On May 31, Kazakhstanis commemorate the victims of political repressions and the famine of 1932–33. A new book by Sarah Cameron, The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan (Cornell University Press, 2018), draws on years of archival research and oral interviews with survivors and their descendants.

The book has received a number of awards from academic associations, but more importantly, it has had an impact on the burgeoning public discourse on the famine (Asharshylyk) in Kazakhstan. Cameron’s scholarly account is helping this discussion evolve and develop analytical depth.

"[With] its staggering human toll, the Kazakh famine was certainly one of the most heinous crimes of the Stalinist regime," says Cameron. "Yet this famine has remained hidden from view both in Kazakhstan and in the West. Major narratives of the Stalin era mention the Kazakh famine only in passing, and until recently, a lot of the disaster's major events and factors were not well known." The Kazakh language version of the book launches on May 31, 2020.

Transcript

Terry Martin:

So very happy to have Sarah Cameron with us today. Great turnout here, a tribute to the interest in her book.

Terry Martin:

Sarah got her PhD from Yale University. She's now at the University of Maryland. I was just talking to her about, with her colleague Misha Dolbilov, one of the best Russian history programs, you know, departments in the country now with Misha and Sarah.

Terry Martin:

The book that she's going to talk about today, The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan, came out in 2018. We should have people selling the book here, right.

Speaker 3:

Yeah, we have the coupon.

Sarah Cameron:

Yeah, I'm [inaudible 00:00:43], yeah.

Terry Martin:

Oh, okay. Excellent.

Terry Martin:

In 2018. It's won a stunning amount of awards, won two awards from ASEEES, another one from the Ethnicity Studies-

Sarah Cameron:

ASN.

Terry Martin:

Which is a tribute to the book and, in my opinion, well-deserved. So we'll have a treat in her giving a presentation on that, for those of you that haven't read the book, for those of you that have, you can ask all of your questions when she's done.

Terry Martin:

And I just wanted to mention that she's working on a great new project on the desiccation of the Aral Sea, so we'll have her back in five or six years, as historians work slowly.

Sarah Cameron:

Yes.

Terry Martin:

So, Sarah, thanks for coming.

Sarah Cameron:

Okay. Thank you so much, and thank you to Nargis and to Terry for the invitation. I'm so pleased to be here and so pleased to see so many of you. It's great to have so many people interested in the history of Kazakhstan.

Sarah Cameron:

So today I'll be speaking about my recently published book on the Kazakhstan famine of the 1930s, and I'd like to begin by sharing a memory by a survivor of the famine. Wherever possible, I placed accounts by Kazakhs at the heart of my book, and it's their story above all that I seek to honor and to tell.

Sarah Cameron:

In the early 1990s, [Zh. Abishuly 00:02:08] spoke about his memories of the Kazakh famine. He said, "I was still a child, but I could not forget this. My bones are shaking as these memories come into my mind."

Sarah Cameron:

During the famine, activists with the Soviet regime had stripped Abishuly's family of their livestock and grain. His father's relatives had fled Soviet Kazakhstan entirely, escaping across the border to China. For those who remained, Abishuly concluded, hunger was "a silent enemy." He remembered the arba, the horse-drawn cart that collected the bodies of the dead, dumping them in mass burial grounds on the outskirts of settlements. During World War 2, Abishuly would go on to fight on the front lines for the Red Army. Nonetheless, he concluded, "surviving the famine is not less than surviving a war."

Sarah Cameron:

As Abishuly's recollections reveal, the period of 1930 - 1933 was a time of almost unimaginable suffering in the Soviet Republic of Kazakhstan, a vast territory in the heart of Central Asia, wedged between Russia and China. Maybe I don't need to show a map with this audience, I always do.

Sarah Cameron:

A massive famine claims the lives of a million and a half people, roughly a third of all Kazakhs perish, and it also transforms the territory of Soviet Kazakhstan approximate in size to Western Europe. As hunger set in, over a million starving refugees from Kazakhstan fled neighboring territories as well as China. They create a regional crisis. Some never return to Kazakhstan, and today's significant diaspora of populations of Kazakhs, many of those who fled during the famine, exist in the countries that surround Kazakhstan.

Sarah Cameron:

Prior to the famine, most Kazakhs practiced pastoral nomadism. By that I mean, and here you can see a shot from the 1920s of a Kazakh nomad. By that I mean that they carry out seasonal migrations along pre-determined routes to pasture their animals, sheep, horses, camels, among others. The famine forces Kazakhs to sedentarize, to abandon the economic practice of nomadism, and this shift, this forced sedentarization, leads to very far-reaching and painful shifts to Kazakh culture and identity.

Sarah Cameron:

And its staggering human toll, the Kazakh famine was certainly one of the most heinous crimes of the Stalinist regime. Yet this famine has remained hidden from view both in Kazakhstan and in the West. Major narratives of the Stalin era mention the Kazakh famine only in passing, and until recently, a lot of the disaster's major events and factors were not well known.

Sarah Cameron:

My book seeks to recover the story. It does so using a wide range of sources in Russian, but also sources in Kazakh as well. It begins with the famine's roots in the last decades of the Russian empire, and it follows the republic through the tumultuous years of the imposition of Soviet rule, Stalin's attempt to consolidate his hold over the steppe, and it concludes with the republic's slow road to economic recover after collectivization and the post-famine years of the 1930s.

Sarah Cameron:

I argue that the Kazakh famine was the result of Moscow's radical attempt to transform the nomadic peoples of the steppe who were known as Kazakhs and a particular territory, Soviet Kazakhstan, into a modern Soviet nation. I find that through the most violent means, the Kazakh famine creates Soviet Kazakhstan, a stable territory with clearly delineated boundaries that it was an integral part of the Soviet economic system.

