The summer is about to start, but our trips to new lands, in search of new experiences, views, flavors, and human encounters, are cancelled for most of us due to the pandemic. The Program on Central Asia hopes to make up for this loss by offering you a selection of six travelogues written by curious, intelligent, observant Westerners (four adventurous men and two exceptionally brave women) who visited Central Asia in the second half of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth century.

We asked a diplomat, a scholar, and an author to choose their favorite travelogues for our readers:

Caroline Eden is a writer and critic contributing to The Guardian, Financial Times and The Times Literary Supplement. She is author of the award-winning Samarkand: Recipes and Stories from Central Asia and the Caucasus (2016); Black Sea (2018), the tale of a journey between the great cities of Odessa, Istanbul, and Trabzon; and Red Sands: Reportage and Recipes through Central Asia, from Hinterland to Heartland (forthcoming in 2020).

Erzhan Kazykhanov is Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America. A trained historian, he earned his bachelor’s degree in Oriental studies from St. Petersburg State University and holds a Ph.D. in History from Al-Farabi Kazakh National University.

Edward Lemon is assistant professor of Eurasian affairs at the Daniel Morgan Graduate School in Washington, D.C. His research focuses on security issues in Central Asia. He has conducted extensive fieldwork in Tajikistan, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan. He collects historic travelogues on the Inner Asian region.

Oriental and Western Siberia: A narrative of seven years' explorations and adventures in Siberia, Mongolia, the Kirghis steppes, Chinese Tartary, and part of Central Asia (1858) by Thomas Atkinson

Recommended by Ambassador of Kazakhstan to the United States of America Erzhan Kazykhanov

This book is a based on an incredible journey undertaken by the English architect and artist Thomas Atkinson (1799–1861) to the Kazakh steppes and onward into remote parts of Xinjiang, Mongolia, and Southern Siberia. Between 1847 and 1853 he traveled forty thousand miles, nearly a third of it on horseback. The book provides a vivid account of adventures and misadventures in a frozen and often barren landscape, including numerous close brushes with death from both natural and unnatural causes. It is richly illustrated by Atkinson’s drawings and watercolors.

In 1848 Thomas made a brief trip to Moscow, where he married Lucy Finley. She accompanied him for the rest of the long journey across Eurasia and also penned a remarkable book describing their travels, Recollections of Tartar Steppes and Their Inhabitants (1863). During these travels Lucy gave birth to a son in the town of Kapal at the foot of Djungar Alatau mountains. The couple named him Alatau Tamchiboulac after the local Tamshybulak spring.

Years later, Alatau would move to Hawaii, where he became a member of the House of Representatives for the Republic of Hawaii. He served as Superintendent of Public Instruction for the Territory of Hawaii following its annexation to the United States, and as editor of The Hawaiian Gazette, as well as president of the Hawaiian Star Newspaper Association. What is also fascinating about this story is the fact that the Embassy of Kazakhstan in London was able to find the descendants of Atkinsons who now live in Hawaii and in New Hampshire, United Kingdom, and recreate Thomas and Lucy's journey through the Kazakh steppes in the summer of 2016. Through this beautiful story, we were able to connect generations of Kazakh, American, and British people, as well as show how our world is indeed interconnected and we are all part of significant history. By reading this book, I hope readers will embark on a journey that transcends borders, centuries, and civilizations—and find some new knowledge and understanding in the process.

Merv: A Story of Adventure and Captivity (1883) by Edmond O’Donovan

Recommended by Edward Lemon

Merv: A Story of Adventure and Captivity offers an account of Irish war correspondent Edmond O’Donovan’s time in modern-day Turkmenistan in 1879. A condensed version of the two-volume The Merv Oasis, the book bears witness to the final days of Turkmen independence before Russian rule.

Born in Dublin in 1844, O'Donovan joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood in his teens before joining the Foreign Legion in 1870 and fighting in the Franco-Prussian War. He started writing for The Irish Times in 1866, reporting from Spain and the Balkans before being sent to modern-day Turkmenistan by the Daily News in 1879. After the subjugation of the Khanate of Bukhara in 1868 and Khiva in 1873, the Turkmen tribes were some of the last in Central Asia to resist Russian rule. O’Donovan was given permission to accompany the troops of General Lazarev as he tried to bring the Turkmen under control in 1879. After a few months in camp, O’Donovan abandoned the Russians, heading to Persia. Here he hatched a plan to try and join up with the Turkmen forces. Re-entering Transcaspia, he witnessed the fall of Geok Tepe to General Mikhail Skobelev’s forces in January 1881. The event brought Dostoyevsky to triumphantly declare in his last entry in his diary before dying that “in Europe, we were hangers-on and slaves, whereas we shall go to Asia as masters.”

