UPD: The memorial for Prof. Graham will take place Jan. 27 at 4 p.m. in Cambridge.

This is an abridged version of a longer tribute; the full text can be found here.

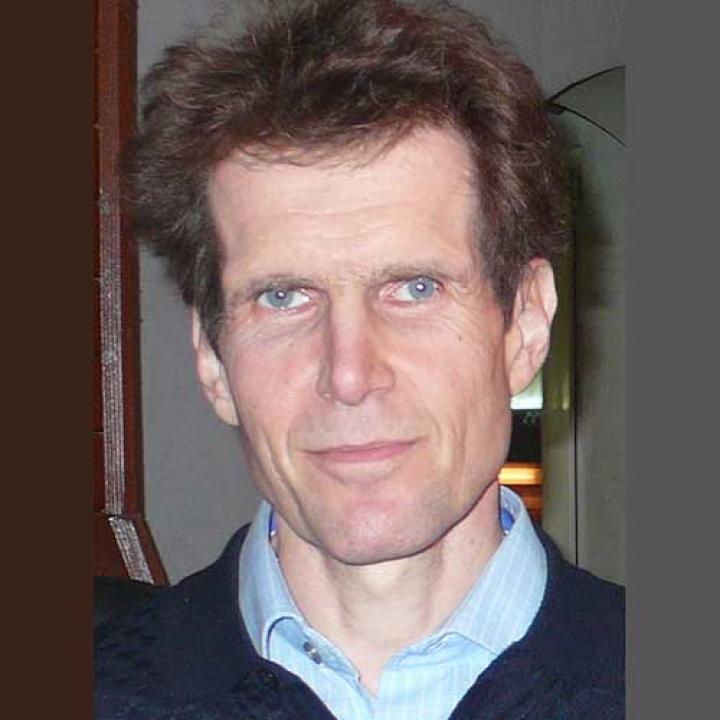

Loren R. Graham, a long-time associate of the Davis Center and one of the world’s foremost experts on the history of science and technology in Russia and the Soviet Union, died on Dec. 15, 2024, after a brief illness. He was 91.

Loren was born and raised in Indiana and attended Purdue University, receiving an undergraduate degree in chemical engineering in 1955. He then worked as a chemical engineer at the Dow Chemical plant in Midland, MI, where he soon decided that he did not want to devote his career to engineering. After a three-year stint in the U.S. Navy as a communications and intelligence officer, including deployments on warships during some of the tensest moments in the Cold War, he decided to pursue graduate studies in history, with an emphasis on the history of scientific and technological advances. He learned both Russian and French as a graduate student at Columbia, where he received a master’s degree in history and a certificate in Russian studies from the university’s Russian Institute (today's Harriman Institute) and then completed his Ph.D. in history in 1964. As part of his graduate research, Loren made his first trip to the Soviet Union in 1960-1961, when he was among the initial cohorts of U.S. graduate students and scholars included in the academic exchange program between the U.S. and the USSR that developed as a result of East-West détente.

Loren returned to Indiana for three years, accepting a teaching position in history at Indiana University before going back, in 1967, to Columbia as professor of history with a joint appointment at the university’s Russian Institute. In 1978, Loren moved to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he spent the rest of his academic career. Until his retirement some 35 years later, Loren held joint senior faculty posts in the history of science at both MIT and Harvard. For 46 years, he was associated with Harvard’s Russian Research Center (now the Davis Center) in various capacities, including many years on the center’s Executive Committee and one year (1995-1996) as the center’s acting director.

Loren was the author of 20 books and dozens of articles, mostly on the history, politics, and culture of science and technology in imperial Russia, the Soviet Union, and post-Soviet Russia. In his writing, Loren discussed the historical, political, and cultural dimensions of the Soviet experience with science, addressing questions that were taboo for scholars in the USSR itself. In the process, he was able to shed light on crucial features of the Soviet system, going well beyond science. His books included The Soviet Academy of Sciences and the Communist Party, 1927-1932 (Princeton University Press, 1967), Science and Philosophy in the Soviet Union (Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History (Cambridge University Press, 1993), Lysenko’s Ghost: Epigenetics and Russia (Harvard University Press, 2016), and Lonely Ideas: Can Russia Compete? (MIT Press, 2013).

Loren was dedicated to reaching beyond specialist circles when discussing topics related to his own expertise and general love of history. Much as he valued the opportunity to produce state-of-the-art scholarship, he also felt it was important to offer narratives suitable for the wider public. In 1986, Loren was closely involved in putting together the documentary “How Good Is Soviet Science?” for the NOVA science program. He served as on-screen narrator, examining the status of science and technology in the USSR and the potential for change under Gorbachev. His Moscow Stories (Indiana University Press, 2006), a collection of anecdotes and reflections on his experiences in the USSR and post-Soviet Russia over 45 years, conveys a deep admiration for Russian culture and great respect for ordinary Russians.

Loren was married to Patricia (Pat) Albjerg Graham for nearly 70 years. Pat also received her Ph.D. in history from Columbia (focusing on the history of U.S. public education) and went on to become a highly acclaimed professor of education and senior administrator at Columbia, Princeton, and Harvard, where she served as dean of both the Radcliffe Institute and the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Loren described the day that Pat was announced as the first female dean of a Harvard college as “the proudest day of my life.”

Loren and Pat spent a lot of time on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, specifically Grand Island, on the south shore of Lake Superior. In 1972 they bought the abandoned North Light Station and repaired and rebuilt the site; thanks to their efforts North Light Station was formally included in the National Registry of Historic Places in 1985.

As a scholar and part-time resident, Loren delved into the history of Grand Island and eventually published two books about the island and its history — A Face in the Rock: The Tale of a Grand Island Chippewa (University of California Press, 1995) and Death at the Lighthouse: A Grand Island Riddle (Arbutus Press, 2013). He also contributed to a 300-page guide entitled Grand Island and Its Families, 1883-2007 (Grand Island Association, 2007). Their time on the island also led them to collect a large set of antique prints, paintings, and photographs of lighthouses from around the world, which they later donated to the National Lighthouse Museum on Staten Island, New York, in 2018.

Loren received many awards and accolades during his academic career, including the George Sarton Medal from the History of Science Society for “a lifetime of scholarly achievement” in 1996. Despite his many accomplishments, he remained a remarkably humble, down-to-earth, amiable, generous, and kind-hearted person until the end of his life. He was revered by his many graduate students over the years, was a beloved fixture at the Davis Center, and was equally treasured at MIT, Columbia, and beyond. Everywhere he worked, he was a voice of reason and calm, a fount of penetrating insights, and a person of great integrity and good humor. He will be missed.