Soon after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the Soviets took control of Central Asia, forming five new republics: Kazakhstan, Kirgizia, Turkmenia, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. The imposition of Soviet power proved highly disruptive to the traditional ways of life in these republics, which had been dominated for centuries by Muslim beliefs and practices. In the absence of an indigenous proletariat as the support base of the new regime, it was the region’s women—their activities and rights severely restricted by Sharia law and local tradition—who were chosen to play the role of the “surrogate proletariat.” The so-called emancipation of Central Asia’s women, whom Vladimir Lenin saw as the “most enslaved of the enslaved, most downtrodden of the downtrodden,” became a central pillar of the Soviet effort in the region.

The road to liberation that Central Asian women traveled proved to be a long and difficult one. They frequently encountered resistance from their communities and families. As elsewhere in the USSR, women’s new roles as professionals and builders of Communism did not fully supplant their traditional duties as daughters, wives, and mothers, forcing them to carry the double load of public and family obligations.

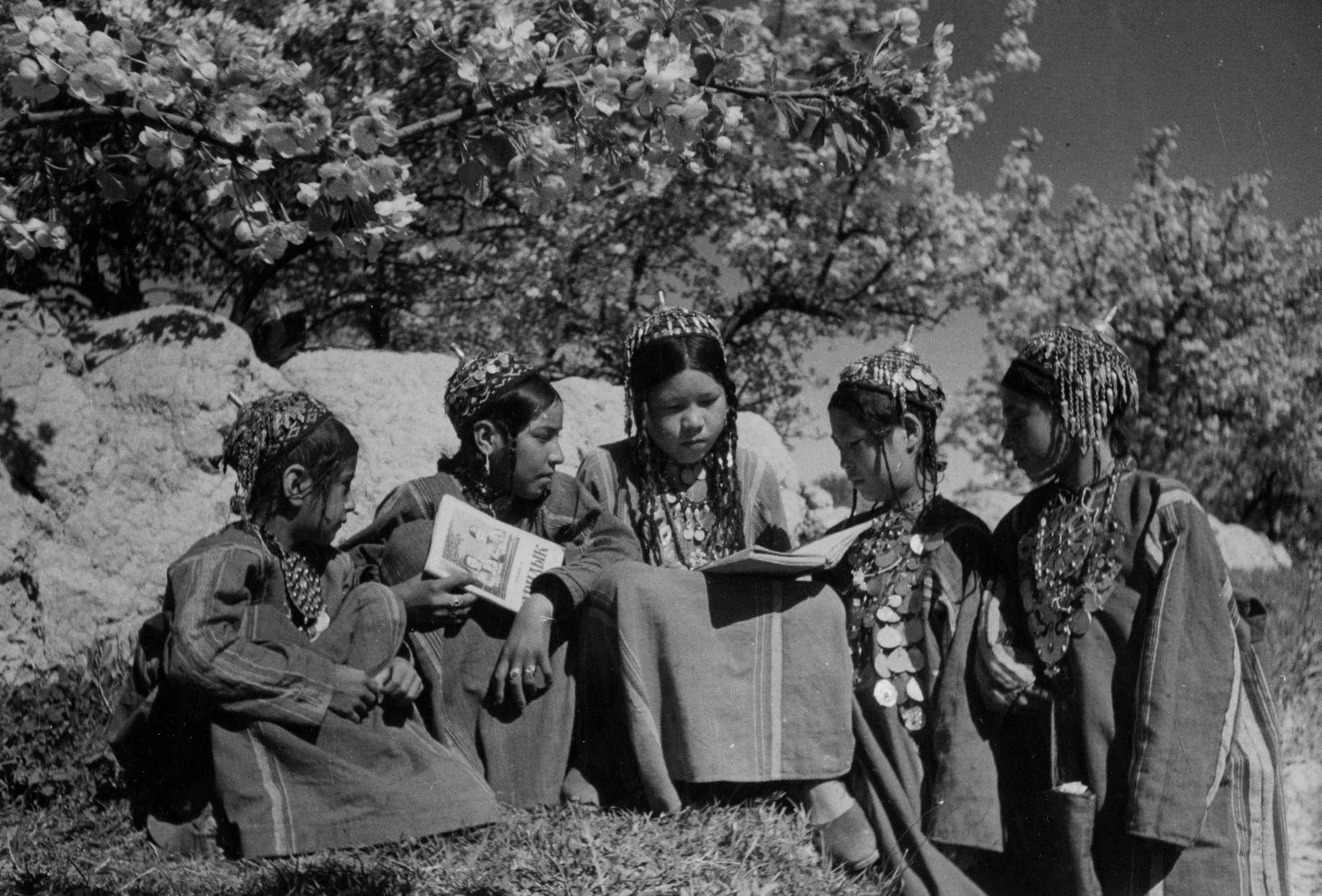

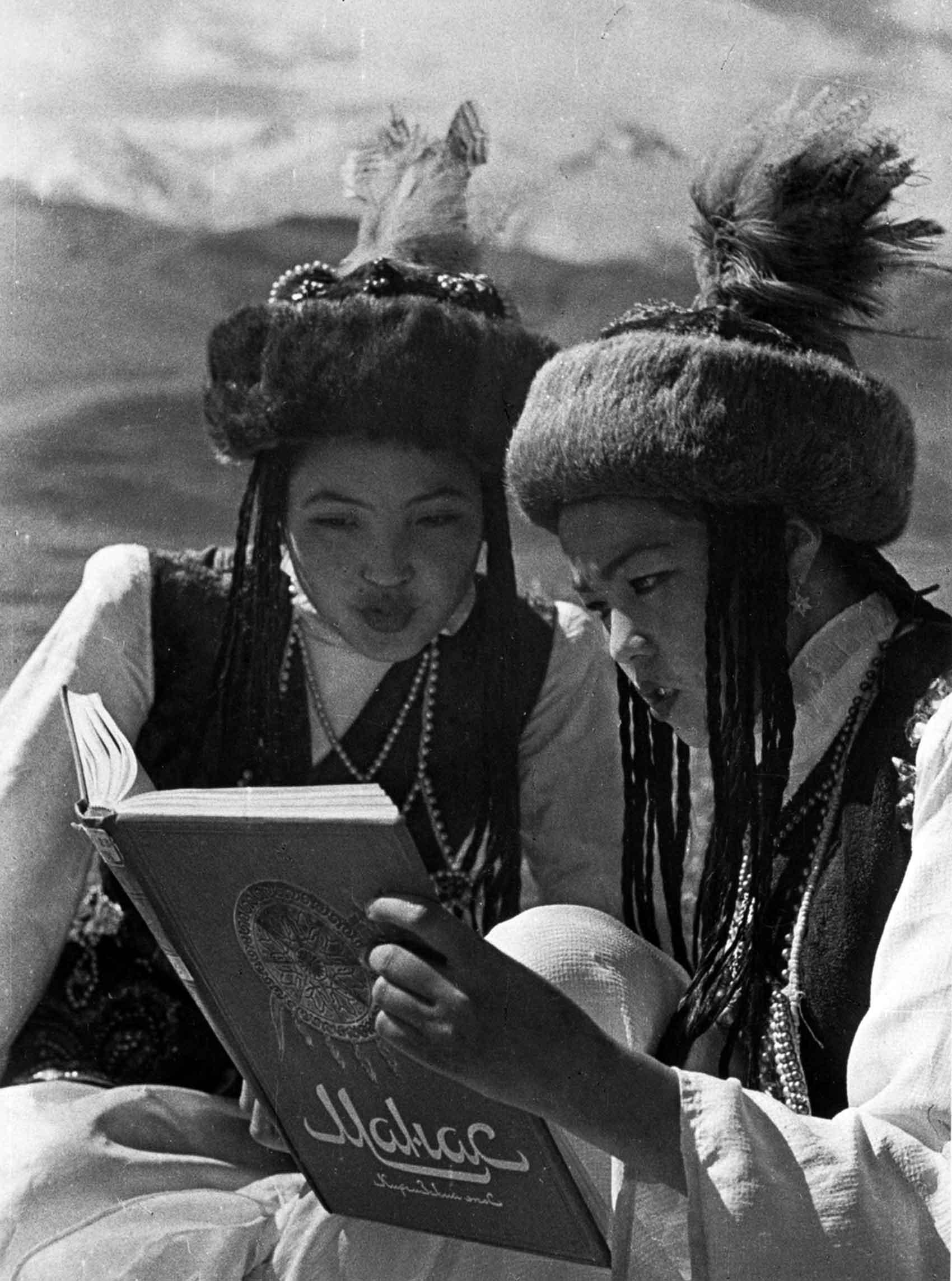

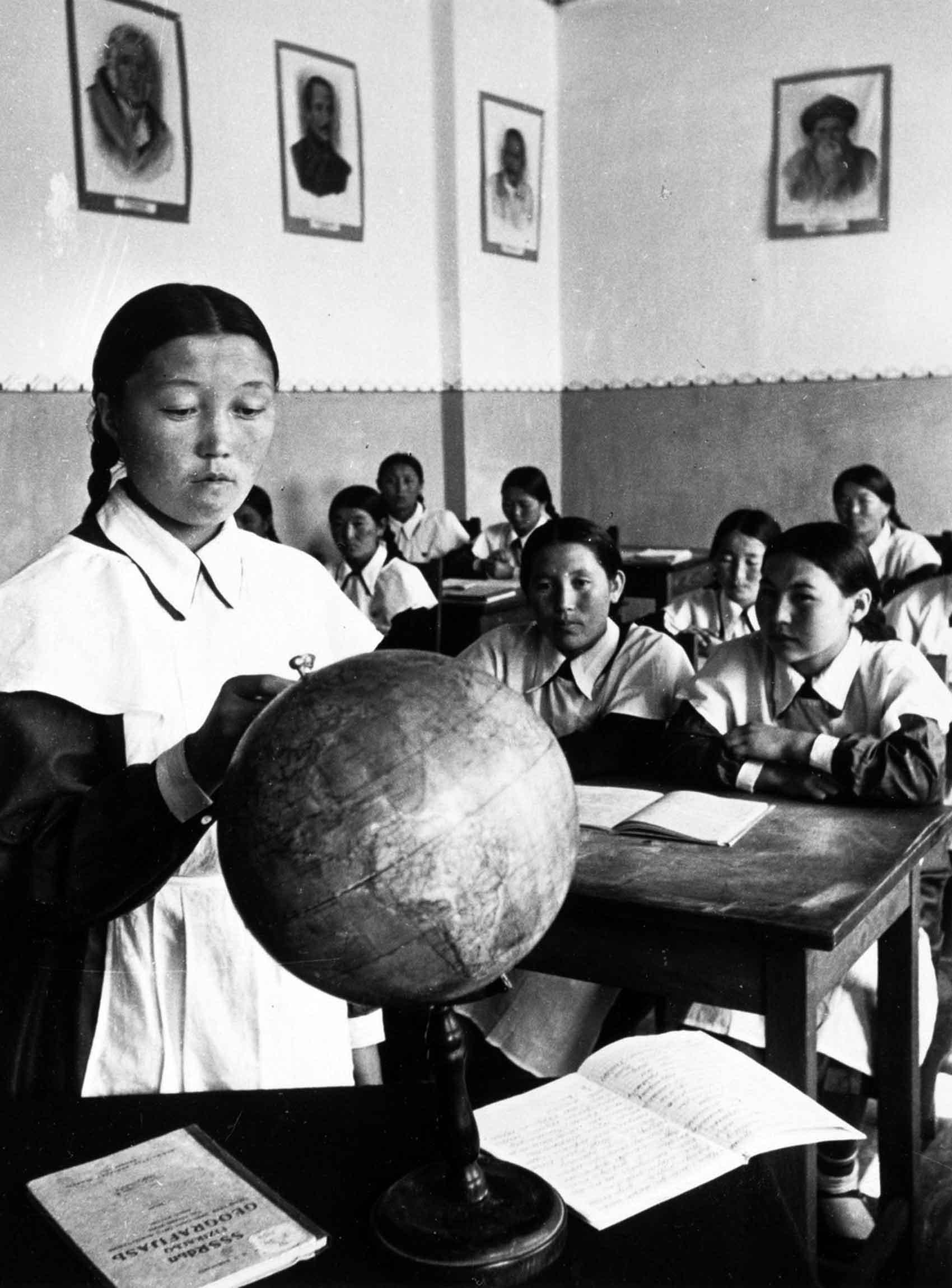

Still, the reforms promoted by the Soviets gradually took root. The propaganda photographs in this exhibit, taken in the late 1940s, show a radically transformed Central Asia. Though artificially upbeat, sometimes obviously staged, and often disguising the harsh realities of collectivization, these photographs nonetheless capture a mood of genuine buoyancy. The “liberated,” successful women and girls seen here are real. So are the optimism and self-respect they radiate in the face of newfound equality and opportunities.

Early Reforms; Removing the Veil

First came the adoption of legislation protecting the rights of women, and making them equal with those of men in all spheres of political, economic, and cultural life. In 1921 the government of Turkmenia issued a decree that set the minimum marriage age for women to 16—up from the 9 dictated by Sharia law. It also banned polygamy, forced marriage, and kalým (the custom of paying for a bride). The new norms were to be promoted among the public by Women’s Departments (Zhenotdély), created as part of regional and city committees of the Communist Party after 1919. Zhenotdél activists were in charge of organizing women’s literacy schools, orphanages, kindergartens, and childrearing consultations.

On 8 March 1927, activists in Tashkent celebrated International Women’s Day by launching hujúm—an assault on old ways and traditions that sought to more deeply transform everyday life and relations between the sexes. One of hujúm’s main goals was to eliminate the paranjá (head-to-toe veil) worn by urban Muslim women and girls in the presence of male nonrelatives.

The program was to be completed in less than six months, in time to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. Instead, it took three decades and another major upheaval—World War II—for a widespread “unveiling” and “liberation” of Central Asian women to take root.

