Central Asia has been at the crossroads of empires and civilizations. The image of its inhabitants has always been multi-faceted and hard to define. Can we have a collective portrait of Central Asians over the ages? Who were the people who mastered the nomadic lifestyle, allowing them to live in the vast steppes of Central Asia? What were the looks and ways of those who loaded camel caravans that journeyed thousands of miles across forbidding deserts? What kind of people traded in its bustling bazaars? What do we know about the women who wove beautiful Central Asian carpets sold in other parts of the world? Who were Soviet Central Asians?

In search of an answer, we explored the collections of Harvard's numerous libraries. We found artifacts that represent different figures and personas populating Central Asia’s history: from mighty Amir Timur receiving guests in his garden, to sunbathing children in a Soviet pioneer camp. We see them through different lenses as well: they appear from under the brushes of Persian miniature painters as well as on the film rolls of Soviet photographers. This diverse range of perspectives not only reveal the differing ways Central Asians have been viewed and viewed themselves through the ages, but also showcases Central Asia as a part of different cultural spheres.

The artworks in this web exhibit come from the Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies Collection at Fung Library, Houghton Library and Widener Library. These and other libraries and museums across Harvard hold a wealth of books, maps, visual materials, and other objects documenting the history and diverse cultures of Central Asia. Taken together, these objects comprise a rich record of the region's past, showing how it has defined itself and functioned as a magnet for exploration, commerce, and cultural exchange. The breadth and depth of the university's holdings on Central Asia make Harvard a major hub for the study of the region.

Love and Glory in 16th Century Central Asia

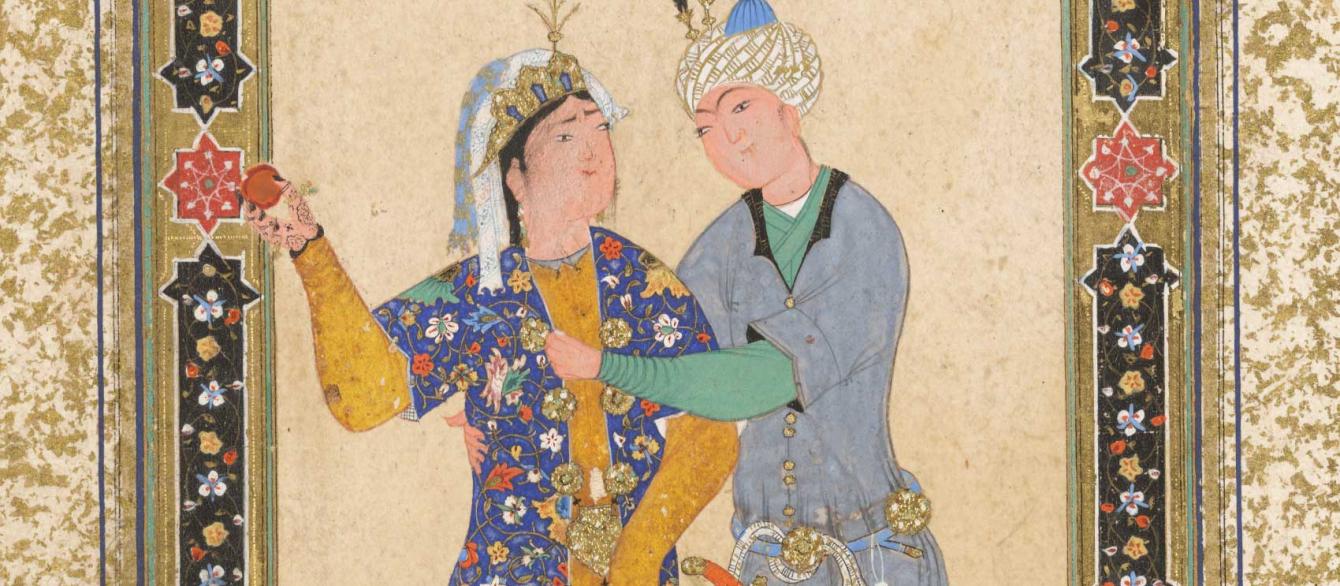

Lovers with Pomegranate (painting, recto; calligraphy, verso), folio from an album, left-hand side of a bifolio, Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of John Goelet, formerly in the collection of Louis J. Cartier, 1958.68.

