Russia’s war against Ukraine shocked many scholars into rethinking their understanding of the world and the role of academia. As we affirmed a long year ago, the Davis Center stands with the people of Ukraine and with the many people around the world who are suffering as a result of Russia’s aggression. Like many institutions and individuals, we have sought ways in which we can support those who have been impacted using the resources we have at our disposal: the ability to educate; the desire to inform our networks of colleagues, students and friends about what is happening; and the chance to channel the energy of those who want to help Ukraine and mitigate the impacts of the war into productive and reputable projects. One such project is described below. We hope it inspires others to think about how they, as an individual or collective, can also make a difference to people who need help.

Daria Khitrova, Associate Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Harvard University, interviewed Yasha Klots, Assistant Professor of Russian at Hunter College, CUNY about the Tamizdat project he started.

“Manuscripts Don’t Burn” | Daria Khitrova in Conversation with Yasha Klots, Founder of Tamizdat Project, about Ways to Support Students Displaced by War or Repressions

Daria Khitrova:

On February 24 last year, as the first Russian missiles hit Ukraine, the explosions reverberated across American campuses, driving professors and students first into a shock, then into anger, tears, and a sense of powerlessness. Few of us teaching and studying Russia and Eastern Europe in America slept that night: in Ukraine, it was already morning. How did you feel then?

Yasha Klots:

You can imagine. The country where I was born and received my first academic degree invaded Ukraine as I was going home after teaching a night class on Andrei Platonov in my graduate seminar “Banned Books in Russia and Beyond” at CUNY. Across Fifth Avenue, where my students and I stood and talked for half an hour longer, the Empire State Building was lit blue and yellow by the time I got out of the subway in Queens. In Kyiv, the subway had already turned into a bomb shelter. The next day, I ran into students outside Hunter College, where the first antiwar protest took place in New York, half a block from the Permanent Mission of Russia to the UN on East 67th Street. I had to go to class and teach.

DK:

Did your teaching change when war began?

YK:

Not in what I taught that semester, but teaching itself has not been the same since. It became not enough. There has been a need to do more while universities in Ukraine are being bombed. While presidents of Russian universities are signing a letter in support of the war. While one of your students has not been able to reach family in Zaporizhzhia for several days. While another student is asking if her former classmate from Kyiv, now a refugee in Poland, can come to New York to continue studying. While students from universities in Russia you have worked with on a research project for two years are fleeing their homes with a backpack. You jump twenty years back and remember your first days as a graduate student in Boston, where you came with a stipend but without any political reason to do so whatsoever, other than an ambition to research Russian and East European émigré literature. Now you are a professor. Another student comes in, looks into your eyes, and demands: “What can I do? I want to do something! Give me something to do!”

DK:

Familiar question! What was your answer?

YK:

Years ago, I started the Tamizdat Project, a public scholarship initiative devoted to the study of banned books from the former Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. Now it is a nonprofit organization. Exploring the intricate stories of the first publications, reception, and circulation of “contraband” literature from behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War remains necessary but has become no longer sufficient. Resisting convenient parallels between the Soviet times and today, we have taken the initiative to support undergraduate students forced to leave home.

