The continued flow of oil export revenues into Russia is blunting the impact of Western sanctions. At today’s prices, Kremlin tax receipts on export oil alone will cover 70% of Russia’s Federal Budget for 2022. The most obvious remedy to this problem—a full embargo on Russian oil exports—continues to face resistance from some European policy makers. They fear an oil supply shock would trigger a recession that, in turn, could undermine the Western unity needed to counter Russian aggression.

This paper makes recommendations on how to structure an oil embargo strategy in a way that enhances its economic impact. These recommendations include a proposal for a smart embargo option that could stem the flow of Russian tax revenues from oil exports while also averting a politically risky global supply shock. What is more, it would also fund Ukraine reparations at Russia’s expense.

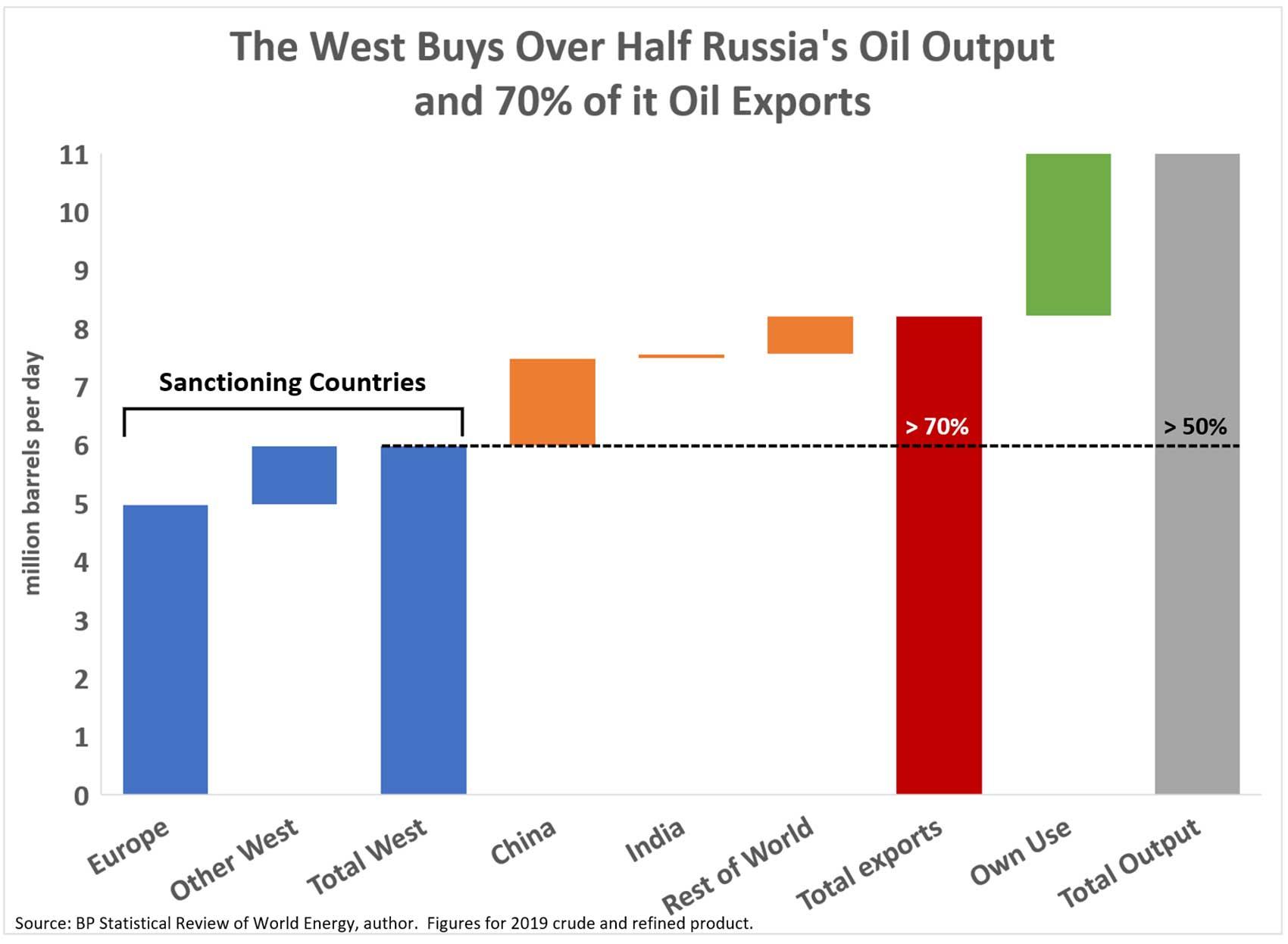

These recommendations take advantage of certain structural vulnerabilities in the Russia oil industry—largely overlooked in the current sanctions debate—that severely limit Russia’s ability to redirect or reduce the 6 million barrels a day it exports to the West—over half its total output. Russia itself consumes around a quarter of its own output. The balance, however, must be exported (Figure 1). China buys less than 20% of these exports, while the West normally absorbs over 70%. These Western imports represent more than half Russia’s entire oil output.

Figure 1

In the event of an embargo, Russia has threatened to redirect its Western export volumes elsewhere. But these “export substitution” threats are hollow—the volumes are far too large to redirect. Russia’s Western export volumes are far too large for China and India to absorb without abandoning their practice of diversifying supplier risk and relying on Russia for nearly half their oil imports. Significant infrastructure and logistical constraints also limit Russia’s ability divert oil East. And if the West imposes secondary sanctions on any enablers of Russia’s seaborne oil trade, Russia would struggle to redirect more than a fraction of its Western exports.