Sarah Cameron:

I also find that it creates a new Kazakh national identity that largely supplants Kazakhs' previous identification with a system of pastoral nomadism. In the famine's aftermath, Kazakhs begin to think of themselves as a national group as opposed to a social group or one oriented around a system of pastoral nomadism.

Sarah Cameron:

The creation of a specifically Soviet Kazakh nationality was actually in fact a goal of Stalin's efforts to transform the steppe. Through equipping non-Russian groups, such as Kazakhs, Ukrainians, and others with their own territories, languages, and bureaucracies, Moscow sought to make them into modern Soviet nationalities and integrate them into the collectivist pool.

Sarah Cameron:

But in many other respects, as I'll draw out today, Moscow actually fails to achieve its goals. Ultimately neither Kazakhstan nor Kazakhs themselves become integrated into the Soviet system in precisely the ways that Moscow had originally hoped. In fact, the scars from this famine would haunt the republic throughout the remainder of the Soviet era and shape its transformation into independent nation in 1991. Indeed, in Kazakhstan today, the famine remains a largely forbidden topic, due in part to Kazakhstan's close relationship with Russia. The publication of my book has inspired intense debates about the meaning of the Soviet past and the nature of modern Kazakh identity.

Sarah Cameron:

Nearly every major news organization in Kazakhstan covered the book's release. Dozens of Kazakhs wrote to me to tell me stories of the horrors their families had endured during the famine. An op-ed that I wrote to publicize the book went viral in Kazakhstan and to my great horror, had 115,000 hits of me spliced in doing various things that I didn't actually do. The Chairman of the Senate who is now the President of Kazakhstan, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, commented on the book on Twitter, so you can see that here, and more recently, the book featured prominently in a demonstration by the Kazakh diaspora in Times Square.

Sarah Cameron:

So it's very, very interesting reaction which is still ongoing.

Sarah Cameron:

So my talk today is going to proceed along a couple of different lines. First, I'd like to tell you a little bit about how I came to the story of the Kazakh fame. What it was like to research this project, and why I believe that we don't hear about the Kazakh famine in the West. Then I'm going to turn the question of how and why the Stalinist regime came to implement such destructive policies. I'll talk about what collectivization looked like in Kazakhstan and how famine began. Finally, I'll conclude with the discussion of the consequences of the famine for Kazakh society, and I'll offer some thoughts on how the story of the Kazakh famine might revise our understanding of violence, modernization, and nation building under Stalin.

Sarah Cameron:

So, how did I come to this story? I stumbled upon the story of the Kazakh famine in part by accident. I had gone to Yale to get a PhD in Soviet history. When I was there, I got really interested in the history of the Soviet East. I believed it was a lot less explored than the history of the Soviet Union's West. I decided to make Kazakhstan the focus of my research efforts, and I went to Kazakhstan to begin learning Kazakh. While I was there, I started flipping through elementary school textbooks to learn more about Kazakh history. I noticed that these textbooks talked a lot about a famine, a devastating famine, that hit Kazakhstan during the 1930s, and I was startled because I was being trained in this field of Soviet history and I'd never heard of this famine.

Sarah Cameron:

I realized that this was a huge story, one which was incredibly important on a human level. Some, a third of all Kazakhs die in it. But also one that had really major implications for how we understand the nature of Stalin's rule and Kazakhstan today. And I began work on a topic.

Sarah Cameron:

Over the years, I've had some time to think about why the story of the Kazakh famine has come to be marginalized in the West, and I think I've come to a couple of answers. First I think, in the West, I think to a certain extent the marginalization of the Kazakh story illustrates how we're still struggling to incorporate the Soviet East into our understanding of Soviet history. Soviet history is often thought of as European history, but of course the Soviet Union was not just a European power. If you look at a map, on the most basic level, of course it's an Asian one too. And if we over stress the Soviet Union's European nature or if we neglect its Eastern half, we ultimately end up with a distorted view of what it was about.

Sarah Cameron:

Collectivization, the event that triggers famine in Kazakhstan, has often been framed as a struggle to extract grain from the peasantry, but if we turn to its Eastern half, we see that it was also about the struggle to transform nomadic peoples like the Kazakhs from a system of long distance animal herding to a network of meat packing combines and slaughterhouses that would produce meat for the market,

Sarah Cameron:

The major trigger for the famine in Kazakhstan is collectivization. This was part of Stalin's scheme to help the Soviet Union industrialize, to boost the agricultural production, to catch up to the capitalist West. And of course at the same time that famine comes to Kazakhstan, it afflicts other regions of the Soviet Union, most notably Ukraine and parts of Russia.

Sarah Cameron:

A long-running and very polemical debate has focused on the question of whether the Ukrainian famine was used by Stalin to punish Ukrainians as an ethnic group. And in the West, in part due to the efforts of an active Ukrainian diaspora, the story of the Soviet collectivization famines has focused largely on Ukrainians. So a second reason for the marginalization of the Kazakh story might be this long-running debate over the Ukrainian famine. With this heated debate, it's come to seem at times as if famine only occurred in the Ukraine, but of course this is not an accurate depiction of the story.

Sarah Cameron:

For one, many Russian peasants suffered. There are parts of Russia that had high levels of famine mortality. And it's actually Kazakhs that had the highest death rate of any group during collectivization.

Sarah Cameron:

Third and finally, I think the fact that Kazakhs were nomads is an important part of why this story has been neglected. Most nomadic societies are oral rather than literary societies. They tend to leave fewer traces in the written record. It's more challenging to uncover their stories. And the stories that we do, sources that we do have about nomadic peoples are often filled with assumptions, particularly the assumption that nomads are backwards.

