This is an excerpt from an article originally published by Foreign Affairs, co-authored by Vladimir Dubrovskiy and Yuri Danilov.

Since he returned to office in January, U.S. President Donald Trump’s aggressive outreach to Russia has marked a stark shift in U.S. foreign policy. Ending years of isolation of the Kremlin, the Trump administration has offered numerous concessions to Russian President Vladimir Putin, raising hopes among some Western observers that the United States might be able to bring about an end to the war in Ukraine after more than three years of fighting. So far, although Russia has shown an interest in engaging with Trump, there is little indication that it is prepared to wind down its military operations. But even if the administration’s efforts succeed in bringing the Russian government to the negotiating table, there is a far larger obstacle to achieving peace: Russia’s dramatic internal evolution since the war began.

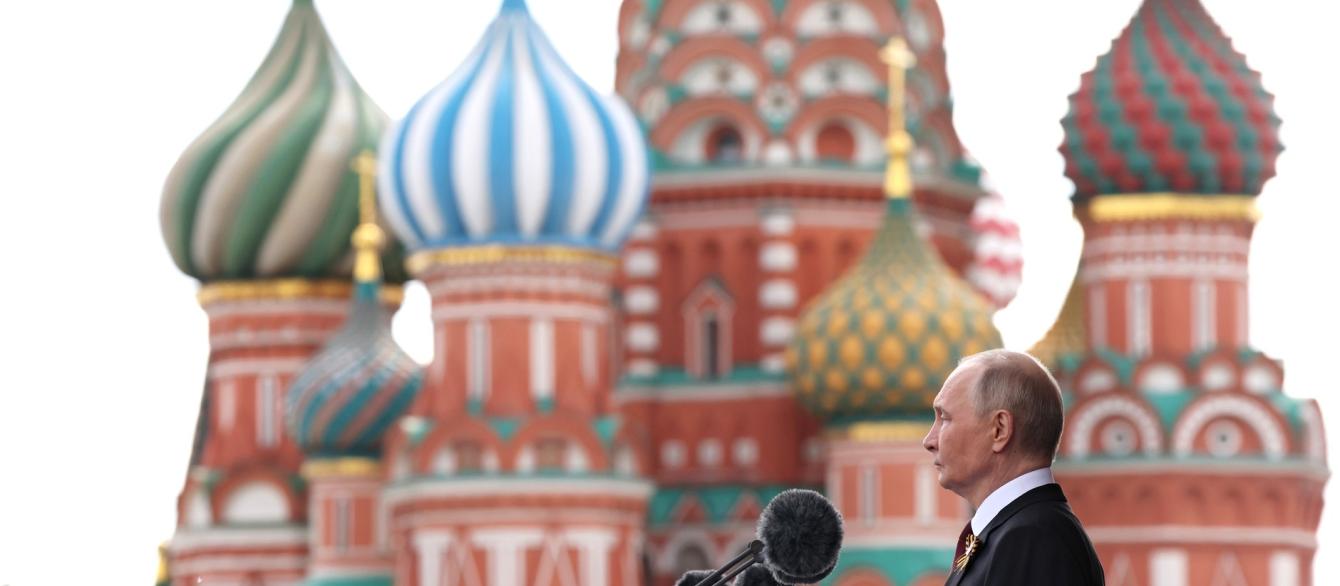

The war in Ukraine is central to Putin’s legitimacy, leaving him no rational incentive to end it voluntarily. At least since the end of 2022, the Kremlin has portrayed its war in Ukraine as a “war with NATO,” and confrontation with the West has become a key element of the regime’s ideology. To truly end the conflict, therefore, will likely require little short of a change of regime in Moscow — and one driven by actors within Russia who neither benefit from the war nor align with Putin. The current U.S.-led effort to jump-start peace talks has largely set aside the more crucial question of a long-term strategy toward Russia, both under Putin and after Putin.

Already well before 2022, the character of the Putin regime had changed significantly, as Putin moved away from the West. For years, the Kremlin had been building an ultraconservative, revisionist ideology centered on anti-modern values. After 2012, when Putin returned to the presidency, the Kremlin began tightening its grip on Russia’s elites, embracing an archaic militarism, and widening its repression of civil society. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and especially over the past year, however, that evolution has gone much further. Putin had expected a quick and cheap victory, not a protracted war; the situation has forced him to accelerate the restructuring of Russia’s political, economic, and social systems to tighten his grip on the nation. Along with the progressing militarization of the Russian economy, these changes have created severe tensions within the regime.

The United States ignores these internal changes at its peril. Rather than preparing for a postwar future of renewed relations with the United States and Europe, Putin has put Russia on a slippery slope of self-reinforcing and perpetual conflict with the West. If the regime gets its way over the next three to four years, Russia could arrive at a sociopolitical equilibrium that looks less like a capitalist authoritarian country with private-sector elites and more like a North Korean–style militarized autocracy. For the Kremlin, such an equilibrium could help it withstand even major challenges to its rule, as Pyongyang did during a devastating economic crisis in the 1990s. Moreover, given Russia’s large size and military strength, this kind of transformation could also pose profound risks to global security.

Yet Putin’s bid to remake the Russian state has also created new vulnerabilities for the regime. The Russian economy has become deeply imbalanced, with the country’s overwhelming dependence on oil revenues to support war-related fiscal expansion. Especially amid sinking global oil prices, this has made the Russian budget especially vulnerable to further sanctions. Moreover, tensions are emerging among Russian elites as a result of Putin’s efforts to push aside existing business leaders, bureaucrats, and others in favor of loyalists who adhere to the regime’s ideology or at least pay lip service to it, such as war veterans. To prevent Putin and his inner circle from consummating this transformation, the West will need to exploit these vulnerabilities. But this will require applying more economic and military pressure on Russia while also sending signals and offering incentives to potential elite dissenters — those most affected by the Kremlin’s rapid and forceful transformation of Russian society and who are potentially capable of stopping it.