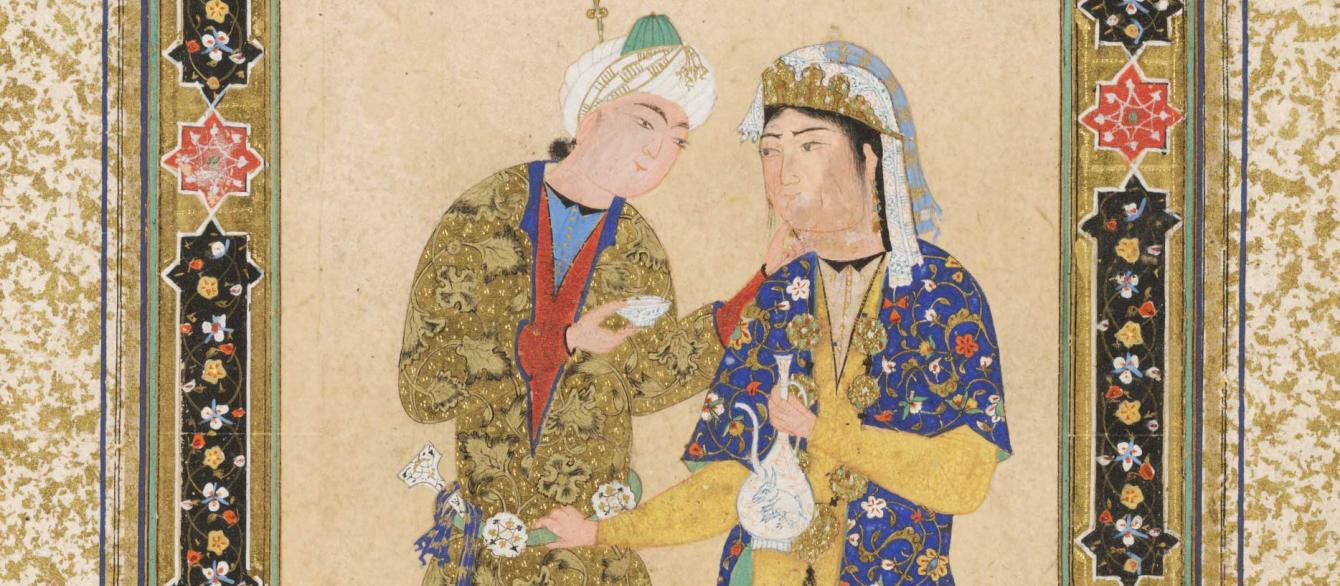

Lovers with Wine (painting, verso); Love Poetry (calligraphy, recto), folio from an album, right-hand side of a bifolio, Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of John Goelet, formerly in the collection of Louis J. Cartier, 1958.67.

Artistically, ancient Central Asia was a part of the Persian cultural sphere. Developed from the late Timurid tradition, the Bukharan school of miniature painting under the Shaybanid rule continued the earlier aesthetics and techniques. Herat painters and calligraphers traveled to workshops (kitabkhana) in Bukhara (modern day Uzbekistan) in the early 16th century. From the mid-16th century, a distinct style evolved. Compared to the Herat tradition, the Bukharan paintings foreground subjects of outdoor amusement and lovers' meetings, favoring the themes of leisure and contemplation. The Uzbek rulers, who sponsored illustrated manuscript books, preferred Persian love poetry and epics, such as the Shahnama and Timurnama.

The first set presents illustrations for Persian love poetry during the mid-16th century. Against a simple backdrop, the two paintings showcase the affectionate interaction between the lovers and their exquisitely detailed costumes. These two sixteenth-century illustrations from Bukhara, attributed to the Persian calligrapher Mir `Ali Haravi, reflect a world that appreciated romance and elegance. The figurative depiction of people and of wine-drinking gives these miniatures a special place in the history of Islamic art.

