This newly available archival collection—gifted to the Davis Center Collection at Fung Library in 2022 by Christopher Shepard, grandson of Marina Kazbegi and himself a member of the Georgian diaspora in the U.S.—gives us insight into the life of two of the most prestigious noble families in Georgia at the turn of the 19th century. Consisting of correspondence, photographs, and unpublished memoirs, the archive serves as a striking record of the Kazbegi and Dadiani family histories from the late 1800s to their exile and emigration to the U.S. The collection is now described in a detailed online finding aid and is open for research. The 70 photographs and four photograph albums have been digitized alongside their captions and can be browsed and keyword-searched online.

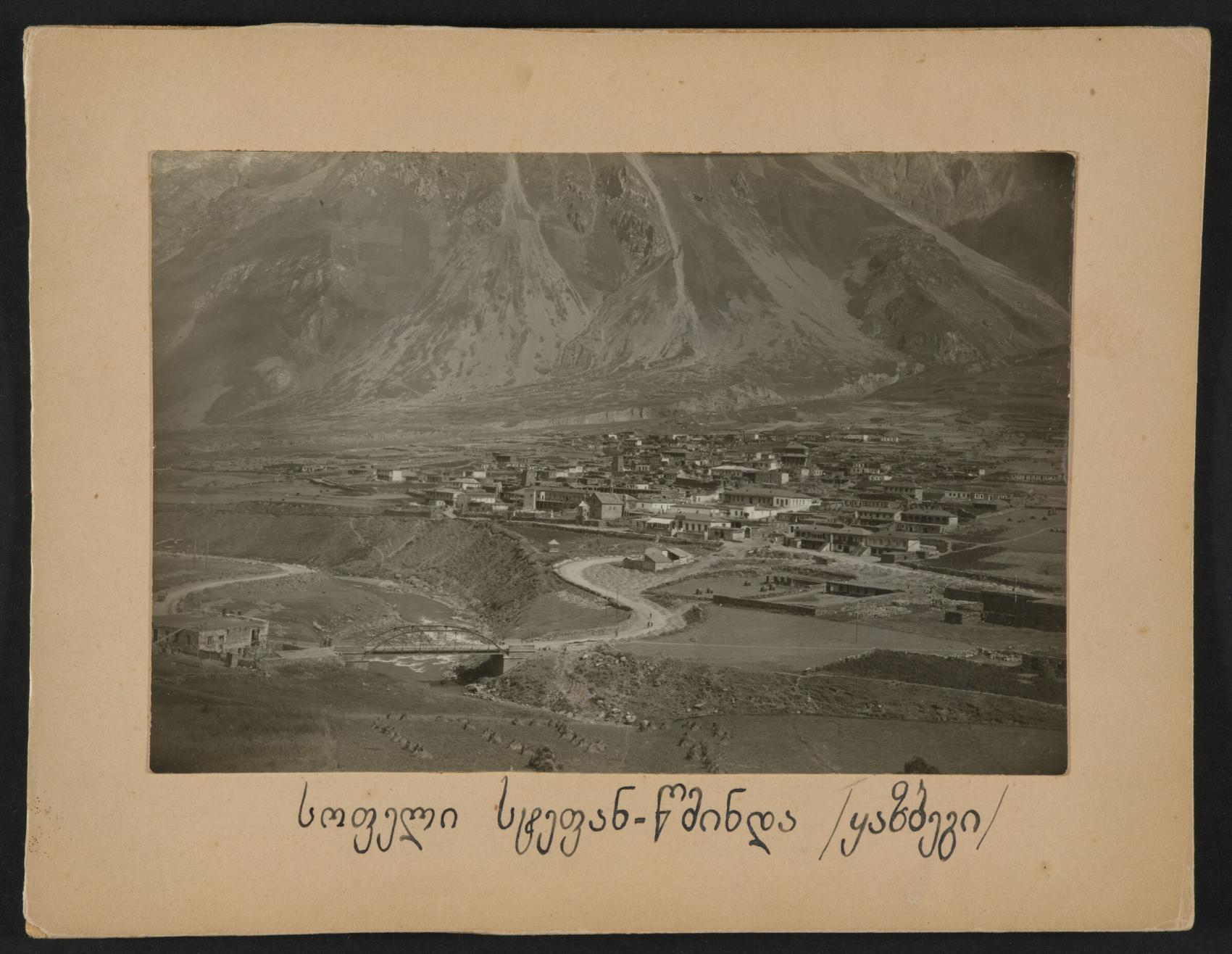

The Kazbegis came from the northern mountainous region of what was formerly the Georgian kingdom of Kartl’Kakheti (annexed by Tsar Paul I in December 1800). On our map, you can see the Georgian Military Highway heading directly north from Tiflis to Kazbegi (marked as M.Kazbek on the map). Also known as Stepantsminda (St. Stephen), this was the summer home of the Kazbegi family.

Russia in Europe Part IX and Georgia. Caucasus, Circassia, Astrakhan, Georgia.

The Dadianis, with whom the Kazbegis became linked by marriage, were also a princely family. Taken under the Russian empire’s protection in 1803, the Dadianis continued to reign over their kingdom of Samegrelo (Mingrelia) in western Georgia until 1867 when the principality was formally abolished. Both the Kazbegi and the Dadiani families were quickly absorbed into the Russian noble class as hereditary nobility, a reward for their willingness to serve the Russian empire. They prospered in an empire that preserved their status, protected their property, and granted them educational and social privileges equal to their princely Russian counterparts. Their residence—the Dadiani Palace pictured here—was built in the 17th century by British architect Edwin Race, and restored in the 19th century. It is now a museum.

Dadiani Palace in the late 19th century.