Sarah Cameron:

This is why I worked so hard in my book to incorporate sources that were produced by the party or the state, such as memoirs or oral histories, and tried as much as I could to tell the story through the voices of Kazakhs themselves. And I think if we look historically, we can find that we've often been quick to dismiss violence committed against mobile peoples. We rationalize it as part of a process necessary to civilize so-called backward peoples. In the US, we need only look to our ongoing struggle to recognize, for instance, the scale of the crimes committed against Native Americans for an example of such a pattern.

Sarah Cameron:

When the Kazakh famine is mentioned in the scholarly literature, it's often referred to as a miscalculation by Stalin, a tragedy, a misunderstanding of cultures. But such depictions, I would argue, downplay the disaster's very violent nature, and seem to stress or imply that the Kazakh famine originated from natural causes, which of course it didn't.

Sarah Cameron:

I show in my book, there's nothing inevitable about this famine. Pastoral nomadism is not a backwards way of life, but rather it was a highly sophisticated and adaptive system. Nor can the famine itself be attributed to a simple miscalculation by Stalin as such depictions would seem to suggest.

Sarah Cameron:

In fact, Moscow receives very clear warnings about the perils of settling the Kazakh nomads, and Moscow's sweeping efforts to transform the steppe through collectivization and industrialization clearly anticipate the cultural destruction of Kazakh society.

Sarah Cameron:

So turning to the second part of my talk of what was Kazakhstan as a place and a society like on the eve of Soviet rule, and how did these conditions lead to famine? The Soviet Republic of Kazakhstan was created from disparate parts in 1924. It was an immense territory. You can see the map again. It was approximately the size of Western Europe, or to use another measurement, four times the size of the state of Texas. It has a sharp continental climate, hot summers, cold winters, was very arid and prone to drought.

Sarah Cameron:

And in the book I spend some time looking at the environmental features of the Kazakh steppe, which are also quite important to the story as I'll bring out. As you can see from the map, the yellow areas on the map, much of the Kazakh steppe is classified as a semi-desert or desert. There are more fertile zones in the North and also in the Southeast. And I bring this out to stress that Kazakh's practice of pastoral nomadism is an adaptation, actually, to these distinctive features, environmental features, of the steppe, particularly the scarcity of good pasture land and water. And pastoral nomadism had been the predominant way of life in the steppe zone for over four millennia.

Sarah Cameron:

I'll give you just a couple shots of what this way of life looked like, what pastoral nomadism looked like. I always like this image because it has baby camels in it. This is in Western Kazakhstan, some shots of nomadic life amongst the Adai, a Kazakh clan. And in these photos, I think you get a sense of first the isolation of the landscape. Also how important animals are to nomads' everyday existence. They made a lot of their clothing from animal skins, animal skins were also important in making the yurts that you can see here, the mobile dwellings that they use.

Sarah Cameron:

You'll notice in the photos I'm showing you, there's not really any cattle. Cattle are a later introduction to the steppe. The last two actually come from the Museum of Natural History in New York, so they have photos about Kazakhstan as well.

Sarah Cameron:

Pastoral nomadism, however, is not just an economic strategy, a way of making use of the steppe's scarce resources. It's also a crucial source of identity. Historically in the steppe, the practice of pastoral nomadism had often determined who was Kazakh and who was not.

Sarah Cameron:

In the late 19th century, there are shifts to this system. When the steppe is under Russian Imperial rule, over a million peasants from European Russia settled the Kazakh steppe. Their arrival makes Kazakhstan into a multiethnic society. It provokes important shifts to nomadic life, shifts to Kazakhs' diet, to their migration routes.

Sarah Cameron:

I explore these changes in greater detail in my book and I argue by taking this kind of longer view of collectivization, I show that actually the legacies of Russian Imperial rule were also a contributing factor to the famine. They shaped kind of the intensity of what the Soviet regime actually did.

Sarah Cameron:

Russian Imperial rule alters the nature of nomadic life, but crucially it does not erase it. Kazakhs adapt their practice of pastoral nomadism to the challenges of peasant settlement, and on the eve of Soviet rule it's nomadism, not being part of the national group, that remains the defining feature of Kazakh identity.

Sarah Cameron:

In the initial years of Soviet rule, the period 1921 to 1928, also known as NEP, the New Economic Policy, Moscow takes a contradictory approach to ruling the republic. Some programs work to support nomadism, other programs work to undermine it. Party experts and bureaucrats at this point really struggled to understand, actually, what they should do with nomadism.

Sarah Cameron:

The Kazakh steppe, the nomads who lived in it, this was a place that did not have clear parallels in the Marxist/Leninist categories that they brought with them. If we look at Marxist/Leninist theories, Karl Marx first predicts that socialist revolutions are going to occur amongst workers. Lenin then of course radically modifies some of Marxist's ideas, and he predicts that a socialist style revolution might occur amongst peasants. But neither of these two men gave a whole lot of thought to how socialist style revolution might occur amongst a totally different social group, pastoral nomads.

Sarah Cameron:

So party experts in this period begin to ponder a series of questions. Did nomads actually have classes in the way that settled societies did, and if so, how did these classes actually function? Economically? Could pastoral nomads speed through the Marxist/Leninist timeline of history and be transformed into productive factory workers?

Sarah Cameron:

Indeed, for some, the seeming absurdity of bringing a socialist-style revolution to this republic which was dotted with nomads and camels led one prominent Kazakh cadre, you can see him here, Sultanbek Khojanov, to circulate a joke, “You can’t get to socialism by camel.”

Terry Martin:

[inaudible 00:18:55]?