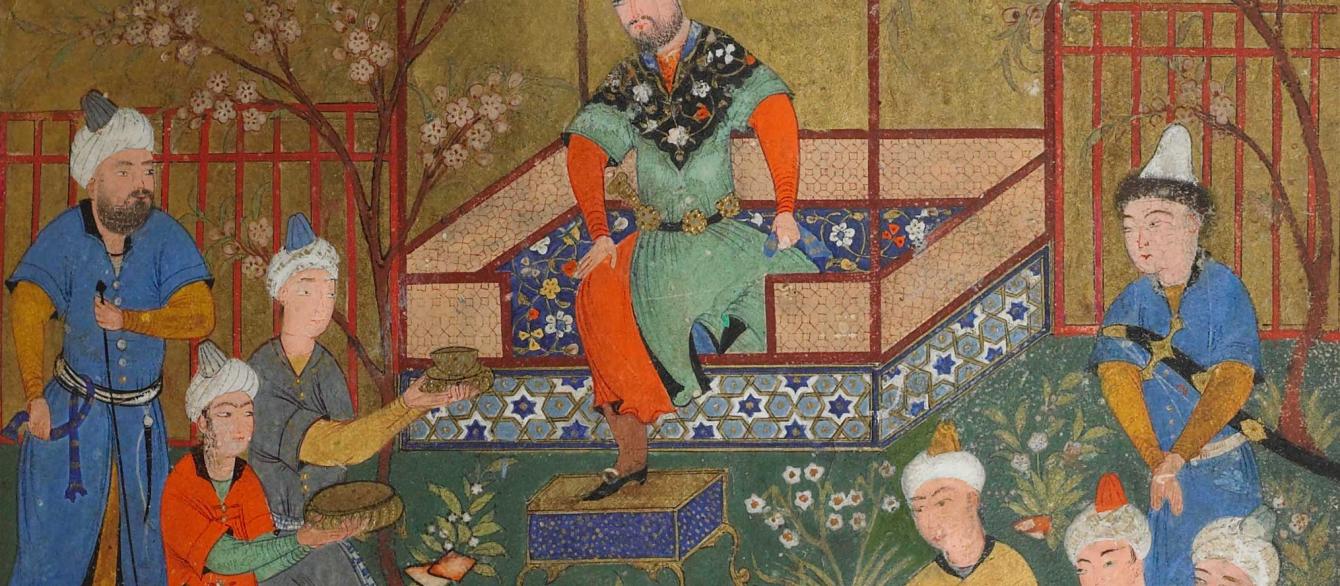

Timur Holding court in a Garden (painting, recto), Text (verso), illustrated folio (35) from a Manuscript of the Timurnama by Hatifi, Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Gift of John Goelet, 1957.140.35.

The second set depicts a lively gathering held by Timur, the founder of the Timurid dynasty, in a garden setting. The images include drinking, music playing, and dancing, which were both popular activities of courtly life and recurrent subjects for paintings under the Timurids since the early 15th century. Timur was a tough conqueror, but also an avid garden-builder. Luxurious gardens, meant to represent “paradise on earth”, embellished Samarkand like a necklace. This 16th-century illustration from a manuscript produced in Bukhara shows Timur holding court in one such garden.

(Credits to Yue Xie, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard University)

