Below is the first half of a two-part explainer, based on an extensive interview with Averbuch by our colleagues at Harvard's Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI) and originally published on HURI's website. Averbuch has scoured numerous archives, studying the photographs and correspondence of Ukrainian forced laborers in Nazi Germany, and has gathered them in an exhibit running until July 1 at Harvard's Fisher Family Common gallery, "Our Life Behind Barbed Wire: Photography From Ukrainian Ostarbeiters in Nazi Germany."

In this portion of the interview, Averbuch explains how Ostarbeiters imparted news and secret messages to their loved ones, finding creative ways to defy Nazi censorship. Part 2 of the interview — where Averbuch discusses what drew him to the subject and upcoming plans for the research — can be found on the HURI website.

I view and study the Ostarbeiters’ photography as part of Nazi propaganda. It was used as part of a powerful mechanism of the production and dissemination of false information, along with leaflets, posters, and the publication of pro-Nazi newspapers.

The authorities allowed the Ostarbeiters to correspond with relatives back home in the occupied territories and to send photographs. Writing letters was one of the few emotional outlets available to them, torn as they were from homeland and family. Ostarbeiters were instructed as to what could be mentioned or shown, and what was forbidden. As conscription relied both on luring volunteers and taking people by force, the Nazis’ aim was to use these letters and pictures as textual and visual propaganda — to facilitate the acquisition of slave laborers by promoting the idea of their “wellbeing '' or even prospering in Germany.

Annotated images on display at "Our Life Behind Barbed Wire," the exhibit at the FFC gallery.

Initially, the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda directed that camps where Ostarbeiters were located be visited by photographers, who would produce group photographs which were then given to the workers to send to relatives. This was an entirely controlled and staged process, as Nazi personnel themselves took the photos.

Later, Ostarbeiters were allowed to send photographs they had taken in nearby cities, in studios or by street photographers, or even in automatic photo booths. This was an ostensibly free process; but they were instructed on what imagery could be sent along with their letters and were also aware that whatever they sent would be subject to censorship. And if you, as an Ostarbeiter, knew that following these rules was the only way your relatives might see your image or get the merest information or just “sign of life” from you, you would probably follow them.

This is what makes interpreting this medium so tricky. On the one hand, you see people often smiling, in relatively nice clothing; on the other, you discern, or decipher, quite horrific messages about their actual conditions: imprisonment, forced labor, lack of food, humiliation, daily suffering, and violence. However, as my exhibit and overall project aim to show, these people, under harsh conditions, often managed to creatively escape the censorship and smuggle out information, conveying real news about the war and their life within the Reich.

When I think about these people’s lives, I often find myself trying to answer certain questions: what does it mean, and how does it feel, to be in captivity, far from family and homeland, alone and in danger, and to know that the only channel of communication with loved ones available to you — a channel you can’t refuse, because it’s the last one remaining — might be used against you, and against them?

The fact, moreover, that Nazi propaganda was so integrated into postal materials shows the regime’s awareness of how letter-writing and photography, which combine emotional affinity, visual transmission, and interpersonal trust, could promote a particular image of Germany and what it supposedly had to offer.

Ostarbeiters were well aware that all their letters would be subject to censorship. This is seen most vividly in their open reflections on the censorship in the letters themselves; in their instructions to relatives on how to write back in ways that would not elicit censoring; and in their attempts to encode information on how they were doing and how the war was going in the places where they were located.

Openly negative reflections were relatively rare in the texts of letters, but they did occur, even in less coded ways. More typically, though, adverse descriptions would be found in what was written on the backs of photos. Since the photographs were sewn onto letters, this decreased the chance that the censor would see what the Ostarbeiter-senders had written on the reverse side — often quite negative reflections. In general, we can put these artifacts into two categories. In the first, the texts (either the letters themselves, using whatever form of “encoded” writing, or the captions written on the backs of photographs and thus hidden from the censor’s eye) contradicted the idyllic-seeming photographs. In the second category are those instances where the photographs themselves managed to portray, or at least hint at, the less-than-ideal reality, refuting the favorable wording of the letters.

