift to the offensive and drive the imperialist and interventionist armies (in the lower part of the image) literally out of the picture. The bottom caption reads: “Two years ago, the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army was born in the fire of revolution. In two years, the Red Army has grown to become a mighty force. It has surmounted thousands of obstacles. It has shattered dozens of imperialist governments. The hour is now approaching when our army will raise the red banner of the worldwide workers’ and peasants’ commune on the ruins of imperialism. Long live the Red Army!”

![Женщина! Учись грамоте! / Zhenshchina! Uchis' gramote! / [Woman! Learn to read and write!]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495222470.jpg?itok=uBzIYS2L)

This two-tone poster, mimicking the popular lubok or wood-block print, marks something of a transition from 19th-century private consumption of such artwork to the more public-facing art of 20th-century mass mobilization. It targets the same audience as the lubok: the less privileged and largely rural lower classes but does so obliquely. Instead of directing the child’s plaintive cries (“Oh, mommy, if only you could read and write, you’d be able to help me!”) toward an illiterate viewer, such a poster would have likely been displayed at a worker’s club with the intent to stigmatize illiteracy and generate public pressure supporting the early Soviet campaigns of likbez — short for likvidatsiia bezgramotnosti, or “the elimination of illiteracy.” While such campaigns aimed at eradicating illiteracy across the board, women — particularly rural women whose literacy rates lagged significantly behind those of men — were often specifically addressed. The illiterate peasant woman depicted in this domestic scene is still very much trapped in a prerevolutionary environment of housework and childcare. If women were to be emancipated as the Bolsheviks promised, literacy would have to be a key waypoint along that road. Beyond that, the modern Soviet state required a fully literate and mobilized populace. The likbez campaigns were extremely successful: The overall literacy rate, which hovered at about 24% for Imperial Russia in 1897, leapt to 81% for the Soviet Union in 1939, while rural areas saw an even more dramatic increase over the same period.

![Заменим! / Zamenim! / [We shall take their place!]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495222440.jpg?itok=6arkhsth)

Well over three quarters of a million women would serve in the Soviet Armed Forces during the Great Patriotic War — as WWII is still called throughout the former Soviet Union — but they were allowed to occupy combat roles only after the immense human losses of 1941 became apparent. Far more women played roles in agriculture and industry to support the front. Created in the first disastrous months of the war, this poster emphasized the need to mobilize all available resources for the defense of the Soviet Union and to fill the vacancies left by workers serving at the front.

![Наши силы - неисчислимы / Nashi sily -- neischeslimy / [Our forces are innumerable]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495222410.jpg?itok=fA7m7haO)

The selection of the Monument to Minin and Pozharsky as the touchstone of this poster is a logical choice that would have been unthinkable a decade earlier. In 1612, the merchant Kuzma Minin and Prince Dmitry Pozharsky raised a volunteer army that would ultimately defeat the Polish-Lithuanian occupiers and install the first Romanov tsar. The two became a symbol of the people — nobleman and commoner uniting to defend their native land. The statue faced an uncertain future after the October Revolution. It was denounced in the press for, among other things, its glorification of the boyar-merchant alliance that fed on peasant labor. However, Stalin’s endorsement of Russian patriotism during the Great Patriotic War allowed for symbols such as this statue to reenter the public sphere as positive and productive images that stressed continuities between the Soviet present and the tsarist past. Koretskii’s poster elects to view the statue as a symbol of the people’s unity and foregrounds a bearded peasant archetype as a modern Minin to lead the unified masses. Note the civilian dress indicating that, like the victorious army of 1612, this is a volunteer militia rather than a professional force.

5. “No!”

![Нет! / Net! / [No!]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495222164.jpg?itok=gBWelUqc)

The artist Al’bert Artemovich Aslian won a prize at the 1960 Venice biennale for this iconic 1958 anti-nuclear weapons poster, which would be reproduced in many forms over the years. While, at first glance, the poster suggests an unambiguous rejection of nuclear war, the inclusion of palm trees in the lower right-hand corner associates this fictional detonation with the U.S., whose extensive atmospheric tests were being carried out in the Pacific Proving Grounds, and points the viewer away from Soviet tests, largely held in the Kazakh steppe or Novaya Zemlya in the far north.

