“This is going to be good,” I thought to myself as I opened the large archival file at a desk in the reading room of the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art. The file, number f. 2916, o. 2, d. 16, was the transcript of the discussion of the nomination of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s famous novella One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich for the 1964 Lenin Prize, the Soviet Union’s highest literary award. According to the log attached to the cover of the file, it had been examined by many researchers over the years, but I had never seen it cited.

After a few hours of poring over the discussion, I was puzzled. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is a chilling account of a single exhausting day in the life of a prisoner in a Stalinist labor camp. It was the most important literary work of Nikita Khrushchev’s “Thaw,” if not the entire Soviet period. Yet I was surprised to discover that the discussion of the Soviet writers who made up the literature section of the Lenin Prize Committee had relatively little to do with Solzhenitsyn’s harrowing description of the everyday degradations of life in the Gulag.

Rather, much of the writers’ discussion revolved around the future Nobel Prize winner’s portrayal of the character of Ivan Denisovich, an ordinary Russian war veteran from a peasant background. According to the novella’s critics, Ivan Denisovich was too passive. Rather than resisting the injustices of the camp, he accepted his fate and hoped simply to survive. For this reason, the Russian poet Nikolai Gribachev, a diehard Stalinist and Solzhenitsyn’s most vocal critic on the committee, argued that Solzhenitsyn’s portrayal of Ivan Denisovich was an affront to the Russian nation.

Solzhenitsyn? The famous Russian nationalist? Insulting the Russian nation? I tried to bend my mind around this seemingly absurd accusation.