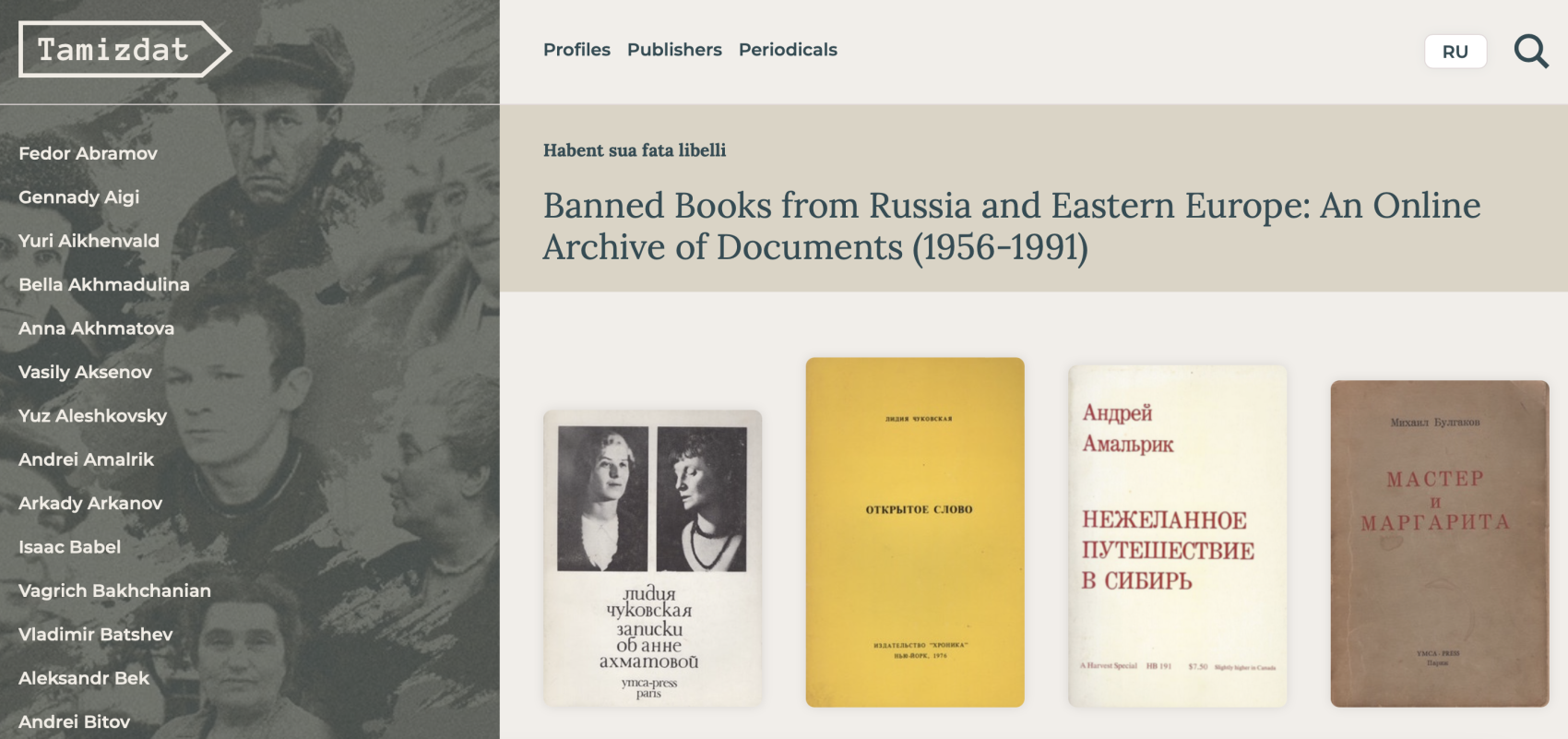

Home page of Tamizdat Project: tamizdatproject.org/en

DK:

Soviet or not Soviet, still it is quite a long tradition of exiled or self-exiled people from these three nations continuing influential cultural and intellectual work abroad, right?

YK:

Not only these three nations, of course. Tamizdat may be called differently in different languages and cultures, but it has existed, as a global phenomenon – and continues to exist – due to state censorship (take South America not so long ago, or China today, you name it). Our initiative, too, is inspired not only by the legacy of Soviet dissidents and their Western allies during the Cold War, but also by the history of the University in Exile (The New School), founded in New York in 1933 as a refuge for scholars escaping Nazism in Europe. The example of Alexander Herzen, an exile from tsarist Russia and founder of the Free Russian Press in London in the mid-nineteenth century, has also become especially poignant, not only in the context of Soviet-era tamizdat (which translates, literally, as “published over there,” or abroad), whose nature as a literary practice and political institution was both transnational and transcultural, but also in the context of today’s decolonization of the Slavic field. The motto of Herzen’s Russian publishing venture, “For our freedom and yours” (Za naszą i waszą wolność), coined by Joachim Lelewel, had been used by Polish rebels against Russian imperialism during the uprisings of 1830-1831. In 1968, seven Soviet dissidents walked out onto Red Square to protest the invasion of Czechoslovakia. The same Polish slogan appeared in Cyrillic, and with the inverted order of pronouns (“За вашу и нашу свободу”), on a banner held by one of the protesters. The protest lasted several minutes.

DK:

And yet we still honor these seven. Could you talk more about ways to support displaced students? Any way our readers can help as well?

YK:

Since February 24, 2022, many initiatives have been launched across American campuses to support scholars at risk. Very few, however, have been set up for undergraduate students, who have not yet established themselves in academia but have also been forced to leave home and now need to continue their education elsewhere. I know only of two such programs for undergraduate students in the U.S.: Students Affected by Global Events at Hunter College, and the Emergency Ukrainian Student Refuge and Eurasian Student Refuge programs at Bard.

