In the summer of 2020, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya emerged as the leader of a mass protest movement against Belarus’s authoritarian president Aleksandr Lukashenko.I use spellings of names and places that appear more commonly in English-language sources. These are generally transliterations from Russian, rather than Ukrainian or Belarusian. For example, I use “Aleksandr Lukashenko” and “Chernobyl” instead of “Alyaksandr Lukashenka” and “Chornobyl,” as the former are more familiar to English speakers. As the political newcomer gained international recognition for her activism, media highlighted her background as a mother and wife to jailed Belarusian activist Sergei Tikhanovsky. News outlets ran profiles with headlines like, “Tikhanovskaya: From Stay-At-Home Mom to Opposition Leader” and “How a Belarusian Teacher and Stay-at-Home Mom Came to Lead a National Revolt.”Stéphanie Fillion, “Tikhanovskaya: From Stay-At-Home Mom To Opposition Leader,” Forbes, September 4, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/stephaniefillion/2020/09/04/tikhanovskaya-from-stay-at-home-mom-to-opposition-leader/; Vivienne Walt, “How a Belarusian Teacher and Stay-at-Home Mom Came to Lead a National Revolt,” Time, February 25, 2021, https://time.com/5941818/svetlana-tikhanovskaya-belarus-opposition-leader/.

Tikhanovskaya reinforced this narrative by stressing her humble origins.Sarah Rainsford, “Belarus: The Stay-at-Home Mum Challenging an Authoritarian President,” BBC News, July 31, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53574014. But soon another aspect of the politician’s past captured international attention: the trips she made to Ireland as a child. Tikhanovskaya was one of nearly a million Belarusian children who traveled abroad through humanitarian aid programs for victims of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster.Katherine Butler, “Svetlana Tikhanovskaya: from ‘Chernobyl child’ in Ireland to political limelight,” The Guardian, August 11, 2020, https://web.archive.org/save/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/11/svetlana-tikhanovskaya-from-chernobyl-child-in-ireland-to-political-limelight; Jason Corcoran, “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary for Belarus Opposition Leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya,” The Moscow Times, August 25, 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20210528104958/https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/08/25/its-a-long-way-to-tipperary-for-belarus-opposition-leader-svetlana-tikhanovskaya-a71240; Elena Shalayeva, “European holidays for the children of Chernobyl. How an activist from Ireland responded to the call for help after the nuclear accident [Европейские каникулы для детей Чернобыля. Как активистка из Ирландии откликнулась на призыв о помощи после атомной катастрофы],” Current Time TV, April 26, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20210528105217/https://www.currenttime.tv/a/deti-chernobylya/31219911.html.

On April 26, 1986, a reactor exploded at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Soviet Ukraine, polluting huge swaths of territory with radioactive particles. Belarus and Ukraine were particularly hard-hit by fallout from Chernobyl. As information about the disaster’s dire health consequences spread, organizations across the globe offered aid to victims. Groups from Germany, Ireland, Italy, and the United States were among the most active.Astrid Sahm, “On the Way to a Transnational Society? Belarus and International Chernobyl Aid [Auf dem Weg in die transnationale Gesellschaft? Belarus und die internationale Tschernobyl-Hilfe],” Osteuropa 56, no. 4 (2006): 112. Local and foreign NGOs worked together to repair hospitals, train doctors, conduct medical examinations, and deliver food and medicine to disadvantaged populations.Maria Khudaya, “The Chernobyl catastrophe - a common pain [Чернобыльская катастрофа - боль общая],” Belarus’ v mire, July 1, 2002, 15–16.

Radiation hotspots resulting from the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant accident as mapped in 1996.

The Children of Chernobyl

The “Children of Chernobyl,” a catch-all term for kids who suffered from the effects of the accident, attracted particular attention, as their bodies absorbed more radiation than adults’.Kate Brown, Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019), 31. The most common form of foreign aid involved health trips, in which children traveled abroad for rest, recovery, and medical treatment.

The scale of foreign humanitarian aid to the Children of Chernobyl was impressive. In 2002, for example, a United Nations report described the health trips as “possibly the largest and most sustained international voluntary welfare programme in human history.”“The Human Consequences of the Chernobyl Nuclear Accident: A Strategy for Recovery” (UNDP and UNICEF, 2002), 62, https://web.archive.org/web/20190728221515/https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/strategy_for_recovery.pdf. But such assistance was also uneven: although Belarusian and Ukrainian youth both experienced psychological and physical health problems after the Chernobyl accident, the volume of aid to each group varied. Belarusian children like young Svetlana Tikhanovskaya received considerably more international attention than their Ukrainian counterparts, both in media coverage and material benefits.