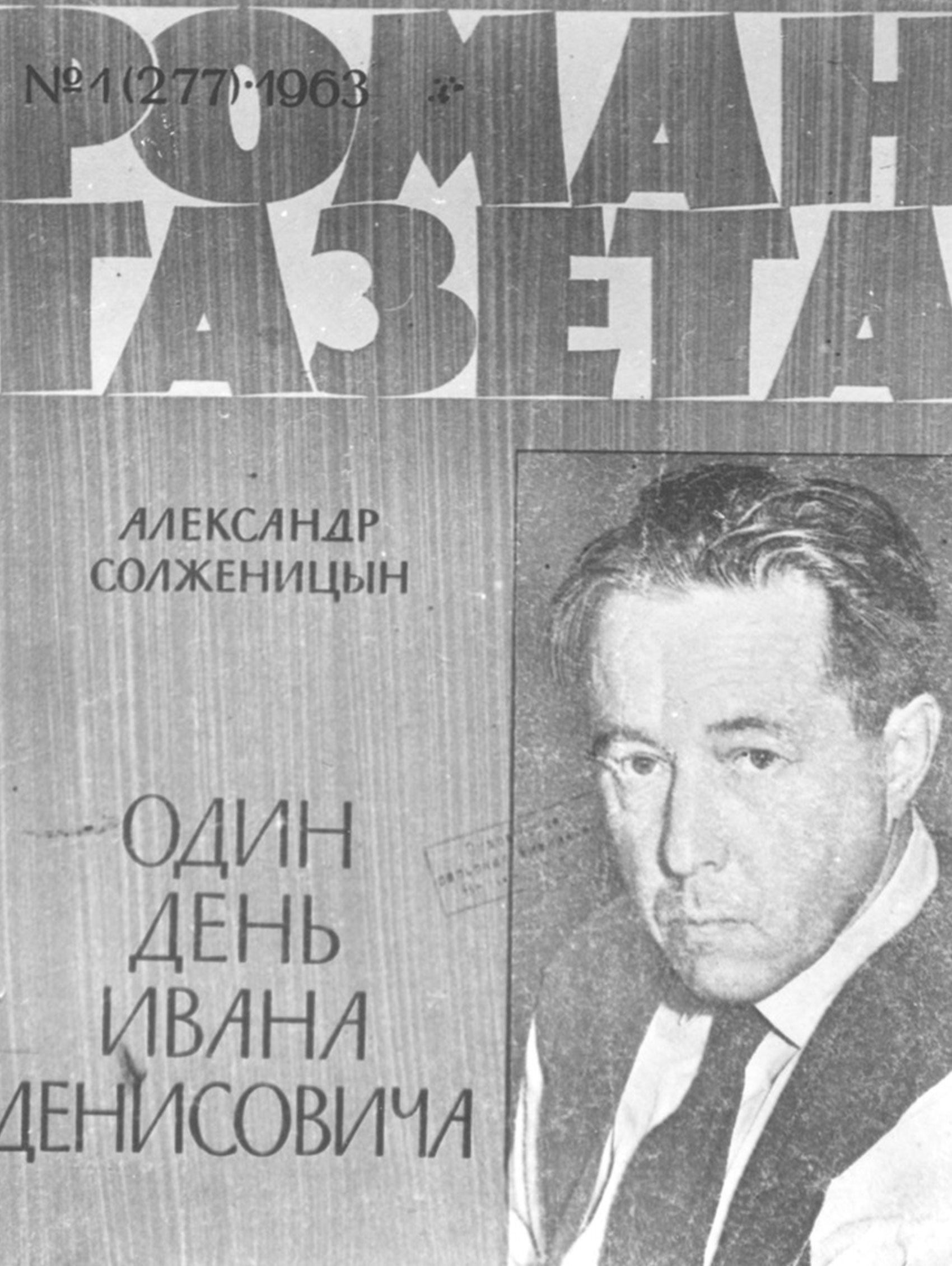

The One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich cover of Roman-Gazeta, 1963.

As I discovered as I read the transcripts of several subsequent meetings of the Lenin Prize committee, the charge that the character of Ivan Denisovich was insulting to the Russian nation proved to be one of the major arguments that eventually sunk the novella’s nomination for the Lenin Prize. In fact, the only Russian supporter Solzhenitsyn had in the literature section of the Lenin Prize Committee was the famed Russian poet Aleksandr Tvardovskii, who had published the piece as the editor of Novyi mir. The rest of Solzhenitsyn’s supporters were non-Russian writers.

I began to study more closely the arguments of Solzhenitsyn’s primary opponent, the Russian poet Gribachev. “Ivan Denisovich’s entire philosophy can be reduced to one thing—accommodation, survival,” he stated at the February 1964 meeting of the literature section. “Is this the true Russian character? Nothing of the sort. All of our history testifies to the rebellious spirit of the Russian people, which nothing could beat out of them,” he said, clearly alluding to Russia’s long history of peasant uprisings. So, for Gribachev, the Russian peasant was rebellious, even revolutionary.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn with the mistress of the house at Davydovo, “Matryona the Second,” January 31, 1968.

In the end, I came to understand that what I was reading in the transcripts was a showdown between Gribachev’s Stalinist conception of Russian identity, and Solzhenitsyn’s “new” conception of Russian identity—which was in fact, an old one.

At the second round of deliberations in April, Gribachev stated that Solzhenitsyn’s character reflected Western stereotypes about Russian peasants: “The is the ‘mysterious Slavic soul,’ as they call it abroad. ‘How do the Bolsheviks manage to rule? Because the Russian people are obedient, patient, the mysterious Slavic soul.’” Reading this, I had to laugh. Learning Russian as an American, I had heard plenty about the “mysterious Slavic soul.” Gribachev was not wrong to say that this common stereotype, which had its roots in nineteenth-century Russian thought, was prevalent in the West.

Indeed, the commonalities between Ivan Denisovich and prerevolutionary notions about the character of the Russian peasant turned out to be Gribachev’s main issue with Solzhenitsyn’s hero. A few days later, at the meeting of the full Lenin Prize committee, Gribachev stated, “Solzhenitsyn described in the novella the character of an old Russian peasant. There are no Soviet qualities in this character, in essence. […] Portrayed is an old Russian peasant type, and he should not be made into the Russian Soviet people.”