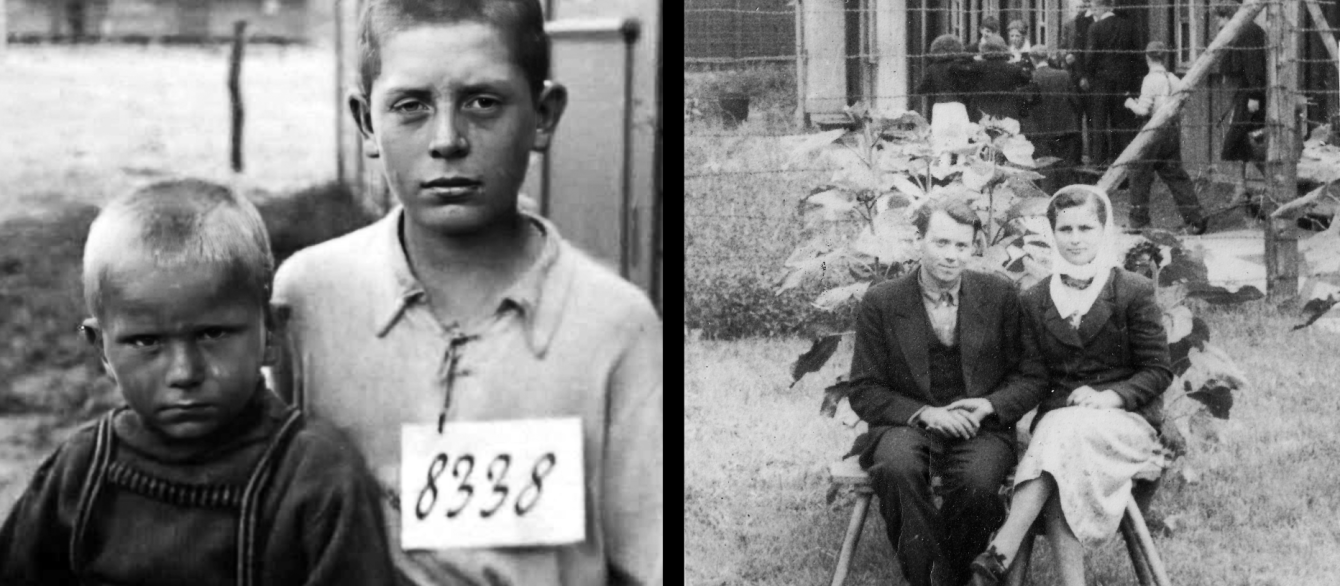

“My dear sisters, look at least at my shadow and imagine that I was your sister.” Olha Mamalyha, Putzig (now Puck), Poland. Camps were places of imprisonment, often surrounded by barbed wire or high fences, as in this photograph.

While we tend to think of censorship as something total, capable of checking all mail, there were not enough qualified staff for that, and the whole process was often quite chaotic. Especially after Germany began to retreat, and many of its occupational infrastructures, including postal facilities, started collapsing. Scholars estimate less than half of the post in this context was checked by censors. The authorities’ goal was to scare senders with looming punishment if they didn’t follow the rules, creating the discipline of self-censorship. This was quite successful.

How Ostarbeiters were treated at factories and big camps differed considerably from their treatment in the countryside or in German households, where they were employed either as singles or in small groups.

In the camps (devoted mainly to heavy industry and mining), relations were very much as they would be in a prison. Barbed wire, high fences, dogs, guards, restrictions on movements, food rationing, heavy surveillance — overall, a great deal of hierarchy and of segregation between Germans and Ostarbeiters. The authorities were particularly anxious lest interpersonal relations, or especially any sense of solidarity, emerge between German workers and Ostarbeiters. But we know of numerous personal contacts between them, some quite warm and human. I have encountered records of instances in which Germans helped Ostarbeiters by smuggling extra sandwiches or items of clothing to them. In some cases, Germans doing this were caught and punished.

This would explain the host of decrees, promulgated from the very beginning of the Ostarbeiter program, forbidding Germans to interact with Eastern workers. In their propaganda efforts, the authorities also took pains to demonize the “savage” Soviet people, from whom “civilized” Germans should keep their distance, and preferably avoid. And this jibed with Nazi “race” doctrine, which inculcated the menace of “racial impurity” in such relations. The Nazis believed that propaganda of this sort would enable them to accumulate millions of alien workers inside the Reich without the “threat” of their integration into German society.