Orientalism and Global Trade in the Russian Empire

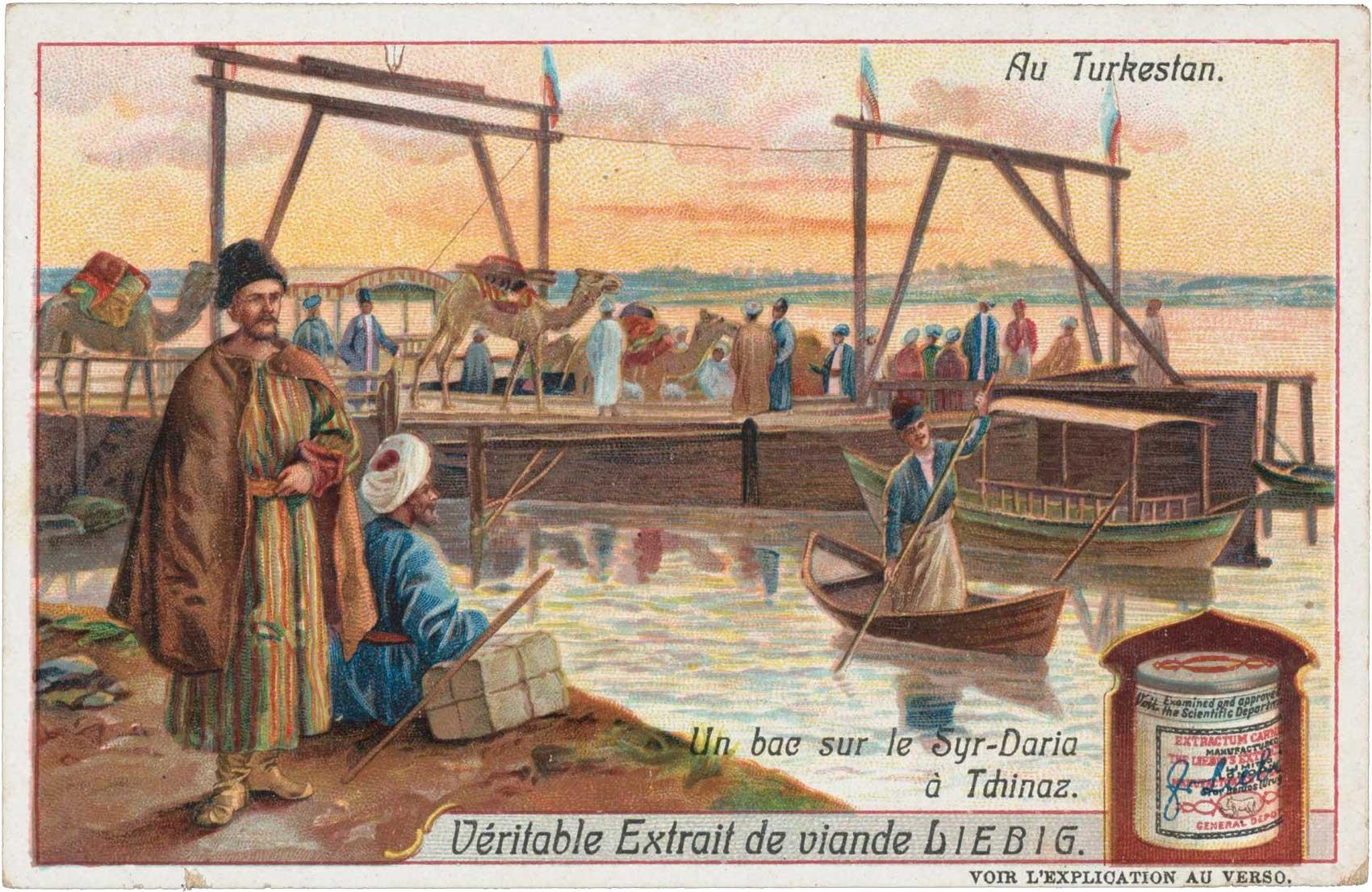

Un bac sur le Syr-Daria à Tchinaz. [A ferry on the Syr-Daria at Chinoz.]