Georgia was strategically important to the Russian empire. It bordered the hostile Muslim empires of Iran and Ottoman Turkey to the south as well as the North Caucasian Muslim peoples to the north, who fought for the first six decades of the 19th century against Russian conquest (known as the Caucasian War). The town of Kazbegi was one of the more important post stations on the Georgian Military Highway that connected Russia with Transcaucasia. Mikhail Lermontov, in his poem Demon, described the highway as a savage and dangerous road winding among the lofty mountains of the Caucasus. Many of Georgia’s own 19th-century poets such as Alexandre Chavchavadze (1786-1846) characterized the Georgian Military Highway as a channel of enlightenment from the north. Dominated by Mount Kazbegi and its glaciers at over 16,500 feet, the town was the famous gateway between Russia and Georgia. The Terek (Tergi in Georgian) river flows through the town and gave its name to the famous group of Georgian intellectuals in the second half of the 19th century who received their education in Russia. They were called the tergdaleulebi, or “those who had drunk from the river Terek.”

Darial Gorge, one of only two usable crossings through the Greater Caucasus Range and site of the vitally important Georgian Military Highway.

Gergeti Gorge and tower, just across the Terek River from Kazbegi village and south of the Darial Gorge. The Tower, built around the 14th century, typified the wild landscape portrayed by Lermontov.

The Kazbegis originally went by the name Chopikashvili. They had enriched themselves through the control of trade on the Georgian Military Highway as it passed through the Darial Gorge. They gained favor with the tsar when Gabriel Kazbegi supported King Erekli II’s decision to establish Georgia as a Russian protectorate. Kazbegi was instrumental in allowing Russian troops to enter the country through the Darial Gorge unopposed. The family name gained further fame in Georgia due in part to the writings of Alexandre Kazbegi (1848-93), a novelist who lionized the mountain Georgians in the Khevi district, of which Kazbegi was a part. His novels were a critique of Russian colonialism, and his heroes were rebels who resisted a cruel tsarist system. The Kazbegi family estate was in the town and had its own church. It must have been a popular place to rest for travelers, poets, generals, and writers who were passing through on their way to the welcoming arms of Tiflis, or northward to Vladikavkaz, the “Lord of the Caucasus,” a reminder of Russia’s imperial power in the region. Alexander Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov, Leo Tolstoy, and European travelers, too—like Alexandre Dumas, John Steinbeck, and Lord Curzon—all passed through Kazbegi on their travels through Transcaucasia.