Sarah Cameron:

You can't. Yeah, you can't get to socialism by camel. That's what he said at the time. It also might have been slightly colored by the fact that he had just lost his position and been kicked out, so there's that element to it, too, but I take his comment, actually, as one of the titles of my book chapters, and I ask, "Can you get to socialism by camel?"

Sarah Cameron:

This was an issue that party experts were wrestling with in this period. You know, was nomadism backwards, or was it in fact a modern way of life, something compatible with socialism? Should it be preserved in socialist style modernity?

Sarah Cameron:

Given their plans to make Kazakhs into a modern Soviet nation, should this defining element of Kazakh culture ... was that part of their nation building project? Should it be eliminated? Should it be retained? And so on.

Sarah Cameron:

Entangled with all of these debates and these questions was the issue of the republic's environment. If you think back to that map I just showed you of all those arid zones. You know, could a specifically socialist state overcome the limitations that Kazakhstan's arid landscape seemed to place on human activity, or actually nomadism the only way to use this landscape?

Sarah Cameron:

Initially, most party experts associated with the republic's commissariat of agriculture, they argued actually in fact that nomadism was the only way to use this landscape. And some, even in this period in the 1920s, gave very specific warnings. There's one here, which often contemporary Kazakhstani historians of the famine love to quote. Sergei Shvetsov, he gives a very ... he gives kind of a prediction, almost, of what would happen.

Sarah Cameron:

In 1928, there is a severe shortage of grain. That triggers a shift in policy. Stalin declares the onset of the first five-year plan, the modernization scheme that I mentioned earlier in my talk. Aspects of Kazakhs’ practice of pastoral nomadism, specifically its distance from markets, its tendency for frequent fluctuations in animal numbers, begin to bring this way of life into clear tension with the proposals for more rapid industrialization that begin to circulate during the period.

Sarah Cameron:

Those who had supported keeping nomadism in some fashion, like Shvetsov, they're denounced. A separate group of experts belittle the assertion that the Kazakh steppe’s arid environment might place certain limits on human activity. They argue that settling the Kazakhs is going to free up large portions of land, and they argue that those lands, many of them could be turned over to grain cultivation, and increase the republic's portion of grain.

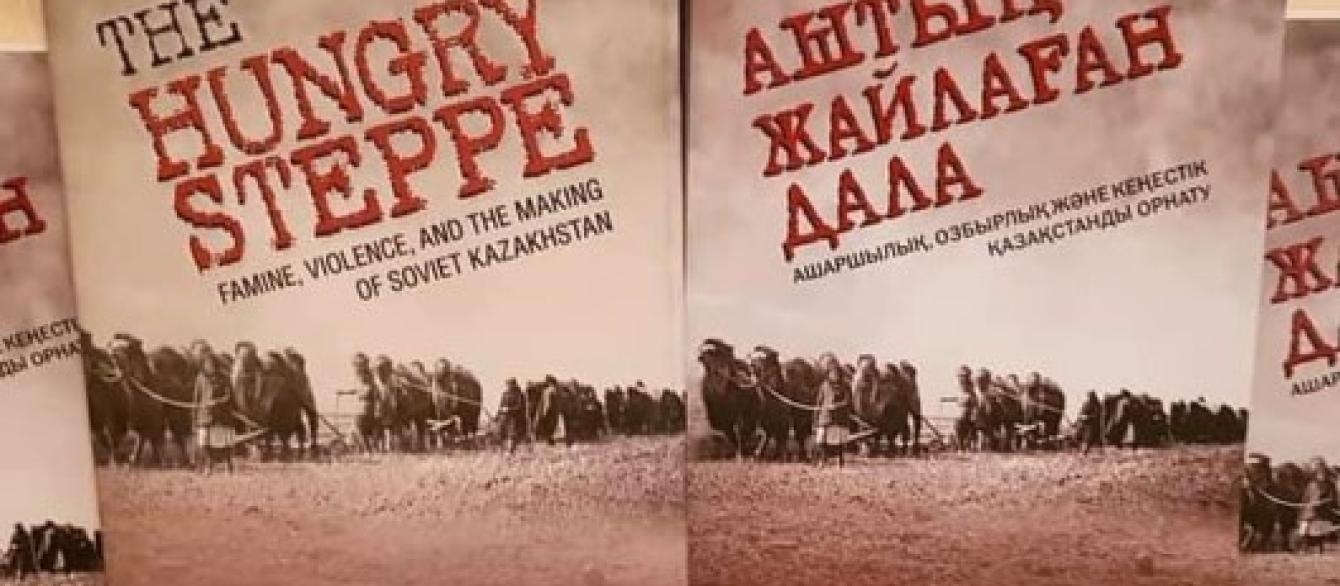

Sarah Cameron:

Here you can see, this image is on the cover of my book. You can get the sense of what collectivization looked like in Kazakhstan.

Sarah Cameron:

At the same time they were transforming many of these arid ... wanted to transform many of these arid fields into grain fields. They argued that animal husbandry would be transformed, that they would create large state farms that would focus on livestock breeding.

Sarah Cameron:

And, as I mentioned, another goal that they had in this period was the creation of a specifically Soviet Kazakh nationality, and so the language of Soviet nation-making serves to further legitimize and reinforce the importance of a shift to settled life. They declare nomadism to be incompatible with contemporary culture, such as schools, hospitals, telegraph connections, and the language of Soviet nation-making starts to reinforce the party's war on a social category, nomad.

Sarah Cameron:

And throughout the famine, we can see these categories, the category of Kazakh and the category of nomad, they serve overlapping and mutually reinforcing goals for the party's assault on nomadic life.