But this did not signify the total capitulation of the Turkmen people to imperial rule. Merv, under the rule of Makdum Kuli Khan, held out. Khan invited him to visit Merv. Arrested and briefly detained on the road on suspicion of being a Russian spy, O’Donovan proceeded to Merv, where he spent five months. Seen as something of a curiosity, O’Donovan became a regular at the majlis, the council of elders. Eventually, he was officially declared a khan and designated the ambassador of the English queen to the Turkmen people, a title, he explained, he could not accept. O’Donovan is an astute observer of the peoples and cultures of the region, offering glimpses of life in modern-day Turkmenistan in the final years before colonial rule. Three years after O’Donovan left, Merv came under Russian rule.

Through Russian Central Asia (1916) by Stephen Graham

Recommended by Edward Lemon

Essayist and expert on Russia Stephen Graham arrives in Central Asia in 1914, traveling from Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi) and the Kazakh Alai mountains, where he receives news that war has been declared in Europe. His book is one of the last travelogues to focus on Tsarist Central Asia.

Graham first travelled to Russia in 1906. In the ensuing years, he travelled all over the country, reporting for The Times. Sympathetic to the poor, to agricultural laborers, and to tramps, he often travelled on foot covering thousands of miles and publishing his reflections in a series of books including A Vagabond in the Caucasus (1911), A Tramp's Sketches (1912) and With Russian Pilgrims to Jerusalem (1913). Tramping for Graham was like a pilgrimage, allowing one to gain a pure experience and search for the truth. His prose is highly polished, at times reflective, at others amusing.

Arriving at the port of Krasnovodsk, modern-day Turkmenbashi, he travelled along the Trans-Caspian Railway to Bukhara, Samarkand, and Tashkent. Travelling on foot for much of the way, stopping at Kyrgyz yurts, Mennonite and Cossack “pioneer villages”, Graham gets as far as the Kazakh Altai mountains, stopping in Pishpek (Bishkek), Verniy (Almaty), and at a leper colony on the border with China. Graham is a meticulous record keeper, tracking his travel costs; boiling water costs 5 kopeks, and kumys (fermented mare's milk) 10 kopeks. Graham was not a fan of kumys. When told it is like champagne:

“But, to start with, it is white,” said I.

“Oh it’s not the colour; it’s the quality.”

“It is best when it is thick.”

“It’s not a matter of being thick or thin, but in the tingling taste and the exuberance and happiness you feel after it.”

Stephen Graham

Graham’s trip ended in the Altai mountains of northern Kazakhstan, where he learned of the outbreak of war. His next book, Russia and the World, takes up the story at the beginning of the war and takes him across the Russian Empire in its first year at war.

Through Khiva to Golden Samarkand (1925) by Isabella Robertson Christie

Recommended by Caroline Eden

A spirited and sharp-eyed traveller, Isabella “Ella” Christie was born in 1861, close to Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital. In 1910 and 1912, before the start of the First World War, she set off to visit “the heart of Turkestan’, publishing her adventures, Through Khiva to Golden Samarkand, in 1925. First, she travelled from Moscow to the Aral Sea and to Kokand; then, on her second trip, she ventured from Constantinople across the Caspian Sea to the Fergana Valley and Tashkent.

My reasons for making the journey were twofold, first, the extreme desire to see for myself what lay on that comparatively bare spot on the map east of the Caspian Sea ... and secondly, the lure of those magic names, Bokhara and Samarkand.

Isabella Robertson Christie

Before departing, the Foreign Office issued her a personal warning. Should she contract plague in Central Asia, they advised, she ought to “Hang a red cloth over the window.’ But Christie knew such government advice was questionable. “No thought was given as to where red cloth was to be obtained, if there would be any windows over which to hang it.” Christie simply made a note of this guidance, and went anyway.