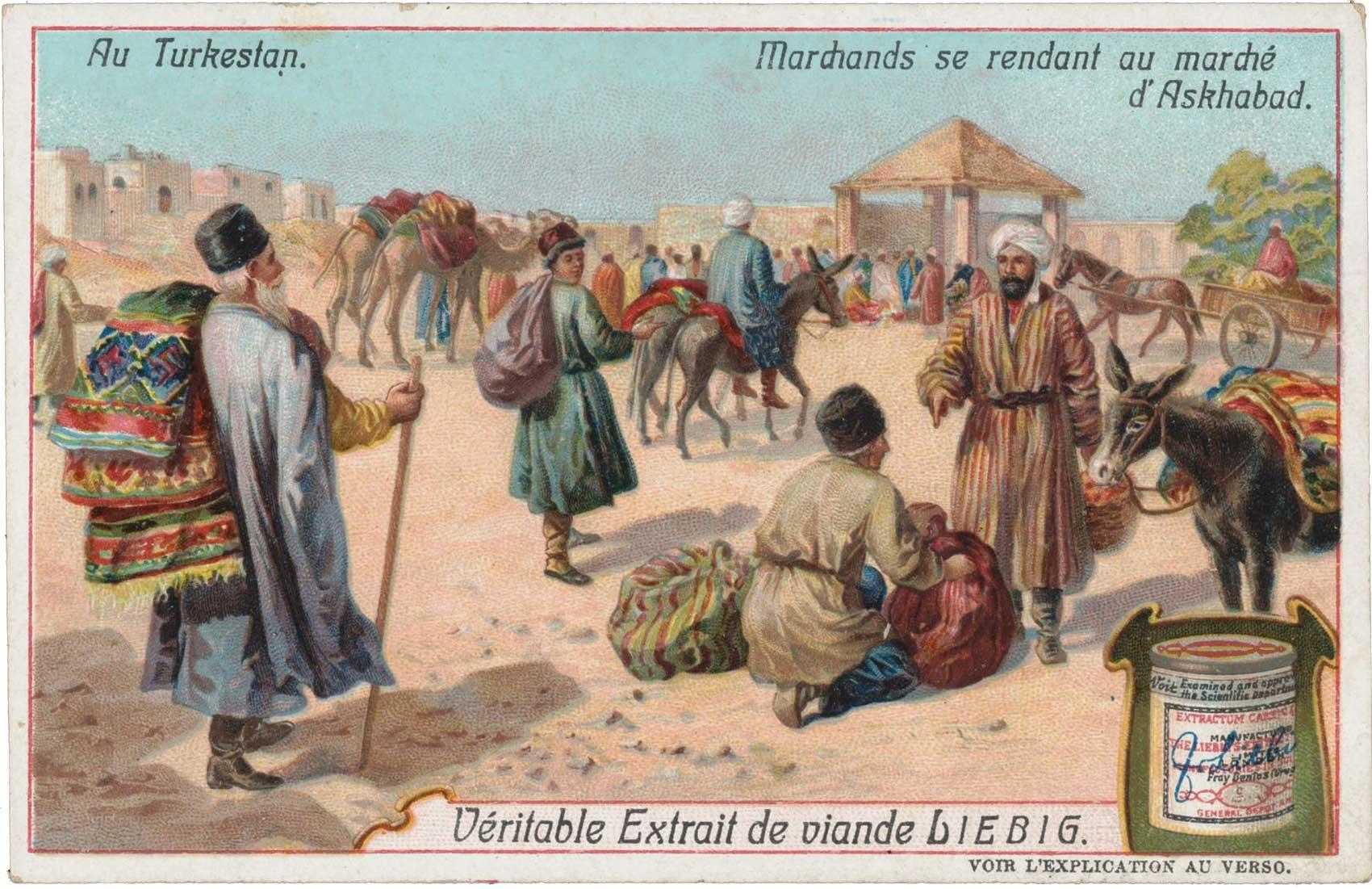

Marchands se rendant au marchè d'Askhabad. [Merchants on their way to the Ashkhabad market.]

When European adventurers traversed the Caspian and set foot in so-called “Russian Turkestan” in the 19th century, they saw a vast curious land with unfamiliar peoples, landscapes and cultures confounding their senses. They created maps and images of the region. The remarkable images we have here come from the “Turkestan” series of collectible picture cards, created by Liebig's Extract of Meat Company and added to packaging of products sold on the French market. Coming from the age of globalism, it shows how Central Asia was viewed as part of the Orient by those coming from the West and incorporates them into a global business network. It also sheds light on facets of ordinary lives at the turn of the 20th century, from those of merchants journeying down the Syr-Darya, to explorers marveling at ancient ruins in Samarkand.