Sarah Cameron:

In 1928, the war on nomadism begins and it escalates with the launch of forced collectivization in the winter of 1929, 1930. It was led in Kazakhstan by this person, Filipp Goloshchyokin. Goloshchyokin is a very interesting character, also for the ways that he's been remembered after the famine and in Kazakhstan today.

Sarah Cameron:

He had originally been trained as a dentist, but I guess he found exciting revolution to be much more interesting than dentistry. So he joins the Bolsheviks early, prior to 1917. He gains a lot of renown in the Bolshevik party prior to Kazakhstan because he was known for his role in the murder of the tsar's family.

Sarah Cameron:

Beyond Goloshchyokin, as I draw out in the book, the local level implementation of collectivization hinges heavily on Moscow's partnership of local cadres, many of whom were Kazakhs. And the promotion of native cadres into the lower level bureaucracy forms a crucial element of Moscow's efforts to create ... to form the Kazakhs into a national group.

Sarah Cameron:

And in a strategy purposefully designed to shatter old allegiances and sow violent conflict in the Kazakh Awul, or nomadic encampment, Moscow actually empowers Kazakhs themselves to make some of the most crucial choices in the collectivization campaign. For instance, empowering them to decide who should be considered an exploiter, how much grain to confiscate from them, and so on.

Sarah Cameron:

As I found in my research, the efforts of these local cadres are crucial. They shape the scale of the violence, its intensity, but also its character, including which groups win out and which groups lose.

Sarah Cameron:

In the winter of 1930, famine begins. In Kazakhstan, like other parts of the Soviet Union, Moscow anticipates that collectivization is going to result in considerable loss of life. This human toll is seen as a necessary byproduct of the imperative to transform the region.

Sarah Cameron:

But Moscow did not anticipate the scale of the Kazakh famine. A number of unintended consequences soon emerge. Animal numbers plummet rapidly as the regime struggles to come up with a system to take the place of pastoral nomadism. Animals that are socialized in pens for the first time begin to contract diseases. They don't have fodder for the animals. And in 1931, the predictions of many experts who had said that this is a difficult place to institute settled agriculture, the predictions of those experts come to pass. There's a severe drought that worsens the effects of collectivization, and it depends Kazakhs' descent into hunger.

Sarah Cameron:

There are wide-ranging popular revolts during this period. Some of the Soviet Union's largest, actually. During collectivization, they envelop large portions of the steppe, and by July 1932, a report by Kazakhstan's commissariat of agriculture finds that Kazakhstan had, "fully lost its significance as the Soviet Union's main livestock base." The situation inside Kazakhstan becomes increasingly desperate. Many nomads enter into flight.

Sarah Cameron:

The republic itself begins to empty out. Ultimately, about 20% of the republic's population flee, more than a million people. As you might imagine, it's rather difficult for me to find photos of the starving during this period. This was not something that the party wanted to be known about. You also have to be careful because just the Ukrainian case, there are some fake photos floating around. But these ones, I'm quite confident in their authenticity. You can see people fleeing here.

Sarah Cameron:

You'll notice most of these people, they seem to be better dressed. You know, they've got warm clothes. So I would guess that these people are probably first wave refugees, because if you look at the sources who are describing the later waves of refugees, when the famine is really at its heart in the winter of '32 to '33, they are absolutely unanimous in emphasizing the poverty, the indigence, of these people. They have no warm clothing. They have nothing.

Sarah Cameron:

This transitional stage of Kazakhs' supposedly adopting a settled life, that's how the party framed a lot of the refugee crises, officials argue that it demanded extra vigilance. The party intensifies its assault on nomadic life. They declare fantastical plans to settle the Kazakhs ever more quickly than before. Moscow in this period closes the republic's borders. They shoot thousands of starving Kazakhs on the Sino-Kazakh border. And in a strategy explicitly modeled upon a technique that was used against starving Ukrainians, several regions of Kazakhstan were blacklisted. That essentially entraps starving Kazakhs in zones of death where no food could be found.

Sarah Cameron:

Along the republic's railway lines, travelers report encountering scenes of horror. They say, "living skeletons with tiny child skeletons in their hands, begging for food." Many people turned to substitute foods to survive in this period. They remember eating wild grasses or combing through fields to collect the rotting remains of the harvest. Others turned to cannibalism.

Sarah Cameron:

Duysen Asanbaev, a famine survivor, remembers, "Suffering was not leaving our heads. Our eyes were full of tears." Disease such as typhus, smallpox, cholera, tuberculosis, they began to spread. And the steppes' relative under-development begins to magnify the disastrous effects of collectivization.

Sarah Cameron:

In 1934, the famine itself finally comes to an end. This was reached in part through a certain amount of good luck, excellent weather, good harvest in '34, as well as increased attention by Moscow to problems revealed during the famine's course, such as the spread of disease.

Sarah Cameron:

The society that emerges from this famine is transformed, however. More than a million and a half people, roughly a third of all Kazakhs, perish in this famine. Those who survive the famine describe a feeling of trauma. Ibragim Khisamutdinov, who lived through the famine as a young boy, saw starving Kazakhs dying in the streets on his way to school. More than 50 years later, he noted, "To this day, I can hear the desperate cries of the dying and their calls for help."

Sarah Cameron:

In important ways, the famine precipitates and enables a far-reaching demographic transformation of the republic during the Soviet era. Moscow builds a forced labor camp on Kazakh's former pasture lands. During World War 2, the republic becomes one of the major dumping grounds for exiled peoples. More than a million deportees arrive. Kazakhs become a minority in their own republic. They don't constitute more than 50% of the population in Kazakhstan again until after the Soviet collapse.