If export substitution is not possible, Russia’s only real option under a Western embargo would be to leave the banned oil in the ground. This would mean “shutting in” more than half its current output. That’s an immense quantity of oil, equal to roughly 6% of global output. Such a scenario would be severely damaging to Moscow for several reasons, some self-evident others less so. Most obvious would be the loss of vital export revenues. While these might be offset by higher prices for Russia’s few remaining exports, the offset would likely be partial and short-term only.

Less evident than revenue loss, however, is the severe damage an extended, large-scale shut in would do to Russia’s upstream production capacity. It could render tens of thousands of marginal wells uneconomic and compromise complex pressure management systems at the field level. This risk is well appreciated by Russian reservoir engineers, but less evident to Western policy makers. Additionally, this could also deeply undermine political support for the Putin regime in Russia’s oil producing regions.

In the event of an embargo, Russia has threatened to redirect its Western export volumes elsewhere. But these “export substitution” threats are hollow—the volumes are far too large to redirect.

A major shut-in would also erode Russia’s standing in OPEC+ and put Russia’s export market share at risk. Finally, it would erode the mainstay of Russia’s centralized, rent-gathering economy that helps enable an authoritarian form of government.

If export substitution is a chimera and a large-scale shut-in potentially catastrophic, Russia is far more dependent on the West to absorb its oil than many Western policy makers may realize. This dependency gives the West significant bargaining leverage—but only if it acts collectively. Properly exploited, it can be used to design smart oil sanctions that achieve Western objectives while minimizing self-harm.

There are different ways to exploit this leverage, such as imposing a special export tax. This paper proposes augmenting a standard embargo with an “oil-for-reparations” smart embargo option that allows for controlled export sales while severely restricting the proceeds remitted to Russia.