Kazbegi village, also labelled here as "Stepan-tsminda."

The Kazbegi estate.

The biographical materials in this collection include legal documents, correspondence, visiting cards, postcards, and family pictures. Gathered in two original family albums (and four more collated from other photographs), the images tell us much about the gilded life of the Georgian aristocracy in the late 19th century and their subsequent exile in Europe and the U.S. after the Russian Revolution. The bulk of the collection follows the life of Nina Dadiani, who married Konstantine Kazbegi in 1914, and their daughter, Marina. Following Konstantine’s death in an automobile accident while serving as an aide to the tsar in 1915, Nina and Marina spent much of their time on the Kazbegi family estate in the shadow of the Darial Gorge and along the banks of the Terek.

A family outing on the southern slopes of Mount Kazbegi, 1912.

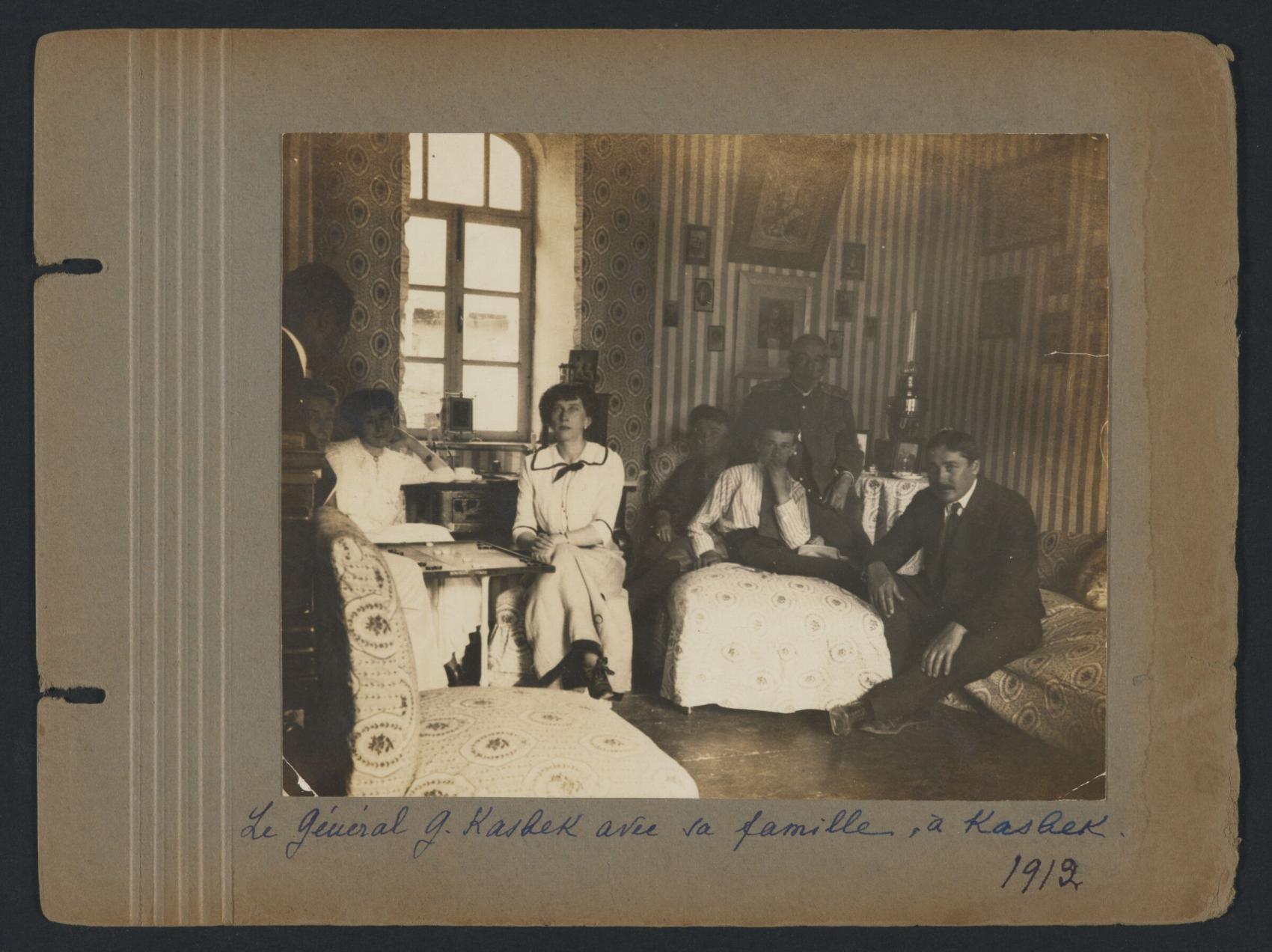

General Giorgi Kazbegi with members of his family in his home in Kazbegi, 1912.