A Puzzling Disparity in Foreign Aid

Although comprehensive statistics on all foreign aid to Belarusian and Ukrainian Children of Chernobyl are unavailable, various metrics reveal the stark difference in assistance to the two populations. Foreign news reports, for instance, emphasized the plight of Belarusian children over that of Ukrainians. After conducting a keyword search on the BBC website, I identified 105 articles and videos about the Children of Chernobyl that were published between 1998 and 2020. Of these, 57 focused exclusively on Belarusian children, and nine on Ukrainian children. (Nine articles referenced both groups, and 30 did not specify the children’s origin.) Belarusian children also benefited disproportionately from health trips to foreign countries. Italy accounted for around half of all health trips for the Children of Chernobyl; 72 percent of the children who traveled there were Belarusian.Ekatherina Zhukova, “Chernobyl brought Italy and Belarus closer together – their approach could do the same for other nations,” The Conversation, May 8, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20210528094448/https://theconversation.com/chernobyl-brought-italy-and-belarus-closer-together-their-approach-could-do-the-same-for-other-nations-95820; Nina Romanova, “I’ll take your pain,” Sovetskaia Belorussiia, August 8, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20210528094556/https://www.sb.by/articles/i-ll-take-your-pain.html.

Although both Belarusian and Ukrainian youth experienced psychological and physical health problems after the Chernobyl accident, the volume of aid to each group varied. Belarusian children received considerably more international attention than their Ukrainian counterparts.

This disparity in aid is puzzling for several reasons. First, although a greater proportion of Belarus’s territory was contaminated by radiation from Chernobyl, most people associate the disaster with Ukraine, where the plant was located. Second, Belarusian president Aleksandr Lukashenko was hostile to foreign charities, as he feared their connection to his political opponents. Third, Belarus was an authoritarian country subject to strict Western sanctions. Despite its problems, Ukraine was a democracy on a path to European integration.

Given these conditions, we would expect Ukraine to receive more foreign humanitarian aid to Belarus. So why did Belarusian Children of Chernobyl dominate the spotlight, while Ukrainian children sat on the sidelines?

Explaining Uneven Levels of Aid

I explored this puzzle in the dissertation I submitted in June 2021 for my MPhil in Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge. Drawing on primary and secondary sources in multiple languages, including newspaper articles, archival documents, government reports, and survey data, I found that differing political dynamics within the recipient countries—Belarus and Ukraine—led to divergent aid flows. In Belarus, foreign aid for the Children of Chernobyl was highly politicized; in Ukraine, it was not.

My research revealed that three main factors drove the high volume of aid to Belarusian children: opposition engagement, the efforts of an outspoken activist, and Lukashenko’s foreign policy strategy. Lukashenko downplayed the effects of the Chernobyl disaster, urging Belarusians not to “blow the problem out of proportion” and dismantling social welfare benefits for victims.Grigory Ioffe, Reassessing Lukashenka: Belarus in Cultural and Geopolitical Context (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 229; Adriana Petryna, Life Exposed: Biological Citizens after Chernobyl (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013), 4–5. Opposition activists responded by accentuating victims’ suffering, wielding images of sick children to convince foreign donors to support the Children of Chernobyl and condemn the Belarusian government.