Samarkand, in particular, did not disappoint. Christie was spellbound by the great tiled buildings and wrote of Tamerlane’s final resting place, the Gur-e-Amir: “I can never forget the sight of that fluted blue dome rising far above the delicate spring green.” She found it “Amazing, considering that he lived as far back as the fourteenth century, that so much remains of those architectural adornments added by him to Samarkand, which he made his capital.” One-eyed and with crippled limbs, Tamerlane is believed by some historians to have wanted to beautify his surroundings as he was not a handsome man, refusing to ever look in a mirror, even, while others say it was simply his way of venerating God.

What sets Ella Christie’s work apart from better-remembered British writers of this region, such as Peter Hopkirk and Sir Fitzroy Maclean, are her commonplace observations and her motivation.

Rather than setting out to spy, break records, or gain victories, she took great pleasure in observing and noting the domestic and commonplace—cooking, clothing, and workshops—in considerable detail; and clearly with much joy. But that’s not to say she wasn’t tenacious. On her journeys, she described being pinned down by fear in her carriage out on the steppe by thoughts of a black spider called a karakurt, capable of killing a camel in three hours; and eating eggs cooked by spirit lamp. She also notes ice cream sellers at various places, including at Kokand, in present-day Uzbekistan. Cream was not an ingredient; instead this treat was made simply of frozen ice and raisin syrup. In Samarkand, she watches as a vendor goes about making his ices by pouring a ladle of the syrup onto the ice over a brass platter, then stirring the mixture with a wooden spoon. She also writes in animated detail about plov, “which is rice cooked in a certain manner with mutton fat, to which is added small bits of the meat, shreds of carrots, quince, and raisins, and is also an acceptable dish to Europeans.” Some historians believe she was the first British woman to visit Khiva, but it is her vivid descriptions of her journeys that matter so much and have such value, far more than any accolade.

Alone in the Forbidden Land (1939) by Gustav Krist

Recommended by Edward Lemon

Austrian carpet trader Gustav Krist’s account of early Soviet Central Asia, Alone Through the Forbidden Land, provides fascinating insights into a society undergoing a period of profound change. First published in English in 1939, the book documents Krist’s journey through Central Asia between 1924 and 1925.

Captured by the Russians in 1914, Krist was one of some 40,000 Austro-Hungarian who spent the rest of the war imprisoned in camps in Central Asia. He stayed in the region for six years, acting as an interpreter and serving the Emir of Bukhara during his ill-fated attempt to resist Soviet rule in 1920.

