Full video of Guriev’s talk is available on the Davis Center’s YouTube channel.

Economist Sergei Guriev believes that understanding Russia’s economy — which went in 20 years from growth to stagnation but has proved surprisingly resilient under Western sanctions — greatly helps to understand Vladimir Putin’s popularity and the durability of his regime. Looking ahead, the connection between economics and politics gives Guriev hope that whoever comes to the helm in Moscow after Putin will have no choice but to liberalize the state’s policies, at least a little, and to seek rapprochement with the West. Before then, however, the Sciences Po provost and former chief economist of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development believes that Western sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine need to be ratcheted up — not simply to signal support for Kyiv but because we have reached a “very depressing moment” when existing measures are not sufficient.

A Brief Economic History of Putin’s Russia

Guriev kicked off his keynote address at the Davis Center’s recent 75th anniversary event with a brief economic history of Putin’s Russia, going from growth to “Putinomics” to stagnation:

- Its first 10 years (1999-2008) marked one of the Russian economy’s best decades, “if not the best,” on record; a weak ruble made the country more competitive, unused production capacity created business opportunities, and rising oil prices accounted for about half of Russia’s GDP growth, which averaged 7% a year. The economy was likewise helped along by reforms that stimulated private-sector initiative — a simplified tax system, property rights for land, and modern bank regulation, among others.

- Then came the global economic crisis of 2008-2009, throwing into relief problems that had begun to accumulate earlier. Circa 2003-2004, Putin, rather than pushing through more reforms, had started introducing “Putinomics” — an economy increasingly “controlled by the state and friends of Putin,” Guriev said. Despite an initial recovery after the crisis, it was clear that “the growth model of Putin’s first decade was running out of steam,” in Guriev’s words; growth in 2010-2012 began slowing down, reaching a paltry 1% in 2013.

- Afterward, Russia’s economy entered an era of stagnation, akin to the 1970s and ’80s, with GDP growth in 2013-2019 averaging less than 1% a year. Unlike South Korea — which once had a growth trajectory similar to Russia’s halcyon years — Moscow failed to dismantle its system of crony capitalism. Today, Seoul presides over a competitive, post-industrial, knowledge-based economy, Guriev noted, while Russia got stuck in the so-called middle-income trap.

Regime Legitimacy and Spin Dictatorship

Putin’s first 20 years in power, combining economic successes with macroeconomic and political stability, saw him and his team build what Guriev calls a “spin dictatorship,” a phenomenon he explores in a new book with coauthor Daniel Treisman. The idea at the book’s heart is simple: Instead of scaring people into obedience, most modern autocrats manipulate information to project an image of competent leadership and to convince their subjects that any alternative would be much worse. Today’s dictators wear business suits instead of military uniforms, glad-hand with democratic leaders, and use sophisticated toolkits to repress and censor in deniable ways. Putin was not a pioneer of this approach but proved to be one of the best at it, Guriev argues.

