Russia’s attack on Ukraine has already begun to dramatically reshape the global order in ways few could have imagined just weeks ago. As much of the world, led by Europe and the U.S., has coalesced to sanction and isolate Russia, one major power has been conspicuously absent: China.

How China views the Ukraine invasion and whether the hostilities and the growing international condemnation resulting from them will affect China’s ties with Russia were the focus of a Harvard Kennedy School talk Thursday with Anthony Saich, director of the Ash Center and Daewoo Professor of International Affairs at HKS, and Alexandra Vacroux, executive director of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University.

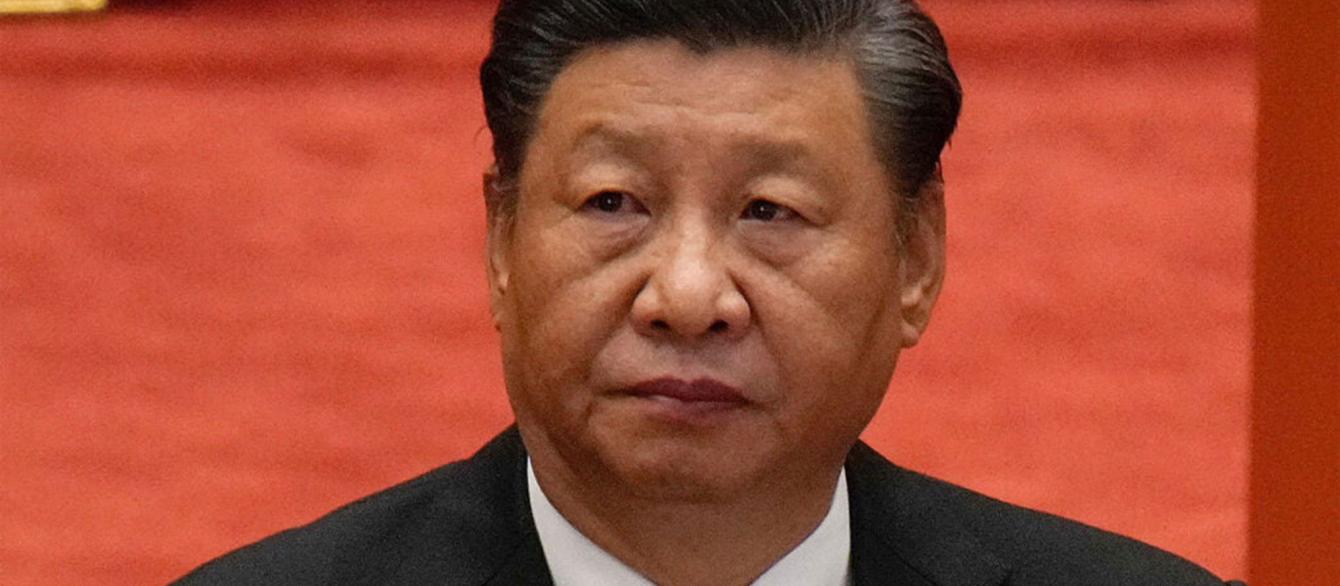

Vacroux asked Saich about reports that China knew in advance of Russia’s decision to attack Ukraine. China’s President Xi Jinping met with Putin, who attended the Beijing Games, on Feb. 4. The two countries then issued a joint statement criticizing NATO and pledged to work cooperatively against the West, in a partnership that had “no limits.”

Saich said while it’s still unclear whether China had advance warning of the Feb. 24 invasion, it “seems implausible” that it was never touched upon. While the two countries have a relationship, it is not an alliance so much as “transactional” partnership where China firmly maintains the upper hand.

“My suspicion is that probably Putin told [Xi] that he was going to move into the eastern parts of Ukraine, because of the threats against the Russian nationals and supporters there, and it would be quick, it would be clean, and it would be very quickly resolved,” he said.

That Russia did not deliver on that promise has “clearly” caught Chinese leadership by surprise and now makes the political tightrope China is trying to walk between Russia and the rest of the world “very difficult,” Saich added.

Ash Center Director Anthony Saich and Alexandra Vacroux, executive director of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, assess the ways Russia’s war on Ukraine could shape China’s ambitions for Taiwan.

China has twice abstained from joining a U.N. resolution, including a vote of the U.N. General Assembly this week, that condemned Russia’s actions and has resisted calls for sanctions, unlike neighboring Japan, South Korea, and Singapore.

By sitting out the global resistance to Putin, China runs the risk of being seen as too aligned with Moscow’s interests and feeling the sanctions backlash as a result, along with a deteriorating relationship with not only the U.S., but many other countries in Europe and beyond, said Saich.

But nonetheless China could ultimately decide to fully throw its support behind Russia’s actions. Key indicators that it had, Saich said, would include China vetoing U.N. resolutions, rather than merely abstaining from them; offering swift recognition to a puppet government in Ukraine should Putin install one at the end of hostilities; and continuing to refuse to call the Russian attack an invasion even when it is clear to the world that Ukrainian civilians are being killed and cities are being bombed by Russian forces.

As for the widespread worry that China is carefully studying Ukraine in preparation for a similar takeover of Taiwan, Saich said China doesn’t see the two as parallel issues and isn’t likely to be influenced by the outcome in Ukraine or the blistering global response to Russia. He predicted that China would not launch an action against Taiwan.

While China has lifted some trade restrictions on Russia and is expanding pipeline capabilities to bring more natural gas from Russia into the country in support of Putin, Russia’s exclusion from the SWIFT system for international banking has “shocked” Beijing leadership and may test that support, he said.

The invasion will take relations between the U.S. and China to “an even newer low,” said Saich.

China sees the Western opposition to Russia as just another example of U.S. aggression around the world, something that potentially threatens China’s rise. “The levels of mistrust between the U.S. and China now run very deep.”

“But Beijing also recognizes, as I think Washington should, that the two countries can’t do without one another. There are just too many global problems that need collaboration between the two powers, whatever Beijing might think of Washington, whatever Washington might think of Beijing,” he said. “So, I don’t think Beijing will want the relationship with Washington to deteriorate too far that it becomes impossible to salvage it.”

This article originally appeared in the Harvard Gazette on March 3, 2022.