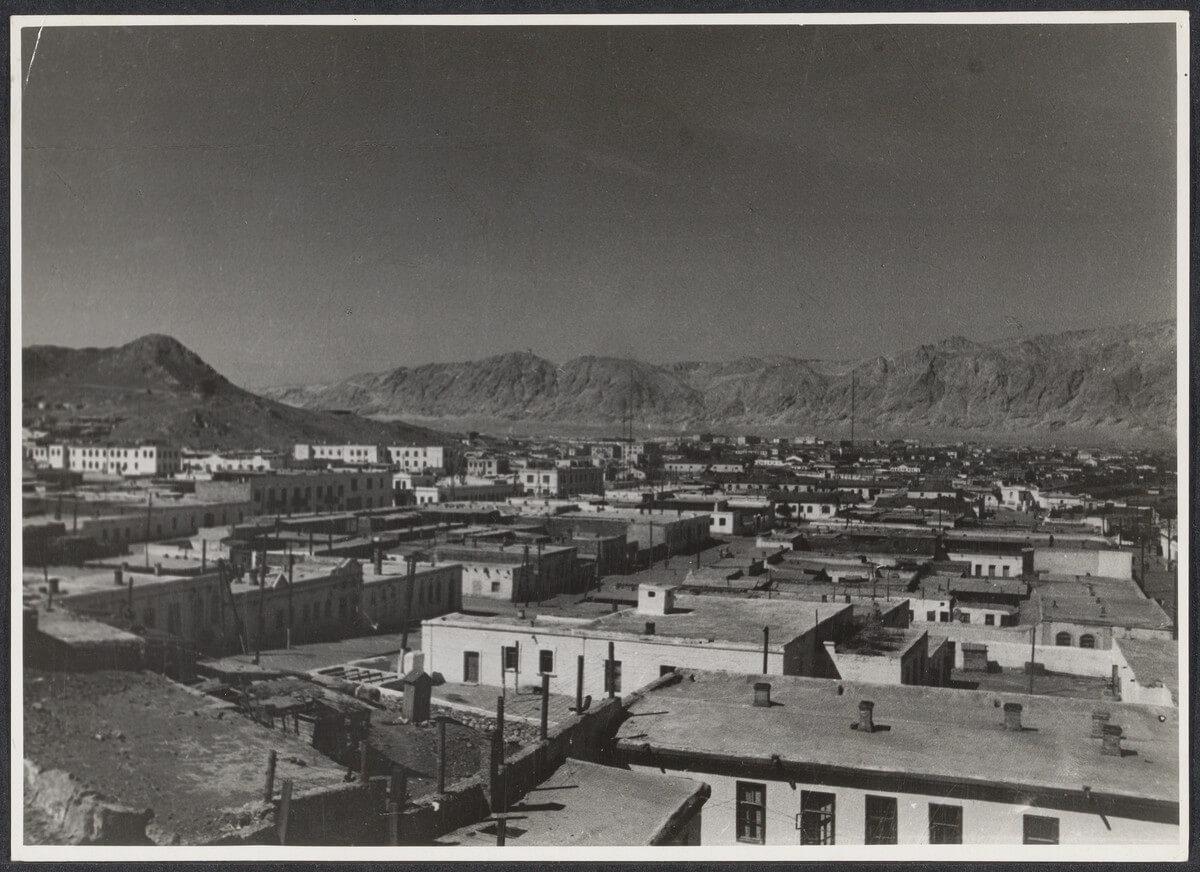

A chance meeting in Persia with a group of Turkmen rug traders in 1924 brought him back to the region. Travelling in disguise as a geologist, Krist in his account focuses largely on the less frequently visited Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Krist describes living with the nomadic Kyrgyz in the Pamir Alai mountains, Dushanbe, the newly established capital of the Tajik ASSR, and the field where former Ottoman General Enver Pasha met his end in 1922.

Krist’s remarkable account captures Central Asia at a time of transition; although the Soviets nominally controlled the region, they were yet to fully consolidate their power. The picture that Krist constructs is one of limited Soviet power and local resistance.

He bore witness to the final year in which nomads could freely travel to the summer pastures:

To an enormous distance I could see camel train after camel train; the entire horde was on trek, flying from officials of the Soviet . . . hot tears filled my eyes, although I little suspected at the time that I had been the witness of the last march of the free Kirghiz.

Gustav Krist

One year later the Soviet authorities rounded up and collectivized the nomads of Central Asia. More than a million Uzbeks, Turcomans, Kazakhs, and other tribesmen died as a result.

An astute observer, Krist documents the lives of the people he meets and how they are being affected by the new political system. In the Uzbek town of Kerki, he meets Madame Kulaeva. A former slave girl, she now heads the local Soviet. She symbolizes the new “freedom” that women enjoy under Soviet rule. Nevertheless, such “emancipated women” remain the exception rather than the rule.

Krist documents the limits of Soviet secularization. Religion retains a pivotal role in the lives of most Central Asians at this time. He describes how women in Gharm were not permitted to leave their homes and all wore chimat (horse-hair veil). For Krist, the wearing of the veil symbolised the local population’s resistance to Soviet modernisation. Indeed, most Muslims continued to keep the fast during Ramadan. According to Krist, “Communist teaching has been powerless to abolish it. The authorities even close the Government offices during the fast and only the military can afford to ignore it.” Krist’s account offers an invaluable insight into early Soviet Central Asia, a time of transition, upheaval, and destruction.