![Боннский "святоша" / Bonnskii "sviatosha" / [The Bonn "devotionalist"]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495222158.jpg?itok=8uvRH_cY)

While the Khrushchev era is largely remembered for its cultural “thaw” and a general relaxing of international tensions, there was always the possibility for the Cold War to turn hot. A year before the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, the status of Berlin was one issue with the potential to reignite war in Europe.

The chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Konrad Adenauer (depicted in this poster), had run afoul of the Soviets since 1949, chiefly for his successful campaigns to halt Allied denazification policies and his advocacy of German rearmament. He became an easy target for Soviet propagandists as tensions between East and West flared in the summer of 1961 when Khrushchev threatened to sign a separate peace with East Germany and to cut off Berlin from the West yet again. The immediate crisis was ultimately if uneasily resolved in August with the construction of the Berlin wall and a lasting stalemate.

In this poster, which strikes a triple blow against NATO, German rearmament, and Western sanctimony, Adenauer — labeled a self-righteous hypocrite and marked with a swastika — is depicted in the shape of an atomic bomb (note the three letters “A” on his shirt collar and cuffs) welcoming a menacing formation of American B-52 bombers flying eastward. The caustic, rhyming caption reads: “All peace-loving people know about these ‘heavenly powers.’”

This poster is the final one in a series of 15 by the same artist aimed against NATO and the rearmament of West Germany, indicating the extent to which these actions were perceived to be a threat. Much of the imagery from this series — the constant conflation of NATO with Nazism, for instance — echoes eerily with current Kremlin rhetoric. Even the specific topic of German rearmament has resurfaced as a Kremlin touchstone following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

![Связь прервана! / Sviaz' prervana! / [Connection interrupted!]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495222605.jpg?itok=6-0fxCDh)

Throughout its history, Soviet state atheism saw periods of stricter and looser implementation. After a lengthy period of relaxation following the ouster of Khrushchev, official hostility toward religion again began to intensify in the mid-1970s, aiming to temper what the state saw as a concerning resurgence of Russian Orthodoxy. While perhaps not as harsh as its predecessors, this campaign — which lasted until the run-up to the 1988 millennial celebrations of the Baptism of Rus’ — still led to the persecution of thousands of practicing Christians, Muslims, and others and to the shuttering of hundreds of places of worship. The anti-religious propaganda produced during this period was intended to be more conciliatory than it had been in the past and less directly critical of the pious. The aim was to convert, not to alienate. One common strategy, employed here, was to stress the incompatibility of science and religion. Starchikov comically depicts God and a few angels under assault by Soviet satellites as technological advancement and the pursuit of knowledge tear holes in their heavenly clouds and obscurantist lines of communication. Starchikov’s poster is part of a 1970s set of anti-religion images titled Razum protiv religii, “Reason Against Religion.”