To support the next generation of scholars when they most need it, on January 30, 2023, Tamizdat Project Inc. launched two online charity book auctions and a donation campaign to help students pursue academic careers in a safe environment. The Project’s main goal is to support students from Ukraine displaced by Russia’s full-scale war against their country. We also want to help those students from Belarus and Russia itself who are fleeing repressions because of their antiwar stance. The campaign will run through March 31. Anyone who makes a donation through Tamizdat online, regardless of whether it is large or small, is asked to indicate which group of students – Ukrainian, Russian, Belarusian, or any of the above – they want to support. Money raised through auctions of donated books will be channeled according to the author or donor’s wishes. The first section in our “Signed & Inscribed Books Auction” is “Books on Ukraine,” and it goes without saying that all funds raised from the sale of these editions will be spent on students from Ukraine. In general, we plan to spend most of the funds from both the donation campaign and our two book auctions to support Ukrainian students, who have been forced to continue studying abroad for reasons that cannot be compared to those of students from Russia and Belarus.

Contributors to Tamizdat Project's "Signed & Inscribed Books Auction." Left to right, top row: Vladimir Gandelsman, Maria Stepanova, Alla Gutnikova, Alexander Genis, Vitaly Komar; bottom row: Vladimir Sorokin, Polina Barskova, Svetlana Alexievich, Masha Gessen.

DK:

I myself have made a bid on one of Lidiia Chukovskaia’s Tamizdat editions. Is there anything else you wanted to highlight about the Tamizdat project?

YK:

Thank you! Our Rare Books Auction features a variety of first editions of “contraband” literature from the former USSR and books by émigré authors, some of them signed or inscribed (e.g., Joseph Brodsky’s Less Than One). Most of these works were banned, censored, or never submitted for publication in Russia and Eastern Europe but smuggled out abroad and first published elsewhere, with or without their authors’ knowledge or consent, years or decades before seeing the light of day at home already during or after perestroika. We are very grateful to everyone who has donated these rare editions to us and thus contributed to our cause! Today, these books remind us that freedom and education know no boundaries. The goal of this auction is to let the old emigration help today’s refugees, much as we wish no such effort was ever necessary.

Our Signed and Inscribed Books Auction consists of nearly 300 titles signed or inscribed by over 100 contemporary writers, translators, artists, and academics specifically for our cause. We are joined by the Nobel Prize Laureate Svetlana Alexievich, director of Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute Serhii Plokhii, award-winning poets Maria Stepanova, Linor Goralik, and Polina Barskova, prose writers Boris Akunin and Vladimir Sorokin, and stage director Dmitry Krymov, rapper and “foreign agent” Noize MC, to name but a few. All of them are now living and working abroad. It is an honor for us to share these authors’ faith in young talents, in students who will also write their books in the future, if only they are given a chance to continue studying now.

DK:

Wow, this is truly an all-star team!

YK:

It is! But apart from the two book auctions, Tamizdat Project has also launched an online donation campaign called “Manuscripts Don’t Burn.” Funds raised through our initiative will help students from Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus pay for tuition and living expenses while studying in the U.S. Tamizdat Project will work with the American colleges and universities that have admitted them to make this goal a reality. By the time our auctions and donation campaign close on March 31, we plan to send out a call for applications, so that undergraduate students already admitted to American universities or still waiting on their admissions letters can let us know about themselves, their needs and current circumstances. We anticipate having enough time to help them start studying in Fall 2023, or even the summer. While tuition and housing rates vary greatly between universities, our goal is to support at least 20 students.

DK:

I find it very inspiring and convincing that you and your team seem to focus on very concrete tasks, meeting people where they are and trying to address their specific needs.

YK:

It is impossible to overlook just how many students right now are in need, especially if you are a professor. A year into the war, Tamizdat Project has welcomed new volunteers, including several students from universities in Russia, some of whom consider themselves – in fact, are – Ukrainian, despite carrying a Russian passport. They are contributing to the project not only for purely academic reasons, but also to help others under far worse circumstances at the moment. They hope to see them safe and studying, even if far from home.

DK:

Good luck with your work. It’s so important that we find ways in which we can bring our expertise to bear in helping those who have been affected by this war, and this project is truly inspirational. Please let me know how I could help (other than bidding on Chukovskaia’s book!)