Demography plays a starring role in Russia’s dreams and nightmares. Meeting with schoolchildren in Vladivostok on Sept. 1, Russian President Vladimir Putin asserted that had it not been for the October revolution of 1917 and the collapse of the Soviet Union, “some specialists believe that our population would be over 500 million people. Imagine that.”

As it stands, the state statistical service reported that in 2020, Russia experienced the largest drop in its population since 2005, driven largely by COVID-19 deaths. To make matters worse, analysis by the Center for Eastern Studies in Warsaw found that the birthrate reached a 20-year low and emigration exceeded migration. In a CNBC interview on Oct. 14, Putin emphasized that increasing the number of citizens is one of the government’s most important priorities: “[T]hese two main problems—demographics and increasing income levels, improvement of the quality of life… This is what we plan to work on in the near term.”

Russia’s population peaked in 1992 at 148.5 million and has slowly drifted downward ever since, with World Bank data suggesting the population currently stands at 144.1 million. This is often put forth as part of the evidence that Russia is a country in decline. (The other significant evidence being the decline in Russia’s share of global GDP.) Nicholas Eberstadt, a leading demographer, once titled an article “With Great Demographics Comes Great Power,” with the converse also clearly implied. There’s little doubt that Russian demographic trends look discouraging. But should this change the U.S. approach to the country? No. The possibility that Russia might have fewer people and a smaller economy will not negate the fact that it is a nuclear superpower with unfriendly intent. What Russia becomes is less important than what Russia is willing to do.

Demographic Trends

The coronavirus pandemic has hit Russia very hard. Only about a third of the population has been fully vaccinated with the Sputnik vaccine; mistrust of the government in general and the vaccine in particular suggest that jab rates will not rise quickly on their own. Putin may not want to risk imposing extensive vaccine mandates if they are likely to be ignored and make him look weak. COVID infections peaked in late October, and the country has reached the discouraging watershed of having lost over half a million people to the virus, according to official statistics. Excess deaths year on year since the start of the pandemic suggest the actual number could be at least 50% higher, according to the Financial Times, among others. This is in part due to the higher COVID-19 mortality rate in Russia compared to the global average of 2.2%, according to estimates by Johns Hopkins University.

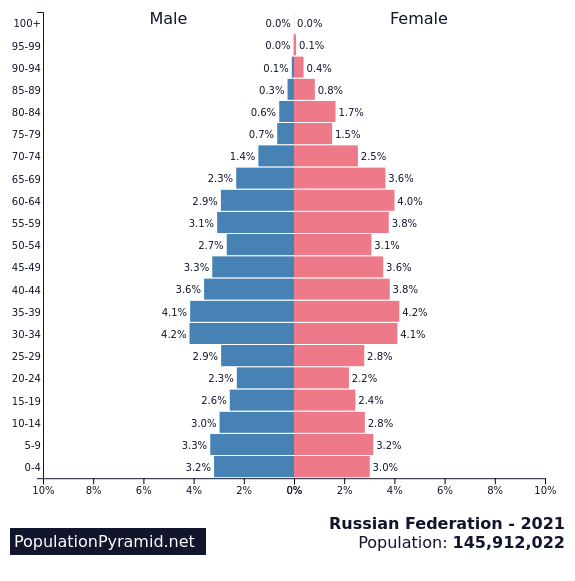

The population loss from COVID comes on top of already unfavorable demographic trends. Populations can be represented by age-sex pyramids that capture the number of people of each age at any given time. Countries with high birthrates have age-sex pyramids that look like triangles with a wide base of newborns. Countries with aging populations have pyramids that look more like unbalanced trees, with a wider band of older people dwarfing the smaller number of younger people. In Russia, the age-sex pyramid looks like an unstable Christmas tree. The indentations every 20-25 years represent the long-term cyclical impact of the country having lost so many people in World War II. Each subsequent recovery is narrower, suggesting that the number of fertile women in each generation is getting smaller and smaller. That doesn’t bode well for the birth rate.

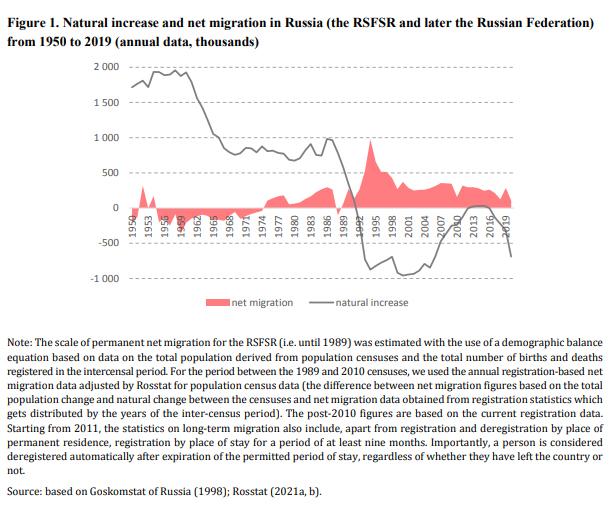

The government is of course aware of this problem and has for years pursued pro-natalist policies to boost the birth rate. The Maternity Capital program, for example, was introduced in 2007 to encourage women to have a second or third child. The entitlement, now worth about $6,500, can be used to upgrade housing, for education or to fund the mother’s pension. Some Russian demographers attribute the rise in the birthrate between 2013 and 2015 to this program. Data reveals that births in Russia peaked in 2014 at 1.95 million and have fallen to 1.44 million in 2019.