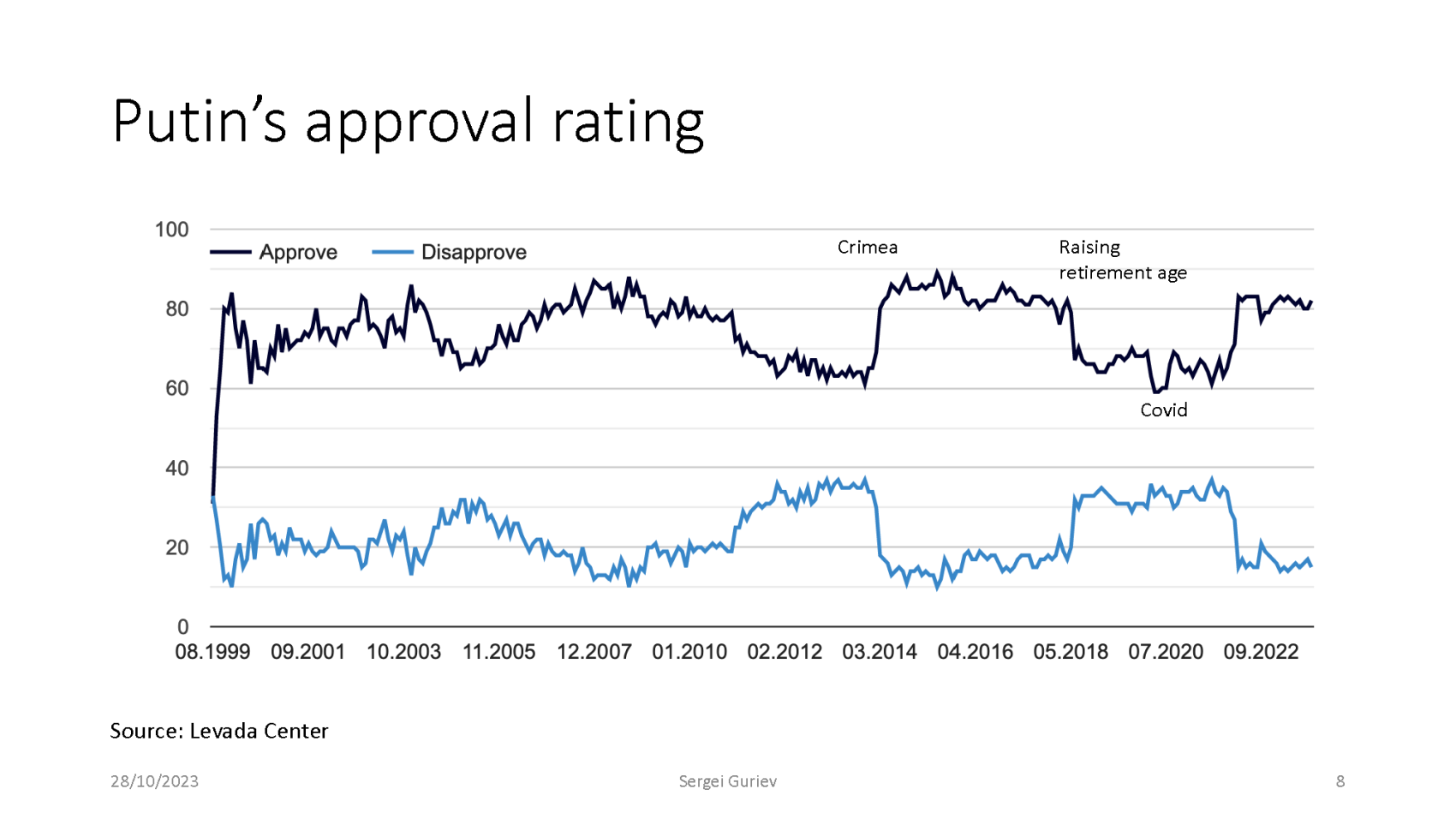

One measure of spin’s success is popularity, which matters even in autocracies; in Putin’s case, drops in popularity may have fueled some of his policies, including the moves against Ukraine in 2014 and 2022. On the chart below, as Guriev pointed out, we can see that both the annexation of Crimea and last year’s full-blown invasion came at a time when Putin’s approval rating had dipped sharply and stayed low for several years (though still around 60%).* The Crimea grab, with its imperial “great Russia” narrative, boosted Putin’s rating for a time. But, with no new sources of economic growth and an outdated Kremlin media strategy that initially failed to control social media, Russians’ sense of regime legitimacy post-2014 began to fade. After an unpopular move by Putin to raise the retirement age and the poor handling of COVID-19, the president’s approval rating plummeted once more — until 2022.

From Spin to Fear

As Russia began its 2022 war against Ukraine, Guriev believes, Putin's regime accelerated its transition from spin dictatorship to full-on fear dictatorship. The main transformation, he said, happened “in the first week of the war,” when “Putin saw that his plan to replay 2014 quickly” — without extreme brutality or major economic consequences — was not working. Newly harsh measures to punish dissent were introduced hand in hand with stricter censorship, including the blocking of Facebook and Instagram, which had long helped Russians circumvent preexisting media restrictions. (Earlier research by Guriev and Treisman has shown that censorship had contributed quantifiably to Putin's popularity.) In short, Russia’s political system has become far more openly repressive, with the number of political prisoners “much higher than it used to be” and “already comparable” to the late Soviet period, by Guriev’s estimates.

Some of these repressive trends had been apparent earlier. One litmus test of change was the treatment of opposition activist Alexei Navalny, who, as recently as 2021, used to reach millions of people every week via YouTube with his exposés of high-level corruption, challenging official propaganda and vexing the Kremlin. Initial attempts to silence Navalny, beginning about a decade ago, revolved around charges like embezzlement — “a typical spin dictatorship tactic,” said Guriev, whereby political opponents are labeled “crooks” and regimes can bat away accusations of political repression. In August 2020, as Putin’s popularity took another hit amid the pandemic, Navalny was poisoned; Putin, still in spin dictator mode, denied any involvement by the state, taking credit instead for allowing Navalny to get treatment abroad. Once Navalny boldly returned to Russia in January 2021, he was jailed and later convicted — not for economic crimes but on graver charges of extremism.

Naturally, some elements of a spin dictatorship remain, Guriev noted, as Putin had been building up that system for 20 years and all transitions take time. There are still institutions and stakeholders in Russia who were essential to the spin dictatorship: seemingly competitive elections and the officials who run them, other officials who oversee domestic politics within the presidential administration, nominally oppositional political parties, and the like.