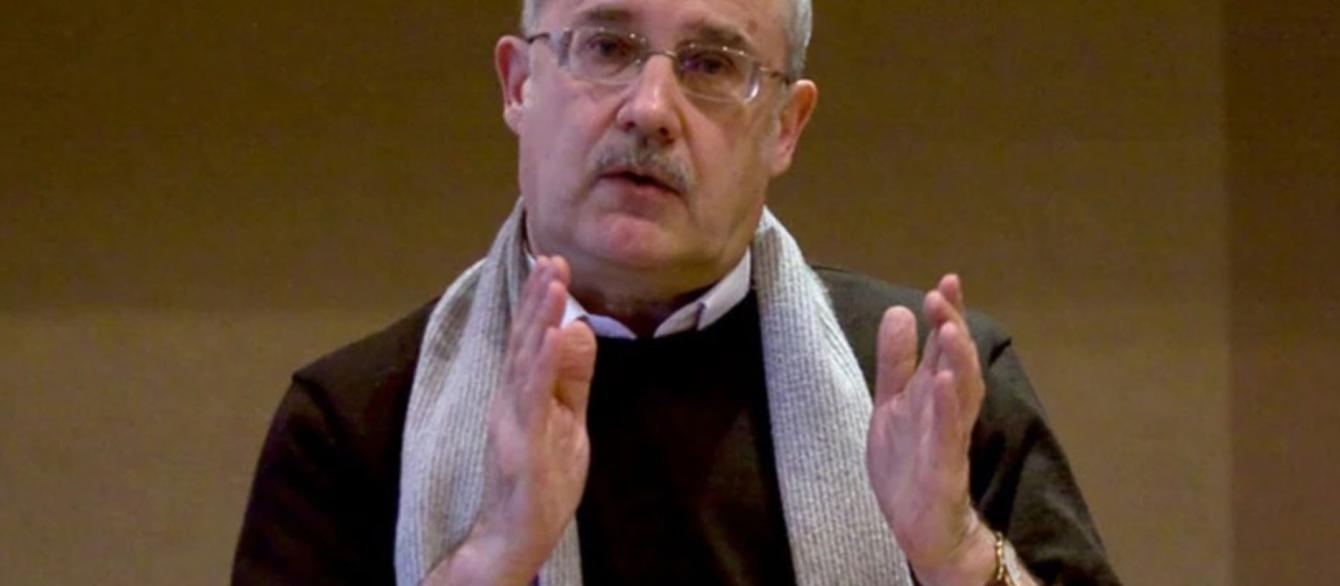

Gennadiy Grushevoy, an opposition politician turned charity director, was a particularly vocal critic of the Lukashenko regime. Grushevoy used his charisma and perseverance to build a vast network of foreign donors, even in the face of government repression.

Although Lukashenko restricted collaboration between local NGOs and foreign charities, he did not ban Children of Chernobyl programs outright. Rather than eliminating foreign humanitarian aid, the Belarusian president coopted it to serve his foreign policy goals. Chernobyl relief programs were one of the few initiatives permitted under Western sanctions; for Lukashenko, maintaining such programs was a way to counteract international isolation and reduce Belarus’s dependence on Russia.

Gennady Grushevoy, an opposition politician and later charity director, built a vast network of foreign donors to provide relief to victims of the Chernobyl disaster.

These three factors were absent in Ukraine, which explains why foreign donors did not flock to that country. While Chernobyl was an object of political struggle in Belarus, it was a point of consensus in Ukraine, where citizens united as nuclear victims. Unlike Lukashenko, the Ukrainian government maintained social protections for affected populations, reducing incentives for disgruntled Ukrainians to use the Children of Chernobyl to criticize their leaders. Furthermore, while foreign aid programs in Belarus benefited from Grushevoy’s activism, Ukraine’s aid community lacked a similarly energetic leader. Finally, as Belarus battled international sanctions, Ukraine tightened ties with its Western neighbors. Whereas Chernobyl cleanup was one of the few avenues for cooperation between European countries and Belarus, Ukraine had more options. Foreign donors concentrated their efforts on shutting down the Chernobyl plant and promoting democratic reforms. In Ukraine, the Children of Chernobyl were of secondary importance.

Repression and Aid: A Paradox

While most scholars of foreign humanitarian aid focus on the determinants of foreign aid within donor countries, my research highlights how recipients shape aid flows. I find that, paradoxically, a more repressive political system can lead to greater aid when both the recipient country government and its opponents view aid as advantageous to their goals.

But my work provides as many questions as answers. For example, can we extend my conclusions about the political drivers of humanitarian aid to other cases of natural disaster and conflict?

The political trajectory of Belarusian human rights activist and opposition politician Svetlana Tikhanovskaya raises questions about the long-term consequences of foreign aid programs for young participants.

Long-Term Consequences for Belarus

The Children of Chernobyl is also a topic ripe for further exploration. Svetlana Tikhanovskaya’s political trajectory in particular raises questions about the long-term consequences of foreign aid programs for young participants. Observers speculated that Tikhanovskaya’s summers in Ireland may have influenced her vision for a democratic Belarus. “I would like to think … that all those personal connections hundreds of thousands of Belarusian children made with families in other European countries also had an impact on changing the national mentality and, in some measure, their country’s future,” wrote an Englishman who hosted several Children of Chernobyl on health trips. “If I’m right then it would be a really positive, if totally unexpected, legacy of Chernobyl.Peter Webscott, “Belarus and the Impact of Chernobyl on Its Struggle for Freedom,” West Country Bylines (blog), August 31, 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20210531143412/https://westcountrybylines.co.uk/belarus-and-the-impact-of-chernobyl-on-its-struggle-for-freedom/.

Was he right? Can we draw a causal link between foreign aid programs and pro-democracy attitudes among young Belarusians? As any good scientist knows, correlation does not imply causation. But this is a question well worth asking, especially in light of contemporary Belarusian politics.

Today, Belarus is back in the headlines—this time for Lukashenko’s brutal crackdown on dissident journalists. The country’s future remains uncertain, but many younger Belarusians are demanding political change. Their motivations warrant a closer look. Given the large number of Belarusians who traveled abroad on Children of Chernobyl programs, foreign humanitarian aid may be key to understanding Belarus’s political development.