The only positive demographic trend for Russia had been increasing life expectancy, but that trend was reversed by COVID-2019. In 1994, male life expectancy had dropped to 57.7 years, but was up to 68.2 in 2019. Russian women, who tend to live at least a decade longer than men, had a life expectancy of 71.2 years in 1994. Now, on average, women can expect to live to 78.2, according to World Bank indicators. In contrast, overall life expectancy rates in the U.S. are about five years longer.

Countries with unfavorable demographic trends often turn to migration to supplement their populations, and Russia is no exception. Official statistics reflect only registered migrants—not those in the country off the books. Russia has a positive migration balance every year, as more people move into the country (usually) from former Soviet republics than move out to other parts of the world.

A recent study by Florinskaya and Mkrtchyan based on data from the first months of 2021 revealed that only 14.6% of the population losses due to COVID were being covered by so-called long term migration from former Soviet republics. This is a problem for the countries that rely on migrant worker travel to reduce domestic unemployment and provide remittances to boost GDP, as well as for Russia, which relies on the cheap labor, particularly in agriculture and construction. In April, presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov said, “We have had very few migrants remaining over the past year. And we really really need these migrants to implement our ambitious plans… We must build more than we are building now. We need to build significantly more. But that requires hands. Their number has dropped due to the pandemic.” Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Marat Khusnullin has estimated that Russia will need to attract at least 5 million construction workers from abroad by 2024 to meet government building targets.

Implications for Foreign Policy

How do these demographic trends tie into Russian foreign policy? Most directly, Russia wants to increase the number of Russian citizens. If it cannot produce them biologically, it will need to acquire them through other means. A 2002 lawmade it relatively simple for former citizens of the Soviet Union to claim Russian citizenship. An updated 2020 version of the law makes it even easier to become a Russian; applicants need no longer prove they have a legal source of income, and former citizens of the Soviet Union can now apply for Russian citizenship without proving residency. Citizens of Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan who have a Russian residency permit no longer have to wait for three years before applying for citizenship. Russia has also been aggressive about “passportizing,” or offering Russian passports to residents of contested territories in Georgia (Abkhazia and South Ossetia), Moldova (Transdnistria) and Eastern Ukraine. Besides limiting the ability of the national governments to administer their territory, this policy has created at least another 1 million Russian citizensThe 1 million figure is calculated based on the following: according to the Polish think tank The Warsaw Institute, as of 2008, 90% of the population of South Ossetia (or some 48,000 people) and 85% of Abkhazians (208,000 people) had Russian citizenship, and 250,000 out of 500,000 people living in Transnistria hold Russian citizenship. The institute also estimated that as of May 2021, 530,000 Ukrainian residents of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions had been given Russian passports. In addition, The Guardian estimated in May 2021 that 650,000 Russian passports had been distributed in Eastern Ukraine. while also giving Russia a pretext for being involved in the politics of these countries under the guise of protecting Russian citizens. The most extreme version of seizing another country’s citizens was the annexation of Crimea, which added another 2.5 million citizens to Russia’s population.

When it can’t acquire citizens, Russia looks for Russian-speaking supporters abroad who see benefits in being closely associated with Russia. Russia has pursued a “compatriot policy” of ostensibly supporting the interests of Russian citizens—or sometimes just Russian speakers—abroad in the Baltics since the late 1990s. In Estonia and Latvia roughly a quarter of the population is ethnic Russian (in Lithuania this number is closer to 4.5%). In 2007, the Russian government founded and funded the Russkie Mir organization to promote the consolidation of a “Russian world” abroad, though it has admitted to being most successful in the developing countries of Asia, Africa and the Middle East. There, the organization focuses on supporting Russian language programs, which may not have a discernable effect on foreign policy.

And when it can’t rely on supporters, Russia will use laborers. Russia’s employment of Central Asian migrant labor provides it with a means of exerting influence—and pressure—on the five countries to its south. The Central Bank of Russia estimated in 2021 that monthly remittances from migrants to Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries average around $500 million, and reached $720 million in June. The FT calculates that these remittances can be as high as 30% of a CIS country’s GDP, and are one way they have mitigated the economic impact of the coronavirus. These countries can ill afford to alienate Russia and risk having their laborers expelled and sent home, though Russian scholars note that they all try to pursue “multivector” policies that balance their dependence on Russia and China.

The impact of unfavorable demographic trends on Russian foreign policy is important in that it affects how it relates to its neighbors in former Soviet republics. Russia wants to attract Central Asian laborers to work on infrastructure and agriculture. Ideally some of these migrants would work in Siberia and the Far East, where the population has been dwindling. The possibility of extending Russian citizenship to populations in disputed territories is attractive not only for demographic reasons, but also because it allows Russia to continue playing the spoiler in Georgian, Ukrainian and Moldovan politics, which in turn weakens national cohesion and makes these countries less attractive to Western institutions they might like to join.

Rosstat’s pre-pandemic forecasts assumed that only increased migration could offset a natural demographic decline of 3-8% by 2036. And Russia’s economy may be the 6th largest in the world, but it represents just over 3% of global GDP (by PPP) compared to China’s 18% and the U.S.’s 16%, according to latest IMF data. Yet the shrinking of Russia’s population and a stagnating economy should not be driving American strategy. Russia may or may not be a declining power, but it is not a declining threat, in the words of Michael Kofman. Russia will continue to interject itself in the global order in ways that undermine our principles and goals. Its military will remain a force to be reckoned with, its cyber-capability will continue to improve and its willingness to foment agitation abroad will not diminish. We cannot afford to dismiss Russia as a declining power and focus on China. We must deal with Russia as it is today, and not as it might end up generations from now.

This piece was originally published on December 21, 2021, by Russia Matters: https://russiamatters.org/analysis/russias-discouraging-demographics-shouldnt-change-us-approach