South to Samarkand (1937) by Ethel Mannin

Recommended by Edward Lemon

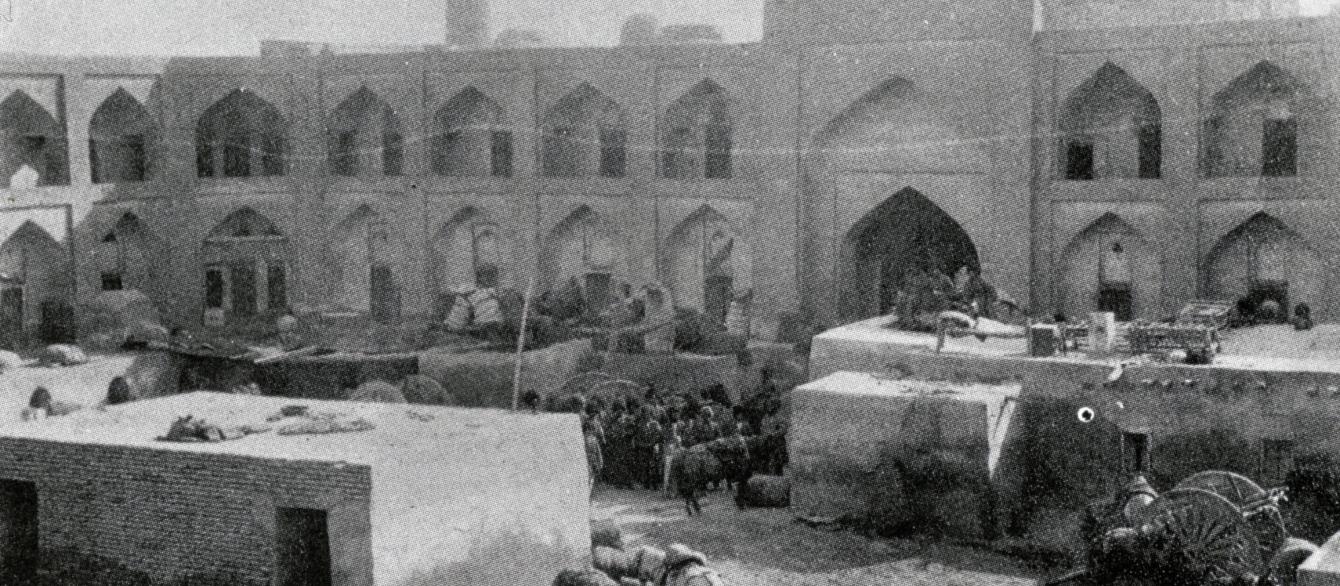

Shah-i Zinda Complex, Samarkand, Samarqand Viloyati, Uzbekistan.

Ethel Mannin, a British feminist, anarchist, and anti-imperialist who had a well-publicized affair with Bertrand Russell, travelled to Central Asia in 1936, intrigued to see how Communism was changing life there. She left disillusioned with Stalinism.

The first half of the book takes us from Leningrad to Kiev and then around the Black Sea coast to the Caucasus. From Baku, Mannin and her travel companion, Donia Nachsen, with whom she fell out over her rejection of Stalinism, had an uncomfortable crossing in “fourth class” across the Caspian to reach the Turkmen SSR.

Mannin traveled from the Turkmen SSR to reach her destination: Samarkand. Enchanted by the city’s spectacular architecture and rich history, she is confronted with a changing city in the grips of Soviet modernization. Soviet Samarkand does not quite meet Mannin’s preconceived Orientialist notions of the Silk Road city. Having left Samarkand, she arrived in Tashkent on November 7, the anniversary of the Russian Revolution, recounting the festivities. From here, they returned to Moscow, where Mannin was relieved to return to a “civilized” city where she could go to the ballet or a dinner party.

Mannin did not shy away from criticizing the Soviet Union, her tone often caustic. Mannin was skeptical of the costs of the “progress” being made under Soviet rule, in particular the restrictions on freedom and traditional ways of life. “Stalinism is impatient of the high glory and is intent on Europeanising Asian Russia,” she wrote. “It is anti-social to merely to sit in the sun and enjoy life, or to roam the great plains or deserts of Russia with horses and herds.” A clearly frustrated Mannin described the food shortages, cumbersome bureaucracy, and endless document checks. “A mechanised civilisation is to be Asia’s heritage from Stalinism,” she concluded. “And a mechanised civilization means tanks as well as tractors, poison gas as well as antiseptics. It means an existence of ruthless efficiency and end of idling in the sun. It means Stakhanovism and the living Robot.” For Mannin, Soviet rule was colonial, imposing outside ideas and destroying local cultural traditions. She ended the book by quoting Edgar Allan Poe’s “Raven,” stating “Never more”; she never returned to the Soviet Union.

In Cities of Turkmenia.