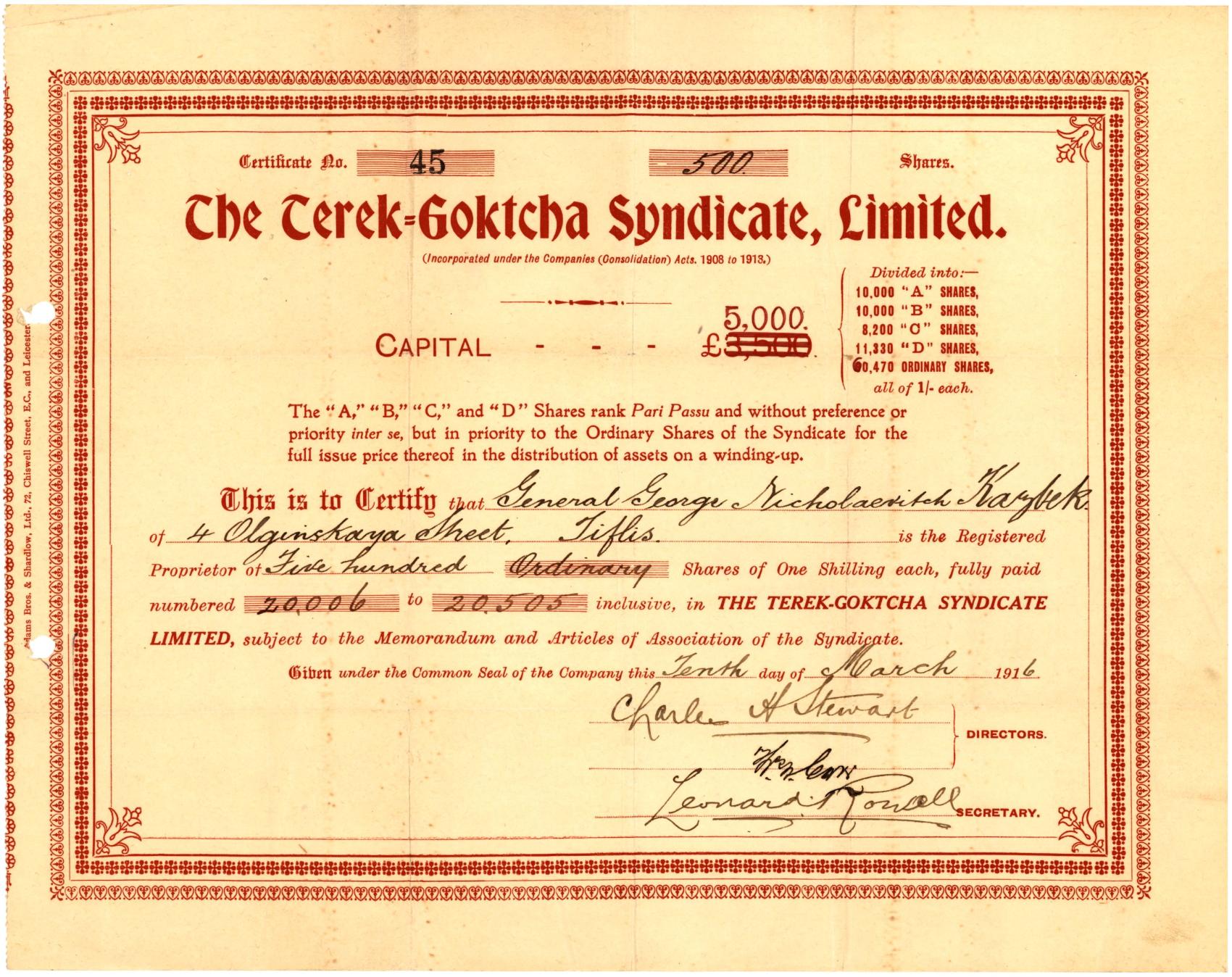

The photographs of the Kazbegis before exile in 1921 show the family on picnics, playing tennis, pottering around their estate, hunting, and spending time in their house in Tiflis (during the harsh winters in Kazbegi when the Georgian Military Highway was closed). Many Georgian nobles failed as landowners and farmers after the end of serfdom in Georgia in 1864, but the Kazbegis had interests in hydro-electric power development on the river Terek (they sold a concession to a British company in 1912) as well as in a Georgian oil-producing and in a joint stock company.

A stock certificate issued to Giorgi Kazbegi by the Terek-Goktcha Syndicate, the company planning on developing a hydro-electric dam on the Terek.

Like all Georgian princely nobles who depended on tsarism for their survival as a privileged class, the Kazbegis became well integrated into imperial Russian society. Konstantine’s father, Giorgi, was typical of the imperial Russian service elite. Born in Kazbegi, he was sent to train in a cadet corps in Voronezh before graduating from the General Staff Academy in St. Petersburg. After a stint in his native Georgia and some combat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, Giorgi served as the commander of the Warsaw and then the Vladivostok fortresses. It was while serving at the latter that Giorgi managed to peacefully quell rebellious troops during the 1905 revolution. Returning to Georgia in 1907, Giorgi dedicated himself to Georgian affairs and his estate. He developed a rug-weaving school and built a day school on his estate. He became president of the Georgian Red Cross and chairman of the Society for the Spreading of Literacy Among Georgians, the leading organization of Georgian writers and intellectuals attempting to preserve Georgian identity and culture. All this suggests he was a Georgian patriot who wished to protect Georgian identity and culture but keep it within the empire.

Giorgi Kazbegi on his estate.