Impact of Sanctions

Time and time again, ever since the U.S., Europe, and their allies introduced sanctions in response to Moscow’s military intervention in Ukraine in 2014, the Russian economy has proved far more resilient than many experts expected. Despite new challenges, including formidable ones for the longer-term future, Russia’s GDP by late 2023 had bounced back to pre-war levels. Two reasons for the mismatch between predictions and reality, Guriev said, are the delayed imposition of oil sanctions and the fact that few people realized how quickly competent policymakers in a repressive state can restore macroeconomic stability.

Putin’s attempts to build up “macroeconomic Fortress Russia,” as noted before, predated the war, but they weren’t necessarily made in preparation for war, Guriev pointed out. Instead, they fit into the Russian leader’s idea that his country must be strategically independent, without needing “to call [the] IMF and ask for permission to do something.” Hence, Putin’s policymakers prioritized a textbook version of macroeconomic stability: low debt, high currency reserves, a large sovereign wealth fund. In part for this reason, the impact of the 2014-2021 sanctions on Russian GDP “was not zero, but it was very, very small,” Guriev said.

The punitive measures initiated in 2022 were “a completely different set of tools,” leaving Russia with “more sanctions imposed on its economy than all other countries in the world combined,” according to Guriev. Yet, despite unprecedented moves like the freezing of $300 billion in Russian central bank assets, Russian coffers continued to fill up. This was due largely to high oil prices and continuing energy sales to Europe, which did not introduce oil sanctions until December of last year. Thus, 10 months after its all-out attack on Ukraine, Moscow closed out 2022 with a $230 billion trade surplus.

This is not to say that oil sanctions, once Europe’s came into effect, had no impact on Putin’s ability to finance Russia’s war against Ukraine. They affected the ruble, inflation, and, in particular, the Russian budget for the first half of 2023, when oil and gas revenues “came down by half year on year.” Circumventing the sanctions is also costly, requiring layers of intermediaries and additional expenses, like Russia’s reported fleet of environmentally dangerous “shadow tankers.”

Today, however, Russia is not running a budget deficit and Guriev believes Putin will be able to keep funding his military machine if oil sanctions aren’t tightened. Guriev noted that in the third quarter of 2023 Russia started selling oil at prices above a Western-imposed cap and the country’s planned 2024 budget “is really scary,” boosting military spending to its post-Soviet high — an estimated 6% of GDP, which Guriev contrasted with NATO’s benchmark of 2% for its own members. Russia, with its combination of petrodollars and forex reserves (including yuan), will be able to ramp up its own production of weapons and munitions, while buying what it can’t make from suppliers like Iran and North Korea and continuing to pay for intermediaries that help it evade sanctions.

In the long run, Guriev says, Putin's economy is not great, plagued by capital outflow and lack of access to modern technologies, but Russia’s revitalized repressive apparatus can easily tamp down discontent for now. Rosy GDP figures are misleading during wartime, Guriev pointed out, because they reflect ramped-up military production, which doesn’t contribute either to quality of life or to future economic growth; some indicators, in fact, suggest a grimmer economic picture for ordinary Russians — for example, a 10% drop in consumer spending in 2022. But, ultimately, diminished quality of life becomes less of a political liability when the regime openly punishes its critics with years-long prison terms.

After Putin

Putin, of course, is mortal and the moment he leaves the Russian political scene, Guriev believes, “he will be succeeded by people around him.” Since no one from the small circle now close to the president is charismatic or popular enough to become a “Putin 2.0,” the new leadership is likely to be more collective than personalistic. Moreover, studies of non-democratic regimes suggest there will be some infighting; Guriev added that Putin has cultivated an arrangement where senior officials “hate each other and distrust each other,” so we may see “some defenestration, some strange deaths, some departures from Moscow to Venezuela or Africa.”

That said, after months or years, Guriev believes, we will again see in Russia “something like perestroika.” The logic behind this prediction comes back to the connection between economics and politics: Since none of the post-Putin contenders for the Kremlin have claims to legitimacy that are indisputably greater than their competitors’, whoever gets the upper hand will eventually realize that they can’t consolidate power further without some popular support. For that they will need a measure of economic success — the easiest path to which, of course, would be removing sanctions. “And for that,” Guriev points out, “they will need to reach out to the West.”

The West, Guriev feels, should prepare for this moment. For Ukraine it should demand the withdrawal of Russian troops, reestablishment of territorial integrity back to Ukraine’s 1991 borders, reparations, and an international tribunal for war criminals. And for Russia, while acknowledging that no outside force can impose democracy there, Guriev nonetheless believes that the West could incentivize political liberalization, including the release of political prisoners and opening up the political system for internal competition. “Why is that important?” he asked the audience, and answered: “Because … sustainable, durable peace in Europe and in Ukraine will only be possible when Russia is democratic.”

*While polling data coming out of any spin dictatorship must be taken with many grains of salt — a topic discussed at length in Guriev and Treisman’s book — respondents’ bias factor remains relatively steady, according to Guriev, so these data, before 2022 at any rate, are useful in showing change over time. Guriev did not imply that falling approval ratings were the only driver of Putin’s policies.