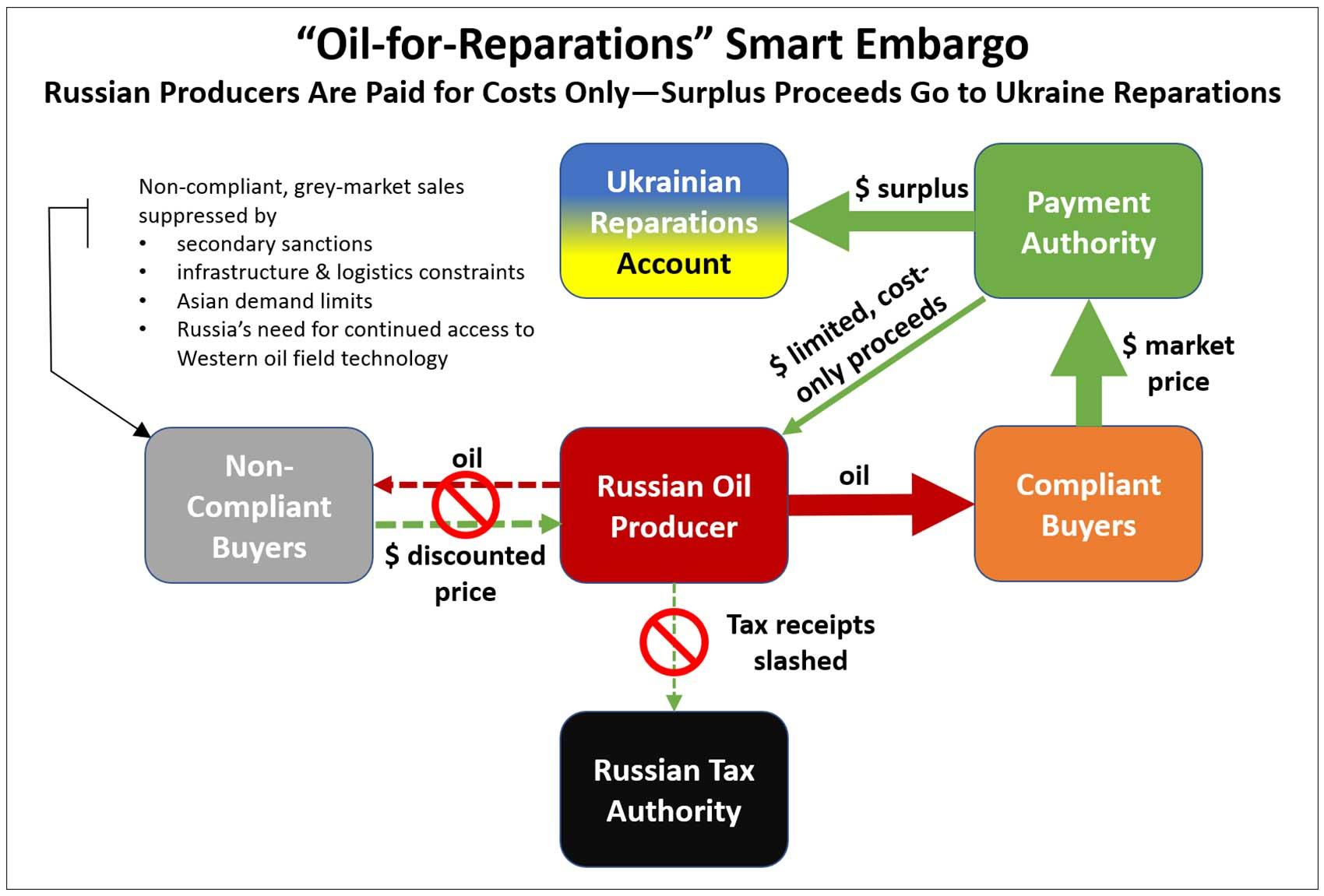

Under this framework, the Western governments would agree to proceed with a full embargo of Russian oil exports (Figure 2). But the embargo would include a special provision that would allow Russian producers to keep exporting oil, provided all proceeds are channeled through a special Payment Authority established by the West. The Payment Authority would remit a portion of the sales proceeds back to the Russian producer—enough to cover average production costs excluding all Russian taxes, but nothing more.