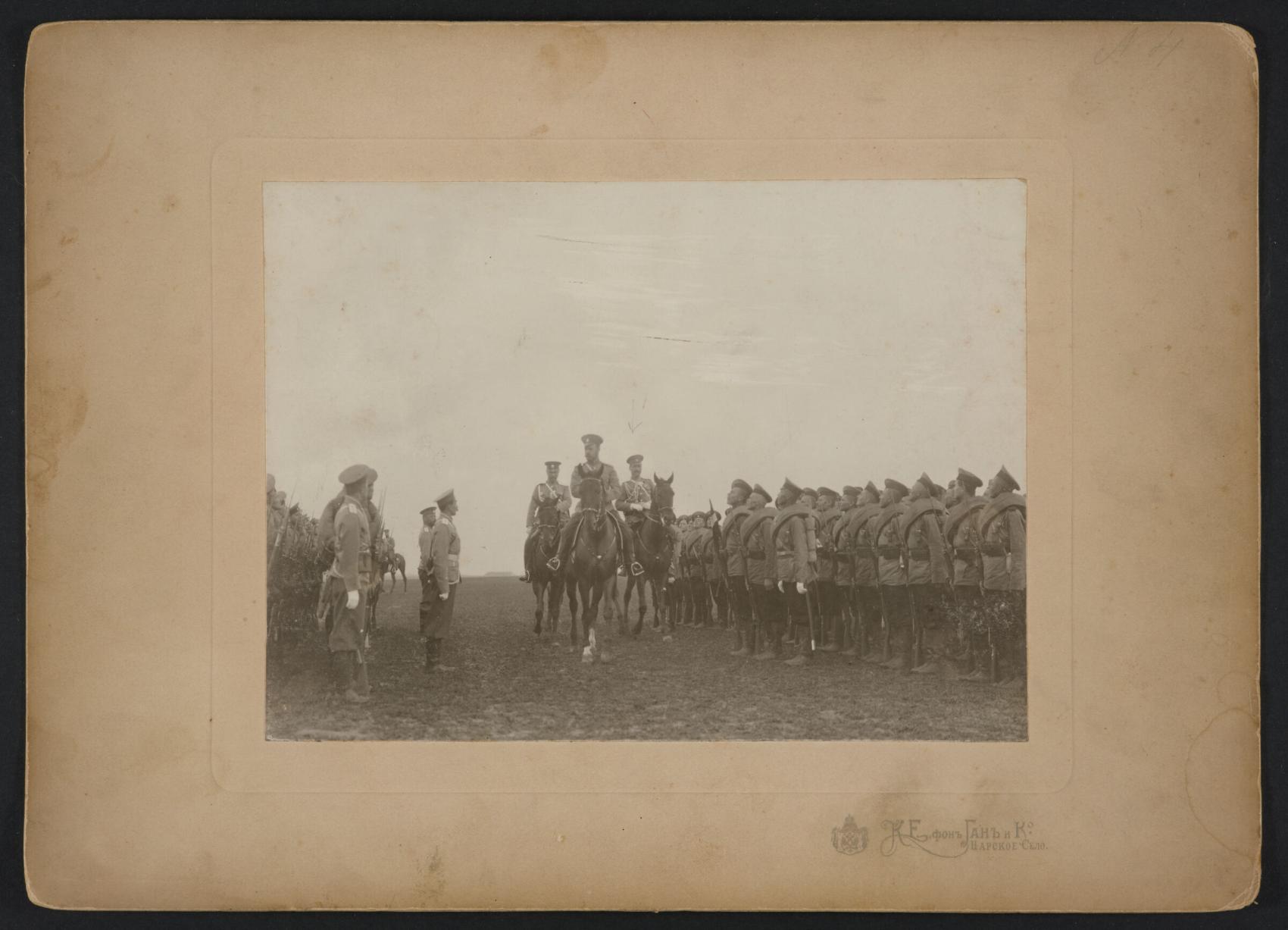

Georgia’s leading nobles served in the imperial army and those at the princely level (kniaz’ in Russian or in Georgian tavadi) often had close personal ties to the Russian royal family through marriage and other relationships. There are several photographs of Giorgi’s sons Konstantine and Alexandre Kazbegi in the retinue of Tsar Nicholas II. Konstantine Kazbegi’s and Nina Dadiani’s daughter, Marina, was one of the tsar's last godchildren.

Tsar Nicholas II (mounted center) inspecting troops alongside aide Aleksandre Kazbegi (mounted right).

While the family was able to reap many rewards from proximity to the court, it became damning after the revolutions of 1917-18 and the disintegration of the Russian empire. These cataclysmic events ended the Georgian aristocracy’s leisurely life. The Georgian nobility was one of the pillars of the tsarist system in Georgia, but the tsarist sosloviia (estates) quickly collapsed. Georgian nobles were reduced to penury and in some cases exile. Land reform introduced by the Georgian Democratic Republic (1918-21) greatly reduced the size of the noble classes’ properties including those of the Kazbegis and Dadianis.

On May 26, 1918, Georgia, with the support of the German government, declared independence. Germany wanted possession of the strategic Transcaucasian railway but was forced to withdraw in November 1918 after losing World War I. German troops were replaced by British forces (until the summer of 1920) and Georgia was finally recognized de jure by the Supreme Council of the Allied Powers on Jan. 27, 1921. Kazbegi became a dangerous frontier town in 1918-21, adjacent to the newly formed Mountain Republic of the North Caucasus and a crucial borderland between Red Russia and independent Georgia. Red and White Russian forces fought over the North Caucasus during the Russian civil war and they were perilously close to Kazbegi. It became unsafe for noble families like the Kazbegis and Dadianis to stay there.