During the interim, women found themselves facing pressure from two sides: the Soviet authorities, on the one hand, and society—most importantly their families and neighbors—on the other. At home, they risked being abused, divorced, and even killed for exercising their new rights. Outside, they could be treated as prostitutes. During the first years of the hujúm, thousands of Central Asian women were attacked and raped, and hundreds were killed, often by their male relatives. It is not surprising that many women who first publicly burned their paranjá would then quietly reveil completely, substitute the veil with a shawl, or veil and unveil depending on where they were. Social propaganda campaigns to end veiling, kalým, and other oppressive practices in the region continued into the 1970s.

Education

In 1930, the Soviet government launched a campaign for universal, compulsory primary education. Within a decade, school enrollment in the Soviet Union had tripled, with approximately one-third of enrolled pupils studying on the territories of the non-Russian republics. This surge required a major initiative to recruit and train teachers locally. Overall, the number of teachers in the Soviet Union increased from less than 400,000 in 1928 to over one million by 1939. Women were of crucial importance in filling this niche. Teaching would become predominantly a women’s profession all over the USSR, not least in Central Asia.

Girls in traditional clothing reading together.

Kirghiz girls reading the national epic "Manas"

Students at the Frunze Pedagogical Institute in the Republic of Kirgiziia. Training to become a teacher took 7 years.

Female instructor with students at Frunze Pedagogical Institute in Kirgiziia.

Entering the Public Sphere

Soviet emancipation policies allowed and indeed pressured women to take part in the industrialized economy. They became factory workers, tractor drivers, and heads of collective brigades and farms. Others became members of local and all-Union elected councils. Institutions of higher learning opened in Central Asia’s capital cities, and their women graduates often pursued scientific careers. In Soviet public discourse, Central Asian women were at once treated as a symbol of female liberation and fetishized, paradoxically, for their “exotic” beauty.

Postgraduate researcher at the Frunze Medical Institute, Republic of Kirgiziia.

Surakan Kainazarova, record sugar beet grower, elected to the Supreme Council of the Kirgiz Republic.

The Arts

Under Soviet rule, Central Asian artistic traditions were merged with the requirements of Soviet art—“national in form, socialist in content.” In addition to encouraging the preservation of traditional arts and crafts, such as copper engraving and carpet weaving, the Soviets—in what many today would see as an act of cultural imperialism—imported and fostered Western-style art forms. Plays by Russian and Western authors were staged. Conservatories opened and began training classical musicians. Some Central Asian women became artists, actresses, musicians, and dancers. Daughters of recently unveiled mothers were performing traditional dances previously reserved for men, while others mastered such Western forms of art as ballet and theater.

The Youth: "Socialist Socializing"

Such daring breaks with tradition were possible in large part due to the vigorous and comprehensive molding of youth carried out by the Soviet school system. All over the USSR, young people attended similar-looking kindergartens and schools, following the same curricula and using identical textbooks in Russian and national languages. Elementary school pupils all were inducted into the Little Octobrists youth group (named for the Great October Revolution), third-graders became Young Pioneers, and high school students joined the Komsomol. In the summer, they were further socialized in summer camps, modeled after the famous Artek camp on the Black Sea. These mostly coeducational environments were a major departure from the gender segregation that had predominated in the region. They inculcated the young generation into a new, more egalitarian system of values.

Conclusion

The photographs presented here are among thousands distributed to foreign press agencies by the Soviet state in the late 1940s. The aim was to impress upon Western readers and governments the USSR’s economic, scientific, and social achievements in the wake of World War II. As specimens of thinly veiled propaganda, the photos can be woven into multiple distinct narratives. They tell of modernization and emancipation on the one hand, and, on the other, of mythmaking to maintain a totalitarian regime. However, it would be a mistake to dismiss them as pure fabrications. Rather, they skillfully merge fact and wishful thinking, showing Central Asian society as government ideologues wanted it to be—and as it indeed was for many women during that tumultuous moment in the region’s history.

Credits and Bibliography

Credits

The photographs showcased here are part of the Soviet Information Bureau Photograph Collection, held and recently digitized by the Davis Center Collection for Russian and Eurasian Studies, H.C. Fung Library, Harvard University.

Web exhibit text by Nargis Kassenova and Svetlana Rukhelman.

Bibliography

Aminova, R. (1962). “From the History of Emancipation of the Women of Central Asia” in Istoriya SSSR, Vol.2, pp. 106-119.

Ewing, E.T. (2006). “Ethnicity at School: ‘Non-Russian’ Education in the Soviet Union during the 1930s” in History of Education, Vol. 35: 4-5, pp. 499-519.

Northrop, D. (2007). “The Limits of Liberation: Gender, Revolution, and the Veil in Everyday Life in Soviet Uzbekistan” in Everyday Life in Central Asia, edited by Jeff Sahadeo and Russel Zanca. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Silova, I. and Palianjian, G. (2018). “Soviet Empire, Childhood and Education” in Revista Española de Educación Comparada, No.13, pp. 147-171.