Gribachev was arguing that Russian peasants were, by their nature, revolutionary and pro-Soviet. In Gribachev’s view, Solzhenitsyn used the character of Ivan Denisovich as a Trojan horse to smuggle offensive, old-fashioned ideas about the Russian peasantry into Soviet Russian literature.

I began looking at other sources that could provide insight into the debate over One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich at the Lenin Prize Committee. Solzhenitsyn’s literary memoir The Oak and the Calf confirmed that Solzhenitsyn considered Ivan Denisovich’s peasant background central to the character—indeed, Solzhenitsyn believed that his editor Tvardovskii and Nikita Khrushchev supported the publication of the controversial work because they shared Ivan Denisovich’s “unchanging peasant nature.”

I found citations for Soviet literary criticism that appeared in the aftermath of the publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and began to study the critical response to it and Matryona’s House, another short work by Solzhenitsyn that appeared in 1963. It turned out that by 1963, literary critics had already begun to voice the same concerns that Gribachev raised at the Lenin Prize Committee. So, although this was rarely mentioned in the copious scholarship on One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, the novella’s portrayal of the Russian peasantry had been central both to Solzhenitsyn’s conception of the novel, and to the critical response.

In the end, I came to understand that what I was reading in the transcripts was a showdown between Gribachev’s Stalinist conception of Russian identity, and Solzhenitsyn’s “new” conception of Russian identity—which was in fact, an old one. Gribachev’s view reflected the Stalinist maxim that national culture should be “national in form, but socialist in content.” Russian peasants may wear bast shoes and embroidered blouses, according to this view, but their rebellious nature was 100 percent compatible with Marxism. Solzhenitsyn’s perspective, meanwhile, was influenced by nineteenth-century Russian thought about the peasantry and (as the story Matryona’s House makes clear) Orthodox Christianity. Solzhenitsyn sought to depict how humble and hardworking Russian peasants kept their heads down and endured Stalinism, just as they had endured serfdom and so much else.