Figure 2

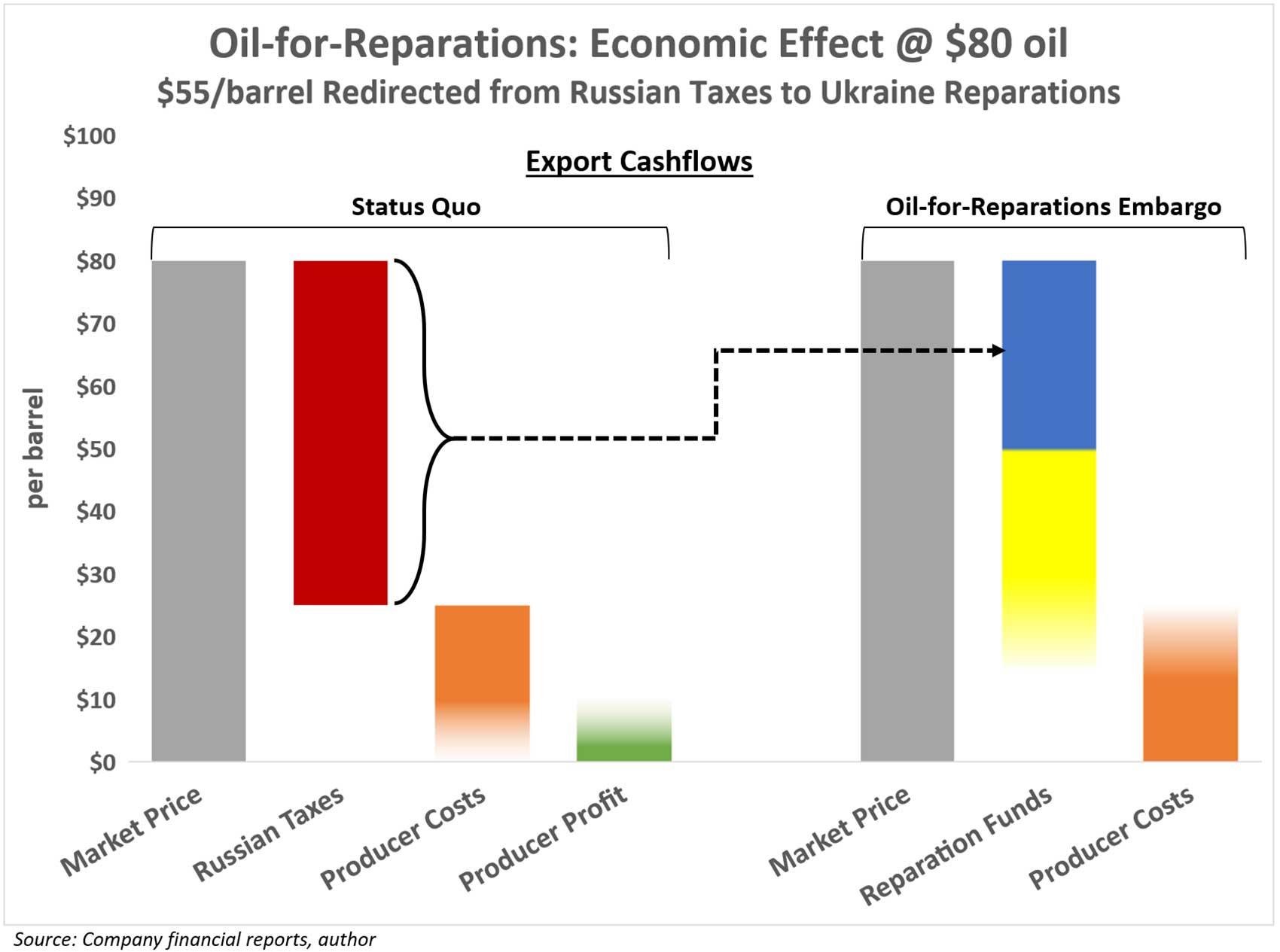

Based on average Russian costs, this would be around $20 -$25 a barrel or roughly a quarter of today’s oil price. The remaining surplus—what would normally flow to the Kremlin as taxes—goes instead to Ukraine for reparations (Figure 3). At today’s prices that would be around $55 a barrel, equal to around a half a billion dollars a day. Accordingly, this framework could be called the “Oil-for-Reparations (OFR) Sanctions.”

Figure 3

This Oil-for-Reparations framework has several advantages: 1) it funds Ukrainian reparations at Russia’s expense, 2) it prevents an oil price shock and 3) it slashes Russian oil tax revenues, with severe consequences for the Russian budget. Its chief drawbacks are 1) some corporate oil export revenues continue to flow back into Russia and 2) it cannot be imposed unilaterally; Russian producers must agree to sell.

This last point—the need for compliant sales by Russia—is a significant uncertainty. As part of the framework, the West must impose secondary sanctions on any non-compliant export sales outside of the sanctions regime. This would make it all the more difficult for Russia to redirect a significant portion of these volumes elsewhere. Russia’s Western volumes would, in effect, become “captive oil.”