Women’s Revolution in the USSR’s East

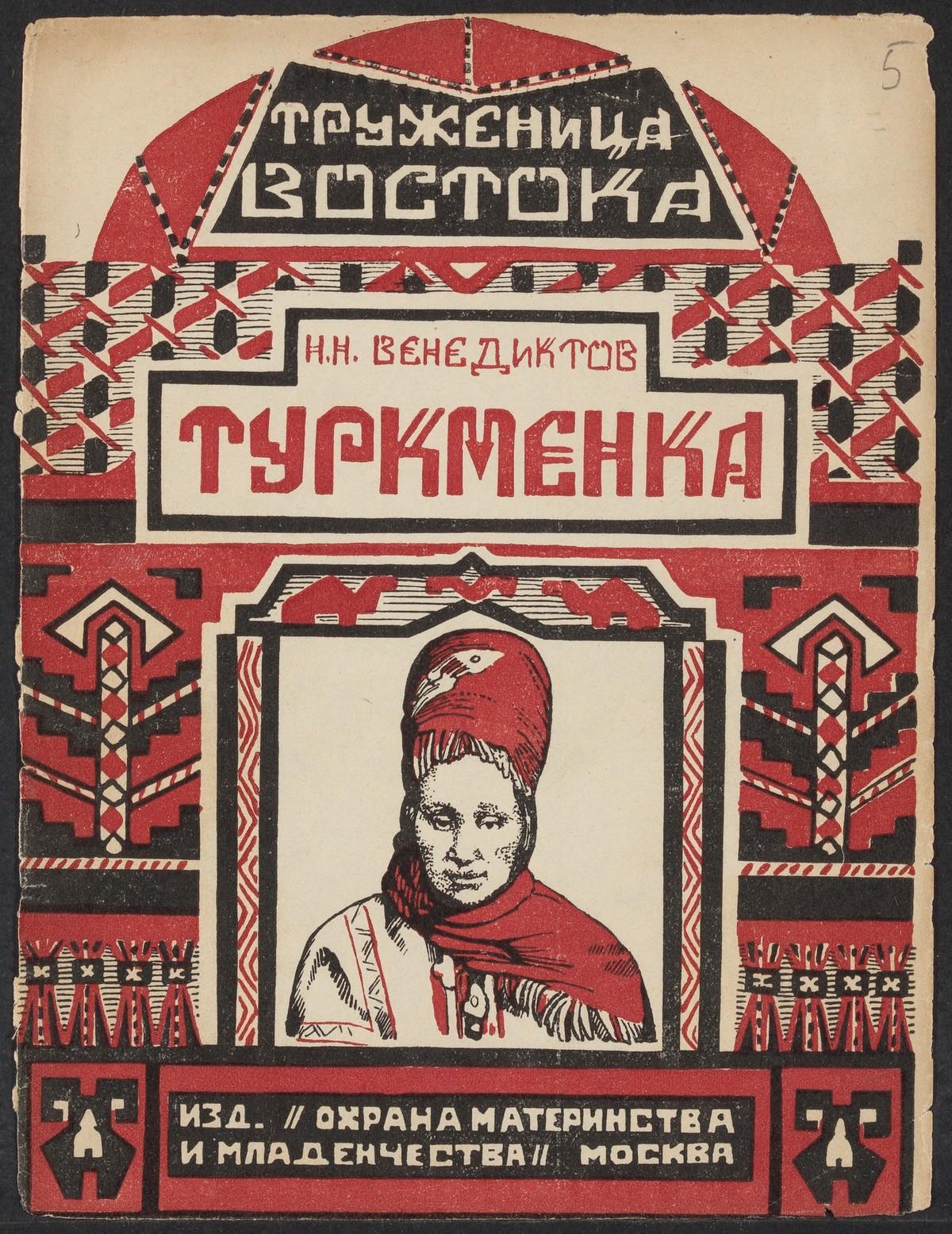

Truzhenitsa vostoka—Turkmenka. [Woman Laborer of the East—The Woman of Turkmeniia.]