With the fall of the Georgian Democratic Republic in February-March 1921, the Red Army marched through Kazbegi to the southern plains of Georgia. The Kazbegi and Dadiani family estates were confiscated by the new authorities (the Kazbegi estate is now the museum of local 19th-century novelist Alexandre Kazbegi). It is difficult to trace the exact path members of the family took after fleeing Georgia. Giorgi Kazbegi died in April 1921 in Constantinople. Giorgi’s daughter-in-law Nina and her own young daughter, Marina, presumably traveled with him before moving to Central Europe. Many of the Georgian nobility joined the sizable White Russian émigré communities in Paris, but Nina and Marina appear in various cities in the east of what was then Germany, such as Dresden and Tillowitz before they settled in Berlin.

Nina Dadiani and her daughter, Marina Kazbegi, in Tillowitz, Germany (present-day Tułowice, Poland), 1937.

In many ways, these aristocratic families were well-prepared for exile. They were educated based on European models and fluent in multiple languages. Giorgi knew French, Georgian, and Russian and was able to read English, Italian, and some Japanese. He spent three years in the 1880s traveling across Europe and America. Giorgi’s daughter Elena Kazbegi-Gamkreli (known affectionately among her family and friends as Elou) and Nina, her sister-in-law, were also multilingual.

Even with this education, life in exile was not easy. The collection documents several of Nina’s attempts to discover the fate of relatives and friends. For example, there is a response to an inquiry about the fate of a cousin from Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg, then Nazi Germany’s ambassador to the Soviet Union and later a conspirator against Hitler. There are scattered postcards, correspondence, and two partial biographies of family friends. Berlin became a home of sorts. The Kazbegi/Dadiani family joined the German aristocracy through the marriage of Marina to Helmuth von Moltke (1913-1944), who was related to a long line of famous German military strategists. After Helmuth’s death, Marina married Paul Goerz Langfeld in 1947 and emigrated with him to the United States in 1953. Various newspaper clippings and tourist brochures relating to Georgia in general and the former Kazbek estate specifically, which were collected throughout the Soviet period indicate Marina’s continued interest in her Georgian heritage. She was also active in promoting her adopted home and helped to found and organize the annual Quadrille Ball of the Germanistic Society of America. Family members participated in the activities of the small Georgian diaspora, consisting mostly of former noble families who organized their own series of balls in the 1930s—known as the Allaverdy Balls. Series 4 in the archive provides multiple photographs of the family’s social life in Kazbegi, Petrograd, Europe, and the U.S.

The Dadiani princely family, like the Kazbegi family, tried to flee abroad. The lives of the four children of Nikoloz Dadiani-Mingrelski, the last of the princely family to govern the principality of Samegrelo, illustrate the often tragic fate of Georgia’s noble families. His daughter Ekaterine Dadiani died in childhood; Nikoloz’s son (also Nikoloz) died in a Bolshevik prison. Salome-Mia, his second daughter, fled to France. The Dadianis who remained in the USSR became ordinary Soviet citizens. Menik, Dadiani-Mingrelski’s illegitimate daughter, lived in Georgia. Her son Dadash was executed by the Bolsheviks in the 1920s. The writer and dramatist Shalva Dadiani (1874-1959), also a scion of the princely Dadiani family, had better luck and ended his life a well-respected Soviet writer. A street is named after him in Tbilisi. Eleesa Dadiani (b. 1988) can trace her ancestry to the Dadiani-Mingrelski house. She is an art gallery owner based in London.

The Kazbegi-Dadiani collection is a rare and rich source for the study of the Georgian nobility’s life in the final decades of the Russian empire, as well as in post-revolutionary exile in Europe and the United States. It is an important addition to the Harvard Library’s holdings on Georgia that illuminates the life of the Georgian diaspora in the U.S. The Davis Center's Program on Georgian Studies has developed a website on the history of this diaspora. The Kazbegi/Dadiani archival collection is open to students and scholars at Harvard and beyond.