Sarah Cameron:

In the aftermath of the disaster, nomadism as an economic practice was eliminated. Kazakhs are forced to become a sedentary society. Nationality, not pastoral nomadism, became the most important marker of Kazakh identity. Those Kazakhs who survived become integrated into the party-state. They join collective farms, enter educational institutions, or join communist youth organizations. So paradoxically, even as the Kazakh famine devastates Kazakh society, it creates opportunities for other Kazakhs to pursue education and upward mobility.

Sarah Cameron:

Given these results, I believe that the famine should cause us to look differently at the nature of Soviet modernization, nation-building, and violence under Stalin. And here I will offer a few concluding thoughts.

Sarah Cameron:

First, on the subject of violence under Stalin, Moscow’s sweeping program of state-led transformation clearly anticipates the cultural disruption of Kazakh society. And there's evidence to indicate that the Kazakh famine fits an expanded definition of genocide.

Sarah Cameron:

There is no evidence to indicate that Stalin planned the famine on purpose or sought to destroy all Kazakhs. As I brought out, many of the disastrous major consequences, from the refugee crisis to these massive outbreaks of disease, they're actually counterproductive to the regime’s interests, and they were unexpected consequences of the collectivization campaign. Nonetheless, the Kazakh famine should upend some of our assumptions about Soviet rule.

Sarah Cameron:

It's assumed that the Gulag represented the extreme of suffering in Stalinist society, but starving Kazakhs are actually expelled from their land at the height of the famine to make room for the construction of this forced labor camp in Central Kazakhstan, and they die from hunger and disease outside the gates of this camp while prisoners labor within.

Sarah Cameron:

The literature has stressed the central place of the Soviet Union’s west in the genealogy of Stalinist violence, a view popularized by Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands and several other books. My book, however, shows that the spectrum of violence under Stalin was far broader than previously believed, and that the Soviet East also generated important practices of social control.

Sarah Cameron:

The case of the Kazakh famine also holds important findings for the long-running debate over the Ukrainian famine that I mentioned earlier. Many existing explanations for the Ukrainian famine no longer make sense once you put the Kazakh famine into the picture. More broadly, I would argue the Kazakh case forces us to re-think some of the linkages that we have made between state-sponsored violence against particular ethnic groups and assumptions and attitudes in the Soviet state.

Sarah Cameron:

On the question of Soviet modernization, though it had notable success, in important respects, the project of Soviet modernization fell desperately short of its goals in Kazakhstan. Collectivization is an economic catastrophe across the Soviet Union, but nowhere were its effects more disastrous than in Soviet Kazakhstan. Prior to the famine, Kazakhstan had been the Soviet Union’s most important livestock base, but the republic loses 90% of its animal herds over the course of collectivization.

Sarah Cameron:

Despite the assertions of many Soviet experts that Soviet power would "conquer nature," we see over the course of the famine that Moscow really struggles to remake the arid steppe as it wished. And actually, you can see echoes of this in the post-famine years. Agriculture continues to be a very difficult enterprise in this region.

Sarah Cameron:

We see echoes of this in Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands program, for instance, and then later in the droughts, sandstorms, and crop failures that plague the steppe in the post-World War 2 period. Thus, as the example of the Kazakh steppe illustrates, environmental factors shape the nature of Soviet development.

Sarah Cameron:

Overall, I believe that the example of the famine should cause us to look at the nature of Soviet modernization differently. Some scholars have argued that the Soviet Union carried out a striking leap in state capacity and mobilization during the interwar period. But the Kazakh case reveals that the contours of this leap were uneven, and they look quite different in Kazakhstan than they did in parts of the Soviet Union’s west.

Sarah Cameron:

With regards to the question of Soviet nation-building, the case of the Kazakh famine reaffirms the centrality of nation-building. Moscow’s project of molding certain groups like the Kazakhs into modern Soviet nationalities, even as it underscores Soviet nation-building's destructive power. As I show in greater detail in the book, the Kazakh famine took its peculiarly destructive shape not in spite of the Soviet's nation-making efforts, but partly because of them.

Sarah Cameron:

Soviet ideas about nationality, such as the belief that nationality was connected to territory, served to justify and support the regime’s murderous actions. The crisis embeds nationality as the primary marker of Kazakh identity, a goal of Moscow’s nation-making efforts. Kazakhs begin to think of themselves as a national group.

Sarah Cameron:

But as I have stressed, this was an incomplete transformation. It did not eliminate alternate forms of Kazakh identity entirely. One of the most lingering and pervasive stereotypes about Kazakhstan, I think, is that Kazakhs are totally Russified. That they lost their culture entirely under Soviet rule. This is even captured in a popular joke. An Uzbek asks, “How can I become a Russian?” And he is told, "Oh, you need to become a Kazakh first."

Sarah Cameron:

And I would argue ... you've heard the joke, yeah. I would argue that this is really not true. If you look closely, that their culture is not totally destroyed. To give you one example, Kazakhs’ allegiances to various clans ... a clan is an important feature of nomadic life, they were transformed by the famine. They're divorced from their origins in the system of pastoral nomadism, but they continue to exert an important influence on Kazakh life in the post-famine years. They change as Kazakhs move away from kin members, but they continue to impact Kazakh life.And in Kazakhstan today, actually, I would argue, that nomadism has not disappeared. It has been refashioned as a kind of usable past, something that's Kazakhstan's post-Soviet leaders have used in the service of their nation-building project.

Sarah Cameron:

Various state-sponsored projects stress the innovative and sophisticated nature of the nomadic societies that ruled the steppe prior to the Russian conquest. I will give you one example. In the 1960s, Soviet archeologists find the remains of a Scythian warrior in a burial mound. Scythians are the first known nomadic empire. They ruled the steppe in the first millennium BCE. And today in Kazakhstan, this warrior has become known as The Golden Man. He's become known now for his gold-plated dress that he was buried in. He has become a very important state symbol, and if you pass by the Kazakh embassy in Washington, DC, you can see a statue of the Golden Man outside.