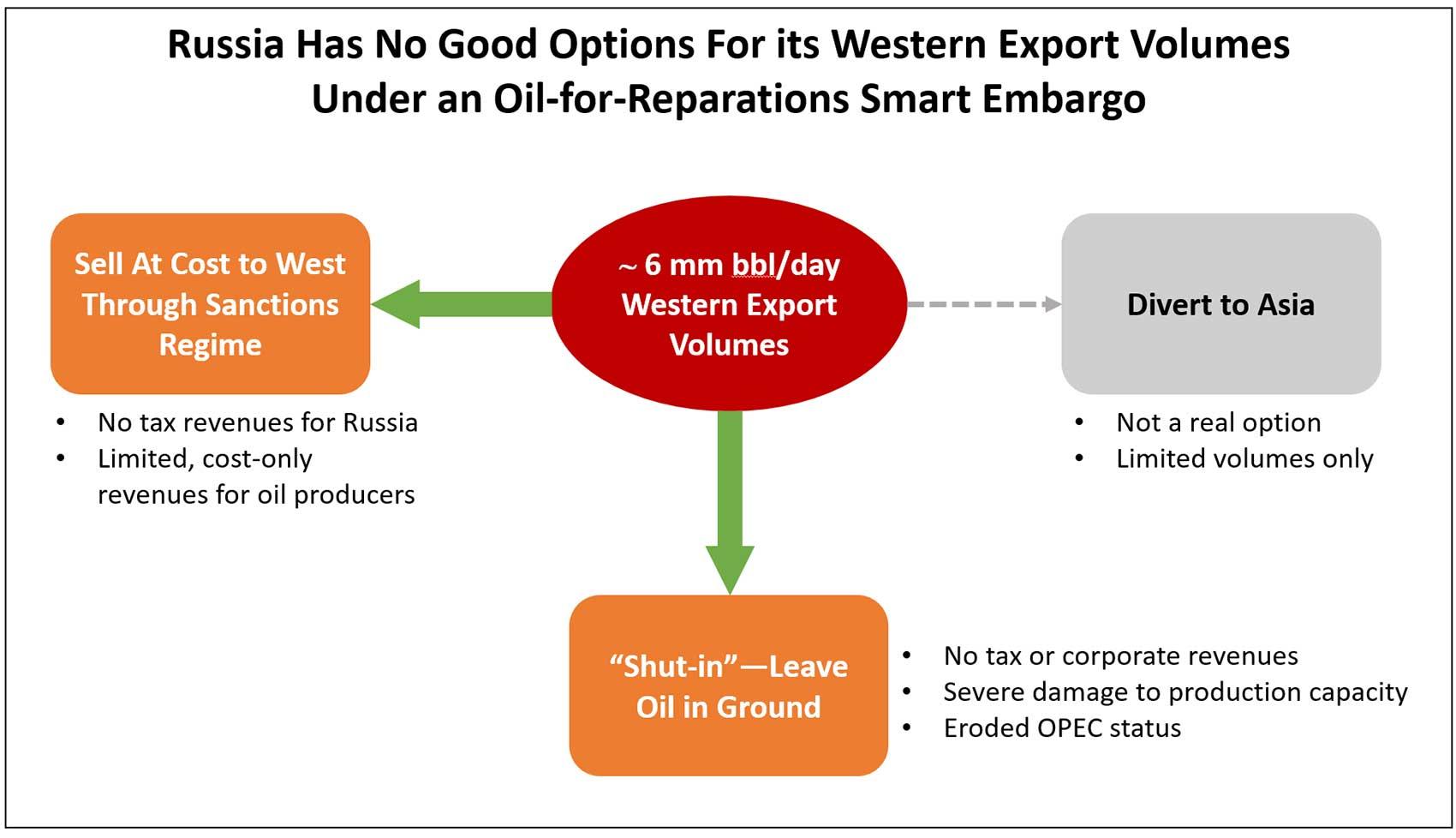

That would present Russia with a stark choice: either agree to export under the sanctions regime, or voluntarily elect to shut in most export oil (Figure 4). While agreeing to sell is clearly in Russia’s economic interest, it’s entirely likely the Kremlin would opt instead—at least initially—to start shutting-in in hopes of roiling global markets and breaking Western resolve. And one cannot assume that Putin will be fully briefed on the catastrophic impact such a shut-in could have on Russia’s oil sector.

Figure 4

Even if Russian opts for a shut-in, there are still significant advantages to including a smart embargo option. For one thing, Russia might decide, instead, to participate—if not immediately, then at some later point. Additionally, having this option goes some way to shifting responsibility for the shut-in—and the resulting supply shock—away from the West and onto Russia. Politically, that shifting of responsibility is valuable. The price spike following a full shut in will be painful for oil consumers everywhere. OPEC, likewise, will not welcome loss of control over prices. The smart embargo strategy shows a good-faith effort by the West to prevent a supply shock. If a supply shock does occur, Russia will have to share the blame, including from erstwhile ally China.

The West should also prepare an expansion of current oil field services sanctions. At present, these are very limited and have little impact on current production. Russia is growing increasingly dependent on Western oil field equipment, services and technology to maintain production levels. The West should prepare to expand these sanctions to ban all Western oil field services in Russia, especially if Russia opts for a self-imposed shut-in.

Read More

Read the complete paper on Navigating Russia.