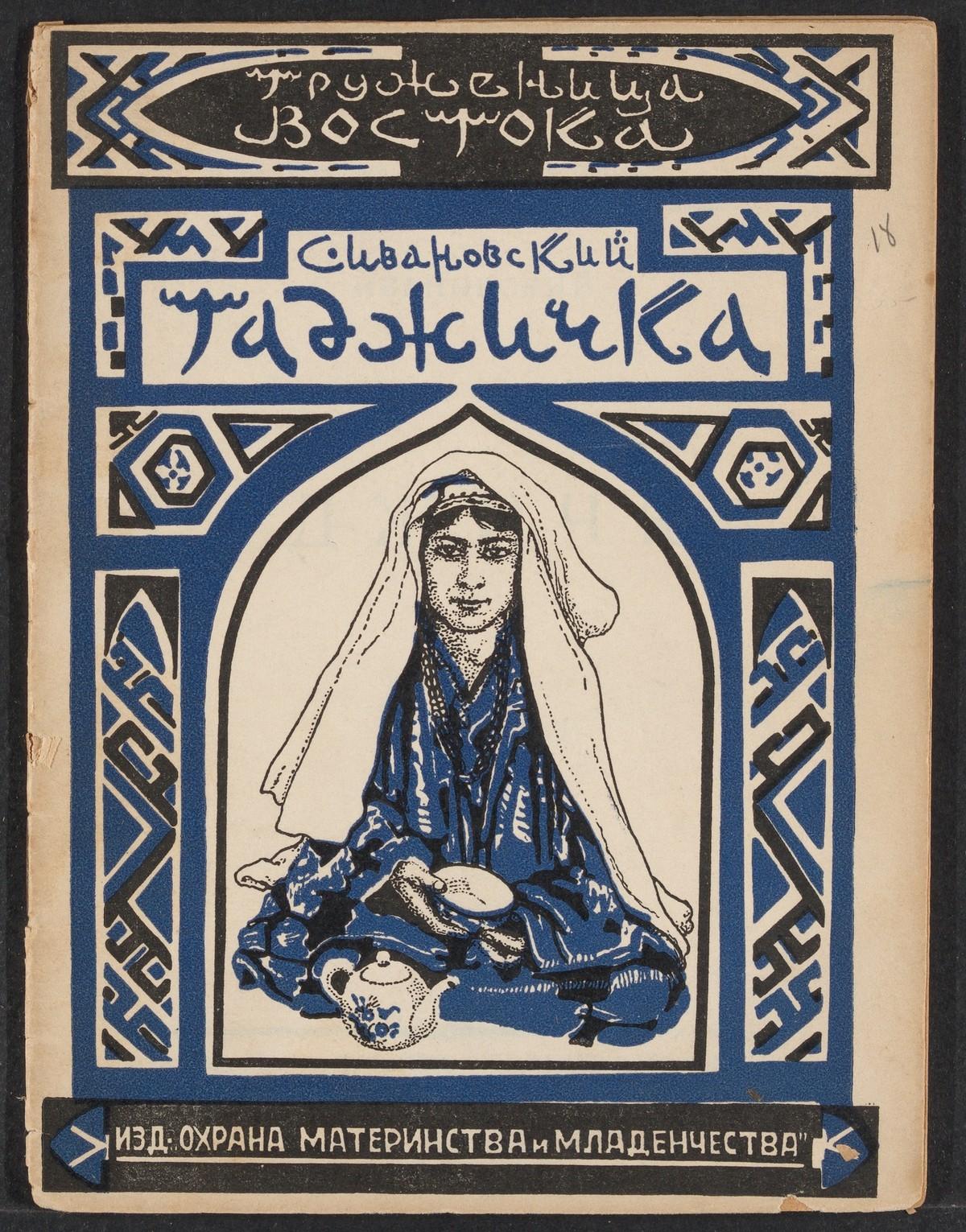

Truzhenitsa vostoka—Tadzhichka. [Woman Laborer of the East—The Woman of Tajikistan.]