Sarah Cameron:

Today, however, the Kazakhstani government remains reluctant to address the issue of the famine. The famine remains a partially forbidden topic, a phenomenon that is due in part to Kazakhstan's close relationship to Russia, and Kazakhs' own investigation into their famine, which simultaneously created a new Kazakh identity even as it devastates Kazakh society and transforms Kazakh culture, remains an unfinished project.

Sarah Cameron:

Thank you.

Terry Martin:

Thanks, Sarah. That was quite a tour de force. You really did get an entire book into 30 minutes.

Terry Martin:

While you're ... open for questions now while you're gathering your thoughts. I'll satisfy my curiosity.

Terry Martin:

I mean, when you're talking about why it's been disregarded, I mean, you should give yourself some compliment there too in the sense that I would have liked when I wrote my book to have said something interesting about Kazakhstan, the famine, and nationality's policy. But it's simply very difficult to do from Moscow.

Terry Martin:

You know, in the area where I found documentation for other questions, there wasn't much Kazakh famine at all. Now I was early and the archives weren't open yet, so I couldn't ... I made inquiries. Couldn't go to Kazakhstan. But I think you've done a great job of finding stuff that wasn't self-evident. It's much easier to write about the Ukrainian famine, or was.

Terry Martin:

Two things that I, in my own research, this is to satisfy my curiosity. The one thing that wasn't hard to find information about in Moscow about Kazakhstan was ethnic conflict in the 1920s. The perception, you know, and this is all coming from Russophone sources, so I'm also curious whether you think this is correct. But the perception in Moscow was that ethnic conflict in Kazakhstan was the worst in the country by a considerable degree.

Sarah Cameron:

The worst in the Soviet Union, yeah.

Terry Martin:

In the Soviet Union, yeah. And so I was always a bit curious about whether that might have had some impact on causation of the Kazakh famine. So I'd be curious whether you think that that observation is in fact accurate, because it's very clear to me that the voices are all Russian.

Terry Martin:

And the second thing was Goloshchyokin has this odd ... I mean, he has an odd tenure from the Soviet East, and the Soviet East in the 1920s, it was extremely hard to run a republic. And virtually every republic first party secretary fails, and they're being removed multiple times, both indigenous and Russian. And it happens in Kazakhstan until 1920s, and basically the typical pattern is that they're all removed until 1928, and then when Russia ... when Stalin backs him with force, they're able to establish rule and they tend to rule through ... except '38, when they get killed.

Terry Martin:

So Goloshchyokin is odd in that he's able to establish adequate control over the republic, at least not to be removed, and then he's removed in '33, which [inaudible 00:40:39] muddled, you know. So I was also curious whether there was anything distinctive about Goloshchyokin that plays in a role in the famine. Was he an unusually hard man? Was he an unusually successful at coercion that he was able to run a very difficult republic successfully, is my-

Sarah Cameron:

So is your question why did he stick around ... why was he kept around for as long as he was? Is that, yeah?

Terry Martin:

Yeah. Why was he successfully able to run the republic? From the perspective of Moscow. I'm not saying successful, obviously, from the perspective of Kazakhs. That early, and did that ability have anything to do with the famine? To [inaudible 00:41:28] the questions.

Sarah Cameron:

Yeah, yeah, yeah, no, no, no. The question of Goloshchyokin is a tricky one. I think, actually, we really need ... to answer that question conclusively, we really need something like what your student, [Marcia Blackwood 00:41:42], has been working on, right? We need to understand ... so she's been looking at a lot of the Kazakh communists in this period, and we need to understand their relationships to Goloshchyokin a little bit better.

Sarah Cameron:

I started to look at some of that stuff myself, but it's actually an immensely complicated story. It's really, really complicated.

Sarah Cameron:

I mean, I do know that ... and I wish I had more sources on Goloshchyokin himself. That's one of the problems in trying to bring out this side of this story. I mean, my sense is that he was sent in to fix a problem, which was to bring this republic more under Moscow's control. I have a sense that he was a pragmatic administrator, right, he tried to sort of kind of soften the consequences sometimes of the party's actions when they didn't go the way that they wanted.

Sarah Cameron:

But that he was also someone who didn't have a very good understanding of Kazakh society. He very rarely traveled out into the region. So I don't know if I ... I think really, to answer this question, we need a better study of his interactions with the party elite, of the Kazakh party elite during this period. There are a lot of unanswered questions in the history of Central Asia.

Terry Martin:

Yeah, for sure.

Sarah Cameron:

And with the issue of ethnic conflict during the famine, well, it does-

Terry Martin:

I am conscious of ... I should say that the sources I have are 1919 to 1927, when I'm talking about it, the salience of it, sorry.

Sarah Cameron:

Yeah, I guess I don't mean to ... certainly ethnic conflict played a role during the famine. You can see that clearly coming out in the sources. At the time that I was writing the book, I was also struck by something that I didn't see talked about as much, which was the Kazakh-Kazakh conflict, right. That was a perspective that I felt was sort of missing from the literature, in part mostly because I think a lot of the studies that we have of violence during this period are telling the story from Moscow's perspective, and then the assumption becomes who was actually doing this. Oh, well, this was Russians, or this was outsiders, right.

Sarah Cameron:

But certainly it played a role. However, if you look at where non-Kazakhs lived in Kazakhstan, they didn't live all over, right. They were only in distinct regions of Kazakhstan, so it's only part of the story, I would say.