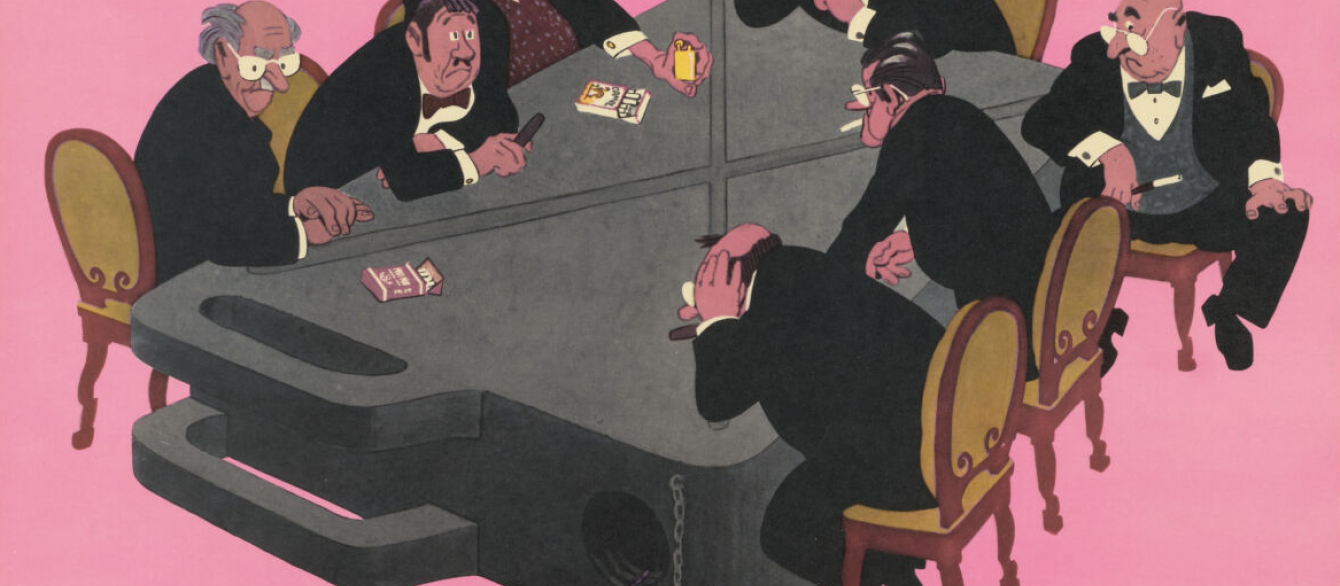

![Тебе вершки: воздай хвалу судьбе / Tebe vershki: vozdai khvalu sud'be / [If you got the smatterings, give praise to fate]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495352786.jpg?itok=sYSLrBAb)

Decidedly anti-capitalist visual propaganda was a staple of the Russian press that pre-dated the October Revolution. While the forms changed slightly over time — the top hat and tails giving way to trilbies and suits — the content remained the same: exploited workers brazenly and constantly swindled out of the fruits of their labor by the greedy bourgeoisie. In the era of “mature socialism,” such scenes were set nearly exclusively outside the borders of the Soviet Union. This poster — contrasting the wages above ground to the profits hidden below — is part of the 1977 series Kapitalizm bez maski, "Capitalism Unmasked,” a collection highlighting the ills of Western capitalism.

![Старые погудки антисоветской утки-дудки / Starye pogudki antisovetskoi utki-dudki / [The old tunes of the anti-Soviet duck-flute]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495222026.jpg?itok=PiveaWPA)

In this amalgamation of visual and verbal metaphors, the American military plays a charmed pipe of lies: The Russian word for duck, as in French, also means “canard” — hence, the officer’s instrument is called a “duck-pipe,” spouting anti-Soviet alarmism to conjure an ever-increasing military budget. The piper here is unaware that his ootka-doodka’s transmogrification of money into bombs spells impending, self-wrought doom. The poster is intended to spark Soviet awareness of ballooning U.S. defense spending and to sell that as dangerous warmongery, in stark contrast to Soviet calls for peace.

10. “Slippery Slope”

![Скользкая дорожка / Skol'zkaia dorozhka / [Slippery path]](/sites/default/files/styles/full_column_large_/public/2024-02/495222008.jpg?itok=TG_oNsmB)

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev launched the final large-scale campaign that would target drug and alcohol consumption in the Soviet Union. Public drunkenness was prosecuted, and the sale of alcoholic beverages restricted. While some posters from this campaign promote alternatives to alcohol such as fruit juice, the majority focus on the negative effects of alcohol and opiates: domestic abuse, heightened mortality, poor productivity, etc.

This poster, put out by the traffic police, or GAI (pronounced gah-YEE), returns literal meaning to the metaphor of a slippery slope with a car plummeting along a faceted cordial glass toward a horrific crash. Traffic cops, or gayishniki, served on the frontline of the campaign to end drunk driving. Their roadblocks drew the ire of Soviet citizens and they quickly became the butt of many jokes, for both their alleged stupidity and unwanted zeal. One rueful joke from this time goes: “All gayishniki ask, ‘Have you had anything to drink?’ But not a single one wants to know whether I’ve had anything to eat.”

Despite its extreme unpopularity, Gorbachev’s partial prohibition, which lasted until the dissolution of the Soviet Union (and some believe may have hastened it), did manage to decrease crime and mortality rates. But it did so at the cost of billions of rubles in lost revenue that would have gone to the state from alcohol sales.