However, when it came to employment as farmhands in the countryside, which mainly involved single Ostarbeiters or small groups of them, it was hardly possible to “quarantine” these workers away from the given German farmer’s household or otherwise avoid interpersonal relationships. At these locations, workers had more freedom of movement and better food and housing. It was still not, of course, ideal; often these places, too, were venues of abuse and violence, and there were cases in which Ostarbeiters fled these (naturally more escapable) households. But in general, the level of treatment was more humane than in heavy industry or big agriculture, as Ostarbeiters in this context inevitably came into close contact with families and the children thereof, often dining at the same table with them.

Another category of workers were female maids and nannies, whose recruitment was especially based on their “Aryan”-like appearance. For the task of caring for their children, the Germans preferred blond and blue-eyed, “Aryan”-seeming Ukrainians, who might be descendants of Germanic peoples that had resided in the territory of Ukraine. Drawing such a distinction between Ukrainians and other Eastern Slavs was clearly an example of the downplaying of “racial” principle for the sake of the Nazis’ practical needs.

“Mother, I was on my way to visit you, but it turned out to be too far, and I couldn’t get there. I must go back. I thought I would see Ukraine through binoculars, but I can’t see it. It’s very far.” Hanna Komisarenko, Thal, Austria.

Officially, German household heads were strictly forbidden to discuss news or politics with their Eastern workers; but in any case, one was far likelier to experience humaneness in this milieu. For instance, many Ostarbeiters reported, decades after their return, that when the war ended, their “masters” tried to convince them to stay in Germany with them. (Some historians interpret cases of late-war kindness as evincing the desire to be seen as a “good master” for “insurance” purposes, i.e., to reduce the possibility of revenge in case of German defeat.)

In short, we have to bear in mind that, however powerful the propaganda machine was, there were millions of Ostarbeiters and millions of relationships established over a four- or five-year period, as potentially different as the multitude of individuals involved.

Nazi propaganda was effective in particular in the first year of the Ostarbeiter program. When, subsequently, many letters and photographs made it possible to smuggle encoded information about what life was really like, the propaganda effect decreased. However, propaganda often relies on the overall atmosphere it creates by the sheer abundance of its messages, which sometimes have a hypnotic effect. Propaganda is not about rational thinking, but about pressuring and manipulating people — in this case, people who were on the verge of emotional and physical breakdown, starvation, etc. So it’s not just a matter of persuading, but also of “informational poisoning” — creating a false sense of a stable future, and trust. And of disaffiliation from the Soviet Union, and its army (where your relatives might be serving at the same moment).

Propaganda operates with simple slogans and catchy images. But after reading thousands of letters and seeing many photographs, I realize that people, even amid the disasters befalling them, were able to critically perceive these messages, to decipher them and draw their own conclusions, and to resist.

In general, I am convinced that people experiencing oppression, for example, under occupation, learn to see through propaganda and get to its subtext. And this is, by the way, quite relevant today, as many Ukrainians live under occupation, many with no choice but to stay where they are; and we should not be hasty to judge them, as the vast majority of us don’t know what it’s like to be in this situation — don’t know how we would survive.

The Ostarbeiters represent a considerable topic for contemporary Ukraine. Millions of families have a parent or grandparent who was taken to Germany for forced labor. The Ostarbeiter experience remains one of the country’s greatest personal and historical traumas, and there are a few projects dedicated to it. For Ukrainians, captivity is unfortunately not a rare historical experience. And creative reflections on forced labor in Nazi Germany pertain to a long Ukrainian tradition of artistic treatments of captivity dating back to the Tatar-Mongol era, as reflected in folklore of the pre-Khmelnytskyi period, and in later literary reflections, through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, up to the literary works by Ukrainian prisoners in the Gulag.

In the postwar Soviet Union, former Ostarbeiters were shunned as traitors and collaborators. A great number were sent to the Gulag upon their return to the USSR. Many would never be able to get an education, build a career, or start a family and have children. In a way, these people were victims of two totalitarian regimes, Nazi and Soviet, their lives scarred by both. Ostarbeiters and their stories are often dismissed because of this non-belonging. Many were silent for decades.