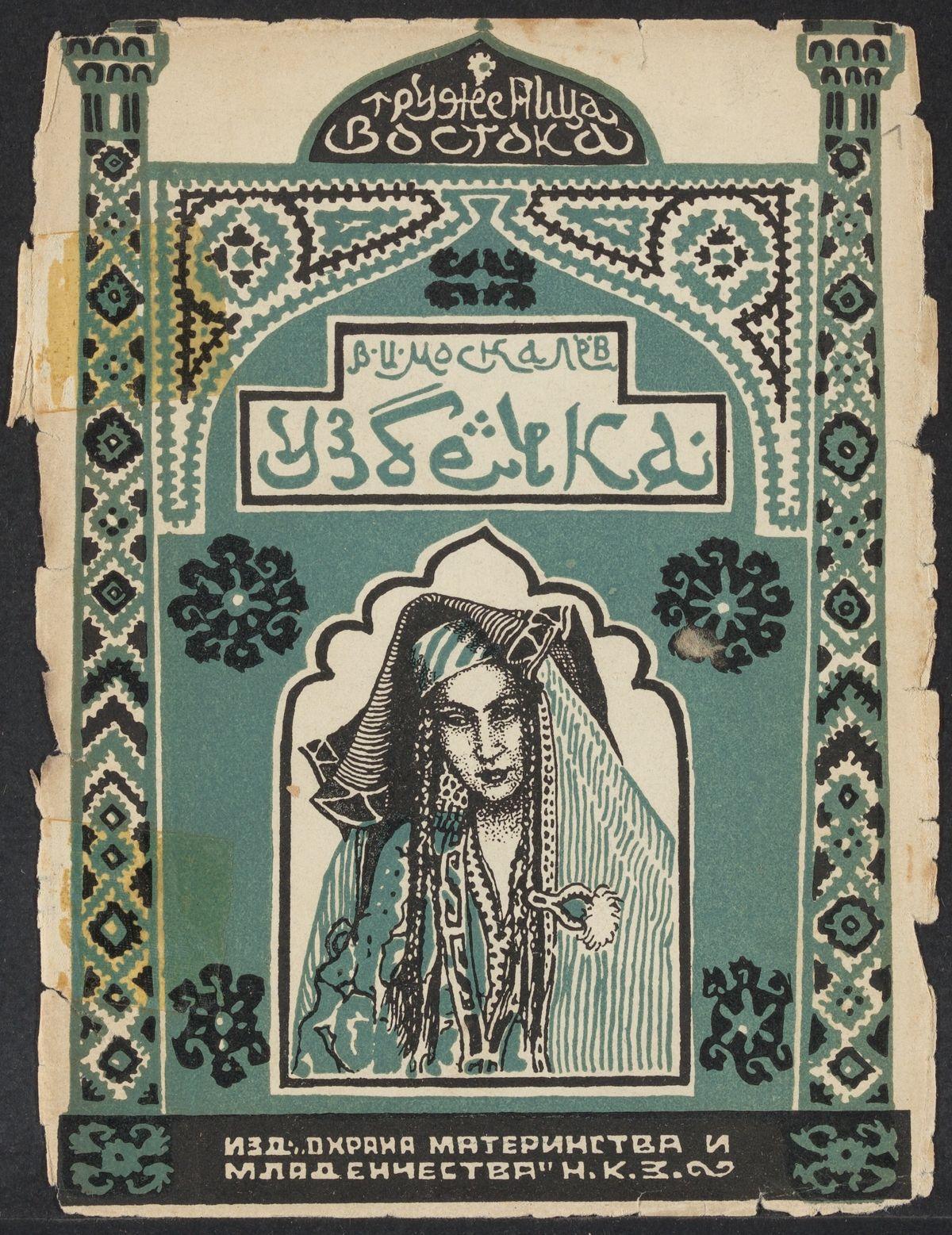

Truzhenitsa vostoka—Uzbechka. [Woman Laborer of the East—The Woman of Uzbekistan.]

During the early Soviet period, the Bolsheviks aimed to create a more equal society. Part of this campaign was the emancipation of women. Central Asia, where reforms were particularly drastic, turned into a showcase of the Soviet modernization project.

Here we have covers of the pamphlets “Turkmenka”, “Tadzhichka,” and “Uzbechka,” published in 1928 as part of a series describing the conditions of life for women from various ethnic groups and regions all over the Soviet east. (The series title, "Truzhenitsa vostoka," translates to "Woman Laborer of the East.") They show women in traditional dress against a background of stylized Central Asian carpet ornaments. These pamphlets educated the masses on conditions requiring change, and their publication accompanied a slew of sweeping reforms. For instance, in 1926 the Turkmen Central Executive Committee adopted a decree banning polygamy and child marriage.

The Soviet Information Bureau issued the photo below, showing Central Asian women engaging in textile production in the post-war years. The focus here shifts from “liberating” women from old customs to employing them in the factories and incorporating them into the mainstream workforce. Viewing the two sets of images together, we can observe the amazing shift in lifestyles of two generations of Central Asian women.

Curious to know more about the pamphlets? Check out Christine Jacobson’s digital project: Working Women of the East

Carpet Makers of Turkmenistan.

The Soviet Cycle of Life

Intended to document the reconstruction of the Soviet Union following World War II, the Soviet Information Bureau produced thousands of 6,000 black-and-white photos, recording daily life, culture, and news at the start of the Cold War. The range of the subjects is vast, portraying well-known figures like Joseph Stalin and Dmitrii Shostakovich, as well as ordinary people from all parts of the Soviet Union, including the Central Asian republics.

Departing from ideological caricatures, these officially-made but nonetheless true-to-life portraits of Central Asians allow us to catch a glimpse of work and recreation in postwar Central Asia. They reflect some of the best aspects of life in the region at this time, as well as hint towards what the state looked forward to. They range from shots of vacationing children to proud steel workers, depicting people from all stages of an ideal, Soviet way of life.

Pioneer camp on Lake Issyk-Kul.

Pioneer summer camps on Lake Issyk-Kul, the gem of the Tian Shan mountains, were part of the USSR-wide “archipelago” of children’s institutions aimed at bringing up a generation of new Soviet people. Pioneer camps were a staple of the “happy Soviet childhood,” with a blurry border between the mythical and the real.

Industrial construction in the steppes of Kazakhstan.

Post-World War II reconstruction jumpstarted metallurgical industries in the Soviet East. In Kazakhstan, steel production developed quickly thanks to an abundance of coal and ore deposits. This contributed to the success of a larger Soviet campaign to increase steel production by about 20 million tons per year in the decade after the war. Large numbers of Kazakhs participated in this campaign, forging both metal and a steel-spirited working class.

Looking Forward...

Following the collapse of the USSR, the five Central Asian republics emerged as independent states. Their new roles in the international community make studying them all the more relevant. Today, the Davis Center has a dedicated Program on Central Asia that conducts research and hosts events related to this region.

Image Details

Links to the full-size images and information are available below.

- Lovers with Wine & Lovers with Pomegranate

- Timur Holding Court in a Garden (1) & Timur Holding Court in a Garden (2)

- Un bac sur le Syr-Daria à Tchinaz

- Marchands se rendant au marchè d'Askhabad

- Pamphlets: Truzhenitsa Vostoka

- Carpet Makers of Turkmenistan

- Children's Sanatorium in Kirghizia

- Industrial Construction in the Steppes of Kazakhstan