Sarah Cameron:

And going back, also, to the first point that you made about the difficulty of writing about this famine, the Kazakh famine in particular, I think I have benefited from, in part, from some of the fabulous document collections that have come out recently. That's probably something that's changed since you were writing your book, so there's the Tragedy of the Soviet Village, right, this amazing document collection that Lynne Viola and others have worked on.

Sarah Cameron:

The Kazakh government, oddly enough, for historians of the Kazakh famine, the Kazakh famine is not something that they really want to touch. A lot of people told me, "Ooh, ooh, not a lot of government support for working on that topic." But at the same time they've actually produced some really amazing document collections.

Sarah Cameron:

There's two volumes out now of a document collection on the Kazakh famine called the Tragedy of the Kazakh Awul. It is an amazing document collection. Each one of these volumes is about 800 pages. Of course the first volume came out after I had finished my research so I thought, ah, you know. Why couldn't I have had this before I researched the book? But it still was really, really helpful to me, actually, in clarifying some of my thoughts and of course tracing down a few documents that I didn't get in the archive.

Sarah Cameron:

So I think actually the story just using published sources alone, you can actually do a ton more really amazing work on the Kazakh famine, given some of the things that have come out in recent years.

Terry Martin:

Okay. Questions. Mark?

Mark:

I have a couple of quick questions. [inaudible 00:46:15] would be other scholars have looked at this, like [Mikolov 00:46:18] and [Cholov 00:46:19].

Terry Martin:

Yeah.

Mark:

Whose work you cite in your ... I'm wondering, how do you see your book fitting into what they have done, and I'm thinking in particular of his book, but also of the others that you cite there.

Mark:

The second question would be in using the term nation-building, I'm wondering whether that ascribes too much purposiveness to it. That is, if it was the consequence, but whether that was the design, I think is questionable, that even with the ethno-territorial demarcation, it wasn't ... it's not clear to me that the intent was to build nations. That was the consequence, but I'm wondering what you see, was that goal there specifically at Kazakhstan from the outset?

Mark:

And then the final quick point that I want you to address, which goes to the meddling question. In the case of independent Ukraine, the issue wasn't raised either until Yushchenko's government came alone, except by the diaspora which of course it had been raised going back to the 1970s and 1980s when the Congressional resolution was passed, I think, in 1983 or something, year, at the behest of Canadian and the US Ukrainian diaspora. So why haven't ... and it then became even more active after Ukraine became independent, and then Yushchenko's government picked up on it very actively.

Mark:

So why ... I mean, I realize the Kazakh diaspora is much smaller, but there is some. Why haven't they tried to be more assertive on this issue?

Sarah Cameron:

So to your first question, there are a number of other scholars who work on the Kazakh famine, Western scholars, many excellent Kazakhstani scholars, of the famine. A lot of them, as I mentioned, this is not a topic that the current Kazakhstan government looks very favorably on, so many of these Kazakhstani scholars of the famine are of an older generation. They were writing about it right around the Soviet collapse.

Sarah Cameron:

But with regards to Western scholars of the famine, there's an Italian scholar, Niccolo Pianciola who you mentioned, the German scholar, Robert Kindler, and a French scholar, Isabelle Ohayon. And they do wonderful work. I've benefited enormously, actually, from their research, but I would say that we each have different perspectives.

Sarah Cameron:

So Pianciola, who you mentioned, he's an economic historian mostly I would say. Kindler is someone whose focus is, I would say, on violence. And Ohayon has done a kind of social history of the famine.

Sarah Cameron:

The lens that I have used to examine it is one of Soviet modernization and nation building, and I'm the only one of the group who has tried to integrate Kazakh sources, which I think are really pretty important to understanding a couple of things. One is the particular nature of this transformation of Kazakh society, what happens. And also to understanding some of the debates in Kazakhstan today about the famine, because there's, you know, I've had Kazakh scholars tell me, "Oh, look, I could publish this book in Russian. I'm going to publish it in Kazakh because this is a Kazakh problem and I'm speaking to a specific Kazakh audience." So I think to really understand the historiography and the local scholarship, you have to have that as well.

Sarah Cameron:

But certainly this is a topic that needs many more books on it. There's a lot unanswered questions about the Kazakh famine.

Sarah Cameron:

With regards to the Kazakh diaspora, I don't ... you know, I don't know. I guess I would point back to some of the same answers. Some of the same answers, I would say, about why the famine is not talked about in Kazakhstan today. It's maybe Kazakhstan's close relationship with Russia, this belief that, you know as I've had some Kazakhs tell me, for instance, that well, Soviet rule, that had some positive benefits as well. You know, we were nomads before, and now we're a modern society, right. So there's this kind of maybe ambivalence about the Soviet past that's sort of still kind of lingering to a certain extent.

Sarah Cameron:

The Kazakh diaspora perhaps is not as unified. It's more dispersed than the Ukrainian one. They have not, to the same extent, for instance, I am not aware of any centers for Kazakh studies. You know, how many centers are there for Ukrainian studies? So if you just follow, for instance, if you follow the money trail for Kazakh studies, it's not there.

Sarah Cameron:

So with regards to the question about nation-building, well, when I use the term in the book, I use it in quotation marks. But I do believe, actually, that this was something that they took very seriously, and that this was a goal. And this is something that's actually one of the sort of arguments of the book, is that I think actually this nationality policy, which was the sort of ... if you say the word policy, sometimes that makes you think that it was actually written down in a book, like there was a blueprint, but no, it was this kind of working set of ideas and assumptions that guided Moscow's thinking about and local thinking on the ground about how to transform people, and I think actually it was something really crucially important. And so that's one of the major arguments I'm trying to to make is that I think that's really important to understanding the Soviet project.

Terry Martin:

Great. Well thank you, Sarah, very much.