Many went through “filtration” upon returning (or being returned, often by force) to the Soviet Union — a formal evaluation of their loyalty to the Soviet regime. Many didn’t pass the filtration, and were sent into another imprisonment, this time in their homeland. Female Ostarbeiters give horrific accounts of their abuse by Soviet soldier-liberators, who treated these women as the ultimate traitors. The gendered aspect—the idea of a treacherous femininity, projected onto the Soviet-propagandized conception of Ukrainianness as treacherous in general — often resulted in revenge: humiliation, rape, and other violence toward the Ostarbeiters.

Filtration files are available at various archives. From them, you can get a sense of the mistrust and suspicion these people encountered upon repatriation, and how they suffered for it. Even if not imprisoned, it could shatter their lives. Many would be incapable of having children, as Ostarbeiters were often placed in dangerous industries (working with chemicals, for instance) that affected fertility. And many women had undergone unprofessional abortions in Germany, which likewise caused irreparable damage to their health.

Averbuch speaking with attendees at the opening of the exhibit.

If the letters of Ostarbeiters constitute a topic that has received at least some scant coverage in scholarship, their photography remains entirely unexplored. Moreover, due to the distinct propagandistic aspects of these photographs (still unpacked by scholars), investigating this contradictory visuality may appear to be an “awkward” activity, as what seems to be depicted is the “good life” these people supposedly lived in Germany, while German forces were destroying their homeland.

The negative image of Ostarbeiters as “collaborators,” disseminated both in the USSR and the West, was an effort of Soviet propaganda. In the past few decades, numerous studies have presented alternative perspectives on the Ostarbeiters’ experience. While many have concentrated on the living conditions they endured in exile, there has been less emphasis on reintegrating their voices, which remain largely absent, into Ukraine’s collective memory.

In Germany and the greater Reich, Ostarbeiters naturally lived in communities formed by their imprisonment conditions, as well as by linguistic limitations — they could communicate freely, in their own language, only with their countrypersons from Ukraine.

I often think of my project as a study of a subculture, one that consolidated amid harsh circumstances. This subculture was viable and highly creative. People wrote poems and songs; they maintained a cultural life within a very repressive system. They were in the same boat, and their creative expressions, including photography, are remarkable. The Soviet regime silenced these people’s voices, depriving them of their past and identity. Many report that, upon their return, they found that loved ones, threatened by the Soviet authorities, had burned the letters and photographs they sent, and that these loved ones likewise urged them to burn the diaries they had kept while in captivity. So, in a way, these people were not only deprived of their own voice, but also of the memory and recognition of their suffering.

There was, of course, a sense, a feeling — even more, an anxiety — of being rejected by your loved ones once you departed for Germany for this labor. This emerges very distinctly from the letters that time and again address the feeling of frustration, anger, and hurt if your family wasn’t writing to you. However, it was actually quite rare for family members to shun a person who had gone to Germany. Far more typically, if correspondence was not forthcoming, it was because of infrastructural breakdowns, incorrect addresses, or simply the death of relatives back in the occupied territories. This is precisely why letter-writing was so essential for the captives: they needed signs of life from loved ones, as much as the latter needed the same from them.

The condemnation of Ostarbeiters, especially after their liberation and return home, was inevitable. It was also fed by the Soviet regime, whose modus operandi in this (and so much else) relied on mutual denunciation, on making citizens fearful and mistrustful of one another. It was not only Ostarbeiters who underwent multiple humiliations and mistrust, but also the residents of territories under German occupation; these people had no choice but to live under the rule of the occupier, and to some extent “collaborate” with it. Unfortunately, Ukraine currently has a significant population living under occupation as well. Some have managed to escape it; some remain; but any of them can become targets of political suspicion and censure. We, as a free society, need to think about how we deal with these people and territories once they are liberated.

My research takes an individualized approach, aiming to understand, through case studies, how people under totalitarian regimes found creative ways to express themselves despite censorship. By examining the relationship between control of communication and attempts to evade it through metaphor and allegory, I hope to shed light on how individuals used both text and photography to challenge the stereotypes imposed on them.

Averbuch's exhibit on the Ostarbeiters' photography and correspondence will be displayed at the FFC Gallery until July 1, 2024. The event is cosponsored by the Davis Center and HURI.