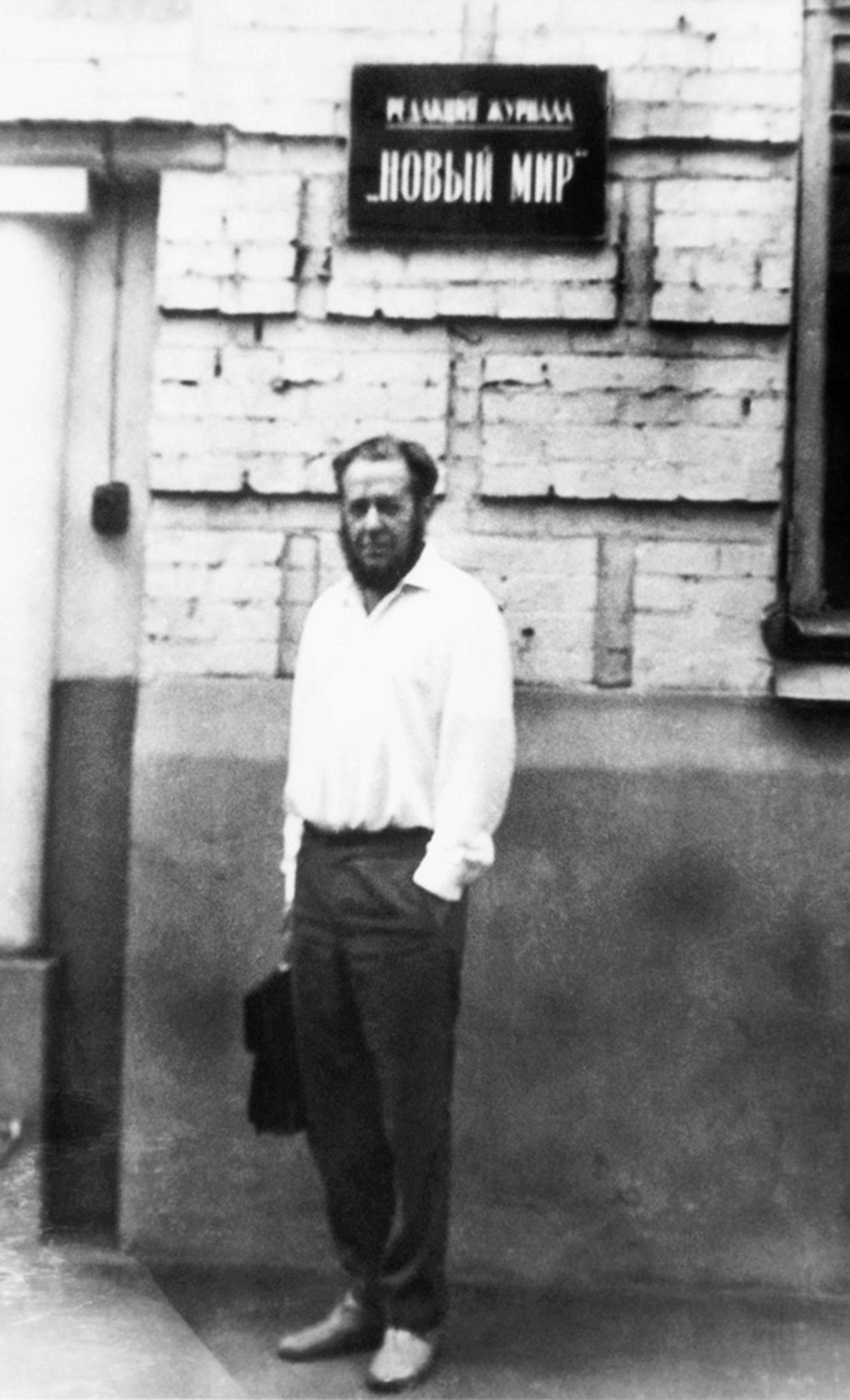

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in front of the editorial offices of Novyi mir, late 1960s.

In order to find out the details of the debate over One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, including the inspiring speeches in the novella’s defense made by the Kyrgyz writer Chingiz Aitmatov and others, you’ll need to read my article “Ivan Denisovich on Trial” in the Winter 2021 issue of Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. In the end, Solzhenitsyn’s opponents won the day. Right before the members of the Lenin Prize Committee voted, an article criticizing One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich appeared in Pravda, effectively destroying the novella’s chance of winning the prize.

But although Solzhenitsyn lost the prize, his ideas about the Russian peasantry proved to be quite influential. The debates at the Lenin Prize Committee can be considered the last gasp of the Stalinist conception of Russian peasant identity. Over the course of the 1960s, writers from a literary movement known as Russian Village Prose (many of them influenced by Solzhenitsyn) promoted a similar picture of the Russian peasantry as humble, hardworking, and morally righteous—the ones without which the Russian land cannot stand, as Solzhenitsyn famously wrote in Matryona’s House.

Reading the transcript of the Lenin Prize Committee’s discussion of Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich convinced me that debates over Russian national identity were as central to Khrushchev’s Thaw as discussions of the 1937 Terror and the Gulag. Indeed, as Solzhenitsyn’s novella shows, questions of national identity and the treatment of the peasantry were inextricably intertwined with broader discussions of the impact of Stalinism on the USSR.

That this seems surprising to us is reflective of the continuing urban bias in the study of a place that for the vast majority of its history was populated primarily by peasants like Ivan Denisovich. It also reflects, I think, the difficulties that U.S.-based scholars like me continue to face as they struggle to conceive of Soviet history outside Cold War paradigms that focused on the oppressive nature of the Stalinist system at the expense of other issues that were also important to our historical actors. In the end, the most satisfying thing about studying the debate over One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was that it proved to me that even some of the most familiar topics in Soviet